Nvidia has built its very own supercomputer, for some reason.

TOKYO (AFP) — Japan’s Fugaku supercomputer, built with government backing and used in the fight against coronavirus, is now ranked as the world’s fastest, its developers announced Monday (June 22).

It snatched the top spot on the Top500, a site that has tracked the evolution of computer processing power for more than two decades, said the Riken scientific research centre.

The list is produced twice a year and rates supercomputers based on speed in a benchmark test set by experts from Germany and the US.

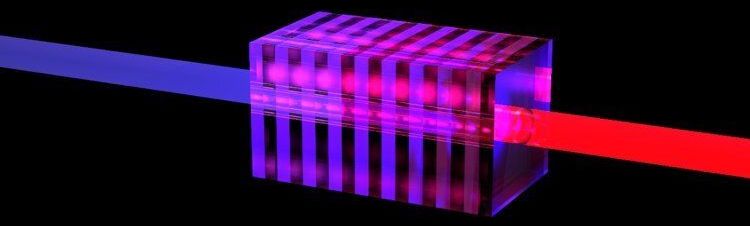

Fifty is a critical number for quantum computers capable of solving problems that classic supercomputers cannot solve. Proving quantum supremacy requires at least 50 qubits. For quantum computers working with light, it is equally necessary to have at least 50 photons. And what’s more, these photons have to be perfect, or else they will worsen their own quantum capabilities. It is this perfection that makes it hard to realize. Not impossible, however, which scientists of the University of Twente have demonstrated by proposing modifications of the crystal structure inside existing light sources. Their findings are published in Physical Review A.

Photons are promising in the world of quantum computing, with its demands of entanglement, superposition and interference. These are properties of qubits, as well. They enable building a computer that operates in a way that is entirely different from making calculations with standard bits that represent ones and zeroes. For many years now, researchers have predicted quantum computers able to solve very complex problems, like instantly calculating all vibrations in a complex molecule.

The first proof of quantum supremacy is already there, accomplished with superconducting qubits and on very complicated theoretical problems. About 50 quantum building blocks are needed as a minimum, whether they are in the form of photons or qubits. Using photons may have advantages over qubits: They can operate at room temperatures and they are more stable. There is one important condition: the photons have to be perfect in order to get to the critical number of 50. In their new paper, UT scientists have now demonstrated that this is feasible.

The supercomputer Fugaku – jointly developed by RIKEN and Fujitsu, based on Arm technology – has taken first place on Top500, a ranking of the world’s fastest supercomputers.

It swept other rankings too – claiming the top spot on HPCG, a ranking of supercomputers running real-world applications; and HPL-AI, which ranks supercomputers based on their performance in artificial intelligence applications; and Graph 500, which ranks systems based on data-intensive loads.

This is the first time in history that the same supercomputer has achieved number one on Top500, HPCG, and Graph500 simultaneously. The awards were announced today at the ISC High Performance 2020 Digital, an international high-performance computing conference.

MIT engineers have designed a “brain-on-a-chip,” smaller than a piece of confetti, that is made from tens of thousands of artificial brain synapses known as memristors — silicon-based components that mimic the information-transmitting synapses in the human brain.

The researchers borrowed from principles of metallurgy to fabricate each memristor from alloys of silver and copper, along with silicon. When they ran the chip through several visual tasks, the chip was able to “remember” stored images and reproduce them many times over, in versions that were crisper and cleaner compared with existing memristor designs made with unalloyed elements.

Their results, published on June 8, 2020, in the journal Nature Nanotechnology, demonstrate a promising new memristor design for neuromorphic devices — electronics that are based on a new type of circuit that processes information in a way that mimics the brain’s neural architecture. Such brain-inspired circuits could be built into small, portable devices, and would carry out complex computational tasks that only today’s supercomputers can handle.

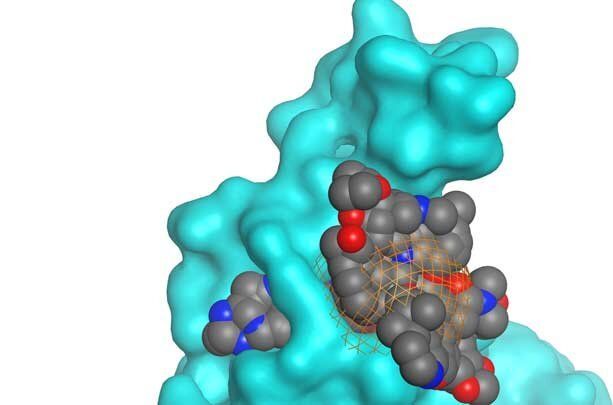

The Baudry Lab at The University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH) has identified 125 naturally occurring compounds that have a computational potential for efficacy against the COVID-19 virus from the first batch of 50,000 rapidly assessed by a supercomputer.

