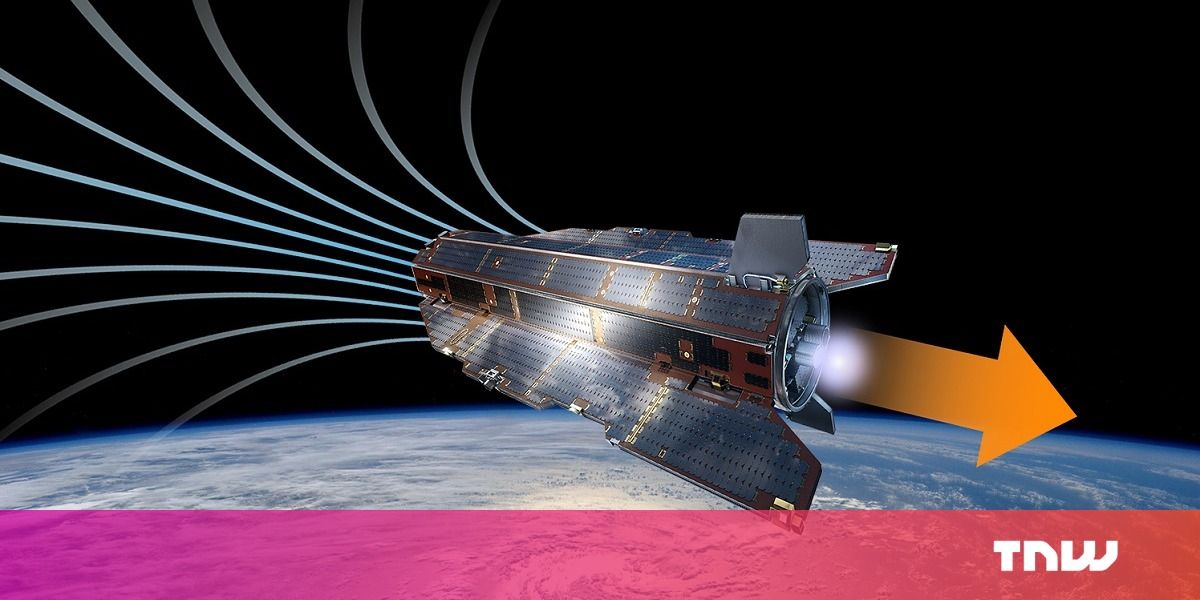

Electric thruster sucks in the scarce air molecules at the top of the Earth’s atmosphere, using them as propellant to fight drag.

Electric thruster sucks in the scarce air molecules at the top of the Earth’s atmosphere, using them as propellant to fight drag.

The European Space Agency created the world’s first thruster which allows satellites to remain in orbit for years longer than they currently do. The secret? The thruster runs on particles of air in the atmosphere.

Others have tried to improve the staying power of satellites before, but most are still limited by the amount of fuel they can carry. The new ion thruster “breathes” the rare air particles in the top of the atmosphere, allowing the satellites to remain without immediate need for refueling.

The thruster was developed by an ESA team and built by SITAEL, a private company in Italy. The air particles bounce away from satellites normally, but the thruster collects them and gives them an electric charge, after which they are ejected to provide thrust that counteracts atmospheric drag.

That’s not a lot to you. If your watch is off by 13.7 microseconds, you’ll make it to your important meeting just fine. But it wasn’t so nice for the first-responders in Arizona, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, and Louisiana, whose GPS devices wouldn’t lock with satellites. Nor for the FAA ground transceivers that got fault reports. Nor the Spanish digital TV networks that had receiver issues. Nor the BBC digital radio listeners, whose British broadcast got disrupted. It caused about 12 hours of problems—none too huge, all annoying. But it was a solid case study for what can happen when GPS messes up.

The 24 satellites that keep GPS services running in the US aren’t especially secure; they’re vulnerable to screw-ups, or attacks of the cyber or corporeal kind. And as more countries get closer to having their own fully functional GPS networks, the threat to our own increases. Plus, GPS satellites don’t just enable location and navigation services: They also give ultra-accurate timing measurements to utility grid operators, stock exchanges, data centers, and cell networks. To mess them up is to mess those up. So private companies and the military are coming to terms with the consequences of a malfunction—and they’re working on backups.

The 2016 event was an accidental glitch with an easily identifiable cause—an oops. Harder to deal with are the gotchas. Jamming and spoofing, on a small scale, are both pretty cheap and easy. You can find YouTube videos of mischievous boys jamming drones, and when Pokemon GO users wanted to stay in their parents’ basements, they sent their own phones fake signals saying they were at the Paris mall. Which means countries, and organized hacking groups, definitely can mess with things on a larger scale. Someone can jam a GPS signal, blocking, say, a ship from receiving information from satellites. Or they can spoof a signal, sending a broadcast that looks like a legit hello from a GPS satellite but is actually a haha from the hacker next-door.

A powerful new weather satellite launched today (March 1) from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida, heading toward a perch above the eastern Pacific Ocean to monitor extreme weather as it develops.

The satellite, called GOES-S (Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite-S), lifted off on ULA’s Atlas V rocket at 5:02 p.m. EST (2202 GMT).

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) will operate GOES-S in partnership with NASA. The Lockheed Martin-built satellite will join GOES-East, currently in orbit, to provide a broad, high-definition view of weather on Earth. It is the second in a series of four advanced weather satellites that will reside in geostationary orbit — hanging in place over one spot on Earth as they orbit and the world turns. [GOES-S: NOAA’s Next-Gen Weather Satellite in Photos].

When SpaceX launched the world’s biggest rocket ship on Feb. 6, that kind of seemed like a big deal — but not everyone is impressed.

Previewing the SpaceX Falcon Heavy launch, The Wall Street Journal seemed perplexed. Yes, the Falcon Heavy is big, admitted the Journal. But as a “heavy-lift booster,” it said, it is a product designed to serve a market that’s suffering “significantly eroded commercial demand” and “uncertain commercial prospects.”

The problem, as the Journal (correctly) pointed out, is that thanks to advances in rocketry, electronics, and materials technology, “both national security and corporate satellites continue to get smaller and lighter” (and cheaper).

In 2016, a new Guinness World Record was set for the largest object to be 3D printed in one piece. The ABS/carbon fiber composite tool was 3D printed in 30 hours, and measured 17.5 feet long, 5.5 feet wide, and 1.5 feet tall. It was about as long as an average sport utility vehicle. The part was inarguably an impressive accomplishment – but that long length cannot compare to what Made In Space just 3D printed.

Made In Space is known for some pretty impressive accomplishments already. The company was responsible for the first 3D printer to be launched into space, and has since created a full Additive Manufacturing Facility (AMF) on the International Space station. Plenty of “firsts” have been set by the AMF as 3D printed tools, medical supplies, art and more have been 3D printed in space, the first of their kind. Now Made In Space has claimed the Guinness World Record for longest non-assembled 3D printed object, and it’s a lot longer than an SUV – it’s 37.7 meters, or 123 feet, 8.5 inches long.

That also happens to be the length of Made In Space’s Moffett Field facility at NASA’s Ames Research Center. The beam is now hanging from the ceiling of the facility. It was 3D printed with the company’s Extended Structure Additive Manufacturing Machine (ESAMM), which is the internal 3D printer of the Archinaut system. Archinaut uses robotic arms to assemble pre-fabricated and 3D printed components into larger, more complex structures, and will eventually be installed in space where it can autonomously repair things like satellites.

What if instead of blasting cargo into space on a rocket, we could fling it into space using a catapult? That’s the big, possibly crazy, possibly genius idea behind SpinLaunch. It was secretly founded in 2014 by Jonathan Yaney, who built solar-powered drone startup Titan Aerospace and sold it to Google. Now TechCrunch has learned from three sources that SpinLaunch is raising a massive $30 million Series A to develop its catapult technology. And we’ve scored an interview with the founder after four years in stealth.

Sources who’ve spoken to the SpinLaunch team tell me the idea is to create a much cheaper and sustainable way to get things like satellites from earth into space without chemical propellant. Using a catapult would sidestep the heavy fuel and expensive booster rockets used by companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin.

SpinLaunch plans to use a centrifuge spinning at an incredible rate inside a vacuum that reduces friction. All that momentum is then harnessed to catