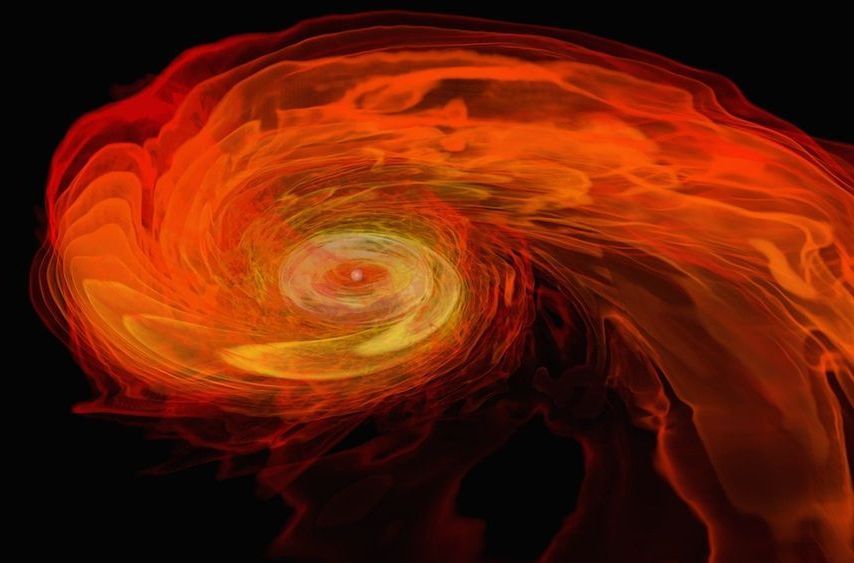

In Jules Verne’s famous classic 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, the iconic submarine Nautilus disappears into the Moskenstraumen, a massive whirlpool off the coast of Norway. In space, stars spiral around black holes; on Earth, swirling cyclones, tornadoes and dust devils rip across the land.

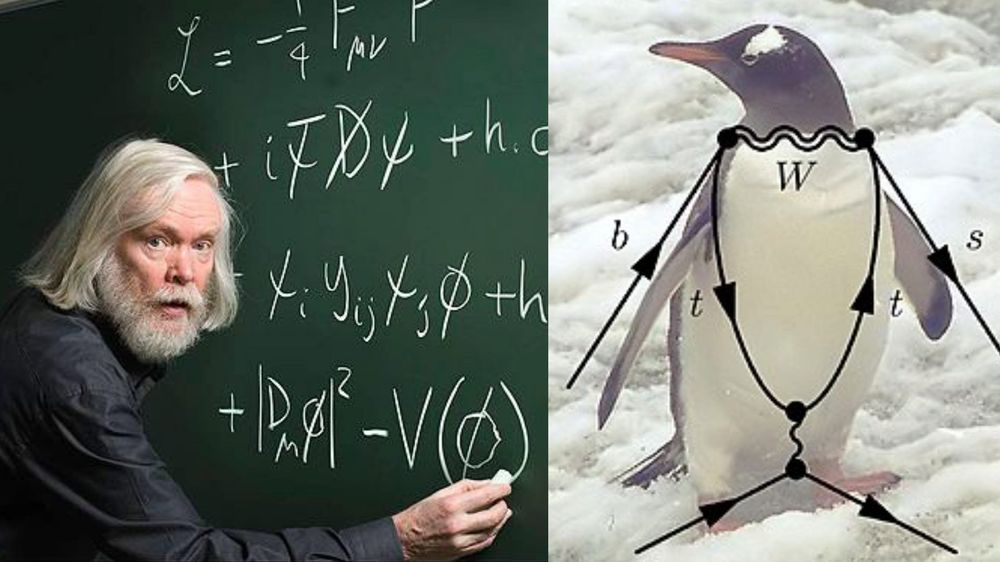

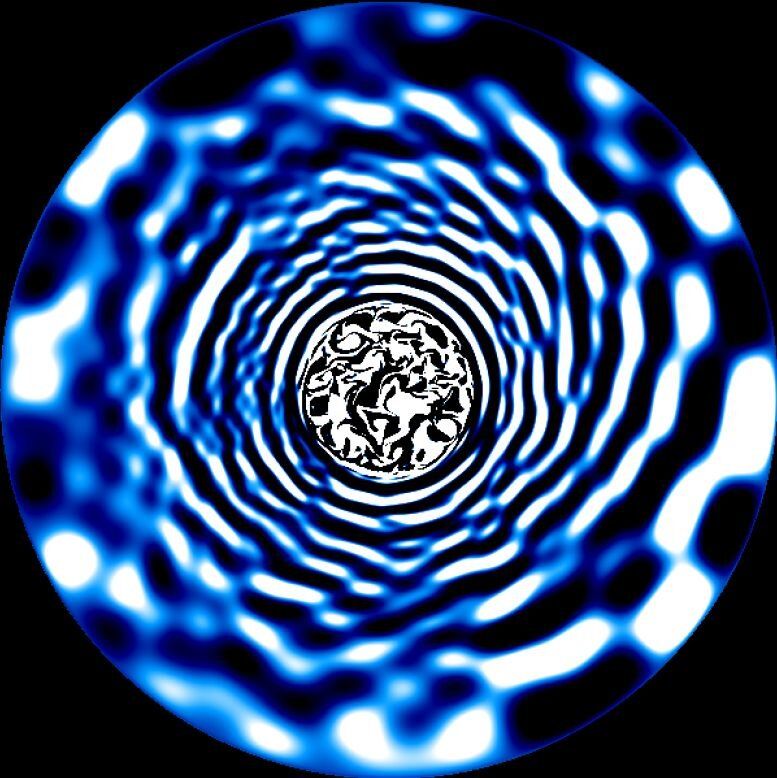

All these phenomena have a vortex shape, which is commonly found in nature, from galaxies to milk stirred into coffee. In the subatomic world, a stream of elementary particles or energy will spiral around a fixed axis like the tip of a corkscrew. When particles move like this, they form what we call “vortex beams.” These beams imply that the particle has a well-defined orbital angular momentum, which describes the rotation of a particle around a fixed point.

Thus, vortex beams can give us new ways of interacting with matter, e.g. enhanced sensitivity to magnetic fields in sensors, or generating new absorption channels for the interaction between radiation and tissue in medical treatments (e.g. radiotherapy). But vortex beams also enable new channels in basic interactions among elementary particles, promising new insights into the inner structure of particles such as neutrons, protons or ions.

Read more