It’s the first time a supercomputer has been used to assess the treatment efficacy of naturally occurring compounds against the proteins made by COVID-19. Located in UAH’s Shelby Center for Science and Technology, the lab is searching for potential precursors to drugs that will help combat the global pandemic using the Hewlett Packard Enterprise (HPE) Cray Sentinel supercomputer.

The UAH team is led by molecular biophysicist Dr. Jerome Baudry (pronounced Bō-dre), the Mrs. Pei-Ling Chan Chair in the Department of Biological Sciences. Dr. Baudry is video blogging about his COVID-19 research journey using HPE’s Cray Sentinel system. His research is in collaboration with the National Center for Natural Products Research at the University of Mississippi School of Pharmacy and HPE.

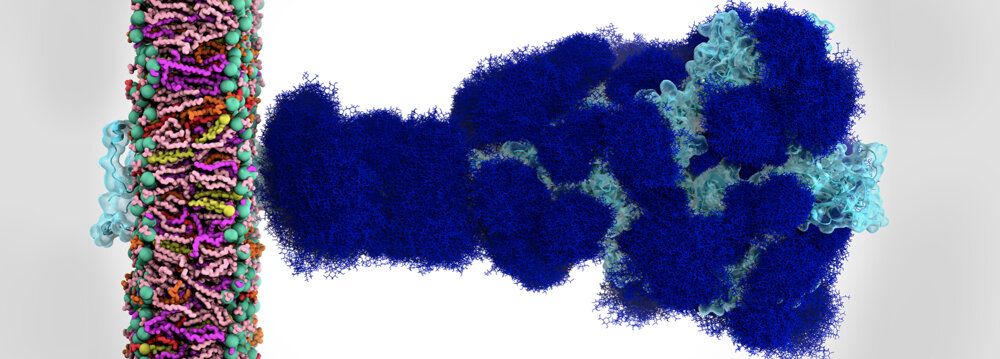

They say you can’t judge a book by its cover. But the human immune system does just that when it comes to finding and attacking harmful microbes such as the coronavirus. It relies on being able to recognize foreign intruders and generate antibodies to destroy them. Unfortunately, the coronavirus uses a sugary coating of molecules called glycans to camouflage itself as harmless from the defending antibodies.

Simulations on the National Science Foundation (NSF)-funded Frontera supercomputer at the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC) have revealed the atomic makeup of the coronavirus’s sugary shield. What’s more, simulation and modeling show that glycans also prime the coronavirus for infection by changing the shape of its spike protein. Scientists hope this basic research will add to the arsenal of knowledge needed to defeat the COVID-19 virus.

Sugar-like molecules called glycans coat each of the 65-odd spike proteins that adorn the coronavirus. Glycans account for about 40 percent of the spike protein by weight. The spike proteins are critical to cell infection because they lock onto the cell surface, giving the virus entry into the cell.

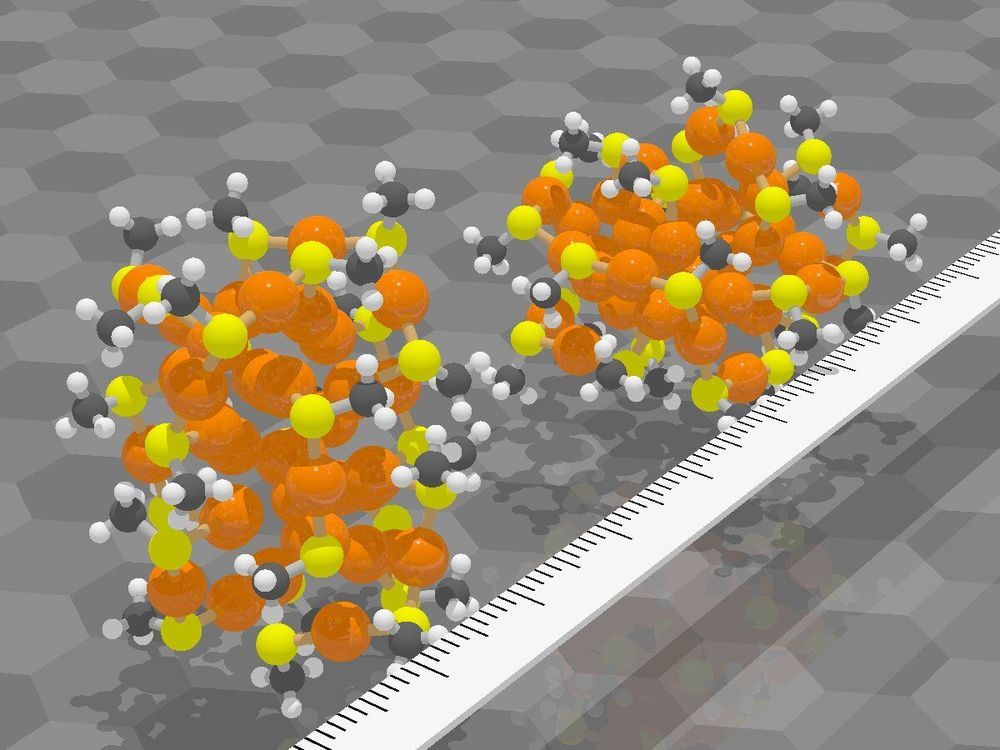

Researchers at the Nanoscience Center and at the Faculty of Information Technology at the University of Jyväskylä in Finland have demonstrated that new distance-based machine learning methods developed at the University of Jyväskylä are capable of predicting structures and atomic dynamics of nanoparticles reliably. The new methods are significantly faster than traditional simulation methods used for nanoparticle research and will facilitate more efficient explorations of particle-particle reactions and particles’ functionality in their environment. The study was published in a Special Issue devoted to machine learning in the Journal of Physical Chemistry on May 15, 2020.

The new methods were applied to ligand-stabilized metal nanoparticles, which have been long studied at the Nanoscience Center at the University of Jyväskylä. Last year, the researchers published a method that is able to successfully predict binding sites of the stabilizing ligand molecules on the nanoparticle surface. Now, a new tool was created that can reliably predict potential energy based on the atomic structure of the particle, without the need to use numerically heavy electronic structure computations. The tool facilitates Monte Carlo simulations of the atom dynamics of the particles at elevated temperatures.

Potential energy of a system is a fundamental quantity in computational nanoscience, since it allows for quantitative evaluations of system’s stability, rates of chemical reactions and strengths of interatomic bonds. Ligand-stabilized metal nanoparticles have many types of interatomic bonds of varying chemical strength, and traditionally the energy evaluations have been done by using the so-called density functional theory (DFT) that often results in numerically heavy computations requiring the use of supercomputers. This has precluded efficient simulations to understand nanoparticles’ functionalities, e.g., as catalysts, or interactions with biological objects such as proteins, viruses, or DNA. Machine learning methods, once trained to model the systems reliably, can speed up the simulations by several orders of magnitude.

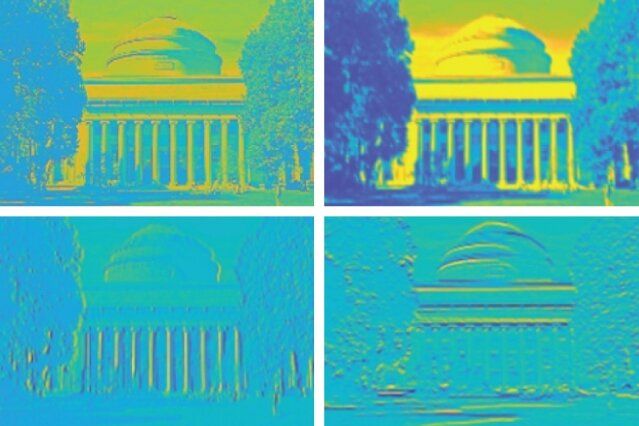

MIT engineers have designed a “brain-on-a-chip,” smaller than a piece of confetti, that is made from tens of thousands of artificial brain synapses known as memristors—silicon-based components that mimic the information-transmitting synapses in the human brain.

The researchers borrowed from principles of metallurgy to fabricate each memristor from alloys of silver and copper, along with silicon. When they ran the chip through several visual tasks, the chip was able to “remember” stored images and reproduce them many times over, in versions that were crisper and cleaner compared with existing memristor designs made with unalloyed elements.

Their results, published today in the journal Nature Nanotechnology, demonstrate a promising new memristor design for neuromorphic devices—electronics that are based on a new type of circuit that processes information in a way that mimics the brain’s neural architecture. Such brain-inspired circuits could be built into small, portable devices, and would carry out complex computational tasks that only today’s supercomputers can handle.