Fear of scientists “playing god” is at the centre of many a plot line in science fiction stories. Perhaps the latest popular iteration of the story we all love is Jurassic World (2015), a film I find interesting only for the tribute it paid to the original Michael Crichton novel and movie Jurassic Park.

Full op-ed from h+ Magazine on 7 October 2015 http://hplusmagazine.com/2015/10/07/opinion-synthetic-biology-the-true-savior-of-mankind/

In Jurassic Park, a novel devoted to the scare of genetic engineering when biotech was new in the 1990s, the character of John Hammond says:

In Jurassic Park, a novel devoted to the scare of genetic engineering when biotech was new in the 1990s, the character of John Hammond says:

“Would you make products to help mankind, to fight illness and disease? Dear me, no. That’s a terrible idea. A very poor use of new technology. Personally, I would never help mankind.”

What the character is referring to is the lack of profit in actually curing diseases and solving human needs, and the controversy courted just by trying to get involved in such development. The goal to eradicate poverty or close the wealth gap between rich and poor nations offers no incentive for a commercial company.

Instead, businesses occupy themselves with creating entertainment, glamour products and perfume, new pets, and other superfluities that biotech can inevitably offer. This way, the companies escape not only moral chastisement for failing to share their technology adequately or make it freely available, but they can also attach whatever price tag they want without fear of controversy.

It is difficult for a well-meaning scientist or engineer to push society towards greater freedom and equality in a single country. It is even harder for such a professional to effect a great change over the whole world or improve the human condition the way transhumanists, for example, have intended.

Although discovery and invention continue to stun us all on an almost daily basis, such things do not happen as quickly or in as utilitarian a way as they should. And this lack of progress is deliberate. As the agenda is driven by businessmen who adhere to the times they live in, driven more by the desire for wealth and status than helping mankind, the goal of endless profit directly blocks the path to abolish scarcity, illness and death.

Today, J. Craig Venter’s great discoveries of how to sequence or synthesize entire genomes of living biological specimens in the field of synthetic biology (synthbio) represent a greater power than the hydrogen bomb. It is a power we must embrace. In my opinion, these discoveries are certainly more capable of transforming civilization and the globe for the better. In Life at the Speed of Light(2013), that is essentially Venter’s own thesis.

Today, J. Craig Venter’s great discoveries of how to sequence or synthesize entire genomes of living biological specimens in the field of synthetic biology (synthbio) represent a greater power than the hydrogen bomb. It is a power we must embrace. In my opinion, these discoveries are certainly more capable of transforming civilization and the globe for the better. In Life at the Speed of Light(2013), that is essentially Venter’s own thesis.

And contrary to science fiction films, the only threat from biotech is that humans will not adequately and quickly use it. Business leaders are far more interested in profiting from people’s desire for petty products, entertainment and glamour than curing cancer or creating unlimited resources to feed civilization. But who can blame them? It is far too risky for someone in their position to commit to philanthropy than to stay a step ahead of their competitors.

Even businessmen who later go into philanthropy do very little other than court attention in the press and polish the progressive image of the company. Of course, transitory deeds like giving food or clean water to Africans will never actually count as developing civilization and improving life on Earth, when there are far greater actions that can be taken instead.

It is conspicuous that so little has been done to develop the industrial might of poor countries, where schoolchildren must still live and study without even a roof over their heads. For all the unimaginable destruction that our governments and their corporate sponsors unleash on poor countries with bombs or sanctions when they are deemed to be threatening, we see almost no good being done with the same scientific muscle in poor countries. Philanthropists are friendly to the cause of handing out food or money to a few hungry people, but say nothing of giving the world’s poor the ability to possess their own natural resources and their own industries.

Like our bodies, our planet is no longer a sufficient vehicle for human dreams and aspirations. The biology of the planet is too inefficient to support the current growth of the human population. We face the prospect of eventually perishing as a species if we cannot repair our species’ oft-omitted disagreements with nature over issues of sustainability, congenital illness and our refusal to submit to the cruelties of natural selection from which we evolved.

Once we recognize that the current species are flawed, we will see that only by designing and introducing new species can suffering, poverty and the depletion of natural resources be stopped. Once we look at this option, we find already a perfect and ultimately moral solution to the threats of climate change, disease, overpopulation and the terrible scarcity giving rise to endless injustice and retaliatory terrorism.

The perfect solution could only be brought to the world by a heroic worker in the fields of biotech and synthetic biology. Indeed, this revolution may already be possible today, but fear is sadly holding back the one who could make it happen.

Someone who believes in changing the human animal with technology must believe in eradicating poverty, sickness and injustice with technology. For all our talk of equality and human rights in our rhetoric, the West seems determined to prevent poorer countries from possessing their own natural resources. A right guaranteed by the principles of modernization and industrialization, which appears to have been forgotten. Instead, we prefer to watch them being nursed by the richer countries’ monopolies, technology, and workers who are there cultivating, extracting, refining, or buying all their resources for them.

