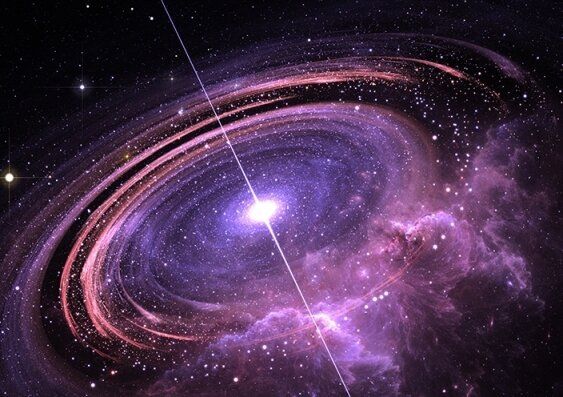

Scientists have found evidence that a fundamental physical constant used to measure electromagnetism between charged particles can in fact be rather in constant, according to measurements taken from a quasar some 13 billion light-years away.

Electromagnetism is one of the four fundamental forces that knit everything in our Universe together, alongside gravity, weak nuclear force, and strong nuclear force. The strength of electromagnetic interaction between elementary particles is calculated with the help of what’s known as the fine-structure constant.

However, the new readings – taken together with other readings from separate studies – point to tiny variations in this constant, which could have huge implications for how we understand everything around us.

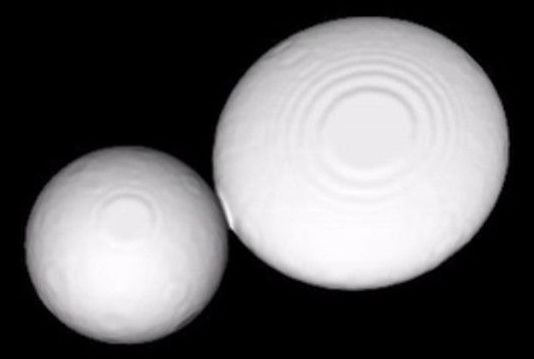

Evgeni Grishin (Credit: Courtesy of The Technion)

Evgeni Grishin (Credit: Courtesy of The Technion)