So, quite contrary to the promises of modernity, we have replaced the ideal of the industrialization of poor states with instead the vision of refugee camps, crude water wells, and food aid delivered by humanitarian workers to provide only temporary relief. In place of a model of development that was altruistic and morally correct, we instead glorify the image of non-Westerners as primitives who are impossible to help yet still we try.

The world’s poor have become not the focus of attention aimed at helping humanity, but props for philanthropists to make themselves look noble while doing nothing to truly help them. What we should turn to is not a return to the failed UN development agendas of the 1970s, which were flawed, but a new model entirely, and driven by people instead of governments and UN agencies.

It is high time that we act to help mankind altruistically, rather than a select few customers. The engineers and scientists of the world need to abandon the search for profit, if only for a moment. We should call on them to turn their extraordinary talent to the absolute good of abolishing poverty and scarcity. If they do not do this, we will talk about direct action to break free the scientific gifts they refused to share.

We live in courageous times. These are times of whistle-blowers, lone activists for the truth, and lone scientist-entrepreneurs who must be praised even if our profit-driven culture stifles their great works. And although we live in courageous times, we seem not yet brave enough to take real action to overcome the human disaster.

###

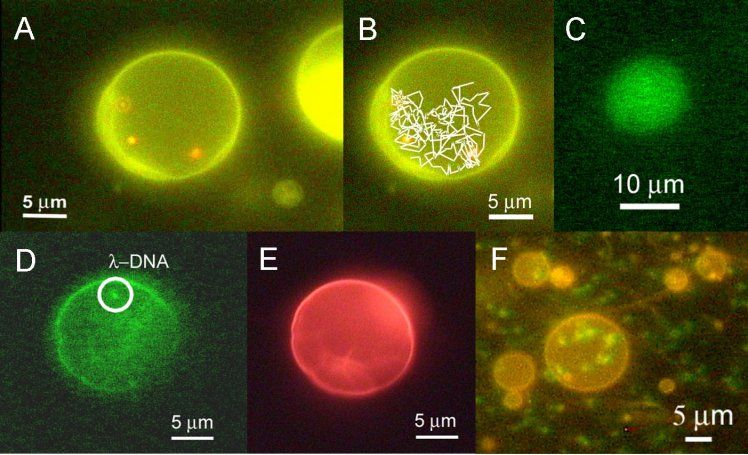

Synthetic biology image from https://www.equipes.lps.u-psud.fr/TRESSET/research8.html

(A) Enclosure of three red-fluorescent 200-nm spheres inside a “giant” liposome labeled with DiO. A wideband ultraviolet excitation filter was used for the simultaneous observation of these two differently stained species. Images were digitally postprocessed to balance the colors and to adjust their brightness at an equal level. (B) Trajectories of the particles. They were free to move but did not pass through the membrane. © GFP entrapped by a “giant” liposome. To get rid of noncaptured proteins, the solution was filtered by dialysis in such a way that the fluorescence background level became negligible with respect to the liposome interior. (D) Fluorescence photographs of λ-DNA-loaded liposome. λ-DNA was stained with SYBR Green, while DiI (red emission) was incorporated to liposome membrane. Liposome was observed through a narrow-band blue excitation filter (suitable for SYBR Green). (E) Same as previously with a wideband green excitation filter (suitable for DiI). Because of a low fluorescence response, part D was digitally enhanced in terms of brightness and contrast. In comparison, part E was darkened to present a level similar to part D. These pictures were taken at an interval of ~1 s, just the time to switch the filters. (E) Fluorescence picture of λ-DNA-loaded liposomes. Green dots stand for λ-DNA molecules, and lipids are labeled in red. A wideband blue excitation filter was used for this bicolor imaging, and a high-sensitivity color CCD camera captured it. [Anal. Chem. 77 (2005) 2795]

In Jurassic Park, a novel devoted to the scare of genetic engineering when biotech was new in the 1990s, the character of John Hammond says:

In Jurassic Park, a novel devoted to the scare of genetic engineering when biotech was new in the 1990s, the character of John Hammond says: Today, J. Craig Venter’s great discoveries of how to sequence or synthesize entire genomes of living biological specimens in the field of synthetic biology (synthbio) represent a greater power than the hydrogen bomb. It is a power we must embrace. In my opinion, these discoveries are certainly more capable of transforming civilization and the globe for the better. In

Today, J. Craig Venter’s great discoveries of how to sequence or synthesize entire genomes of living biological specimens in the field of synthetic biology (synthbio) represent a greater power than the hydrogen bomb. It is a power we must embrace. In my opinion, these discoveries are certainly more capable of transforming civilization and the globe for the better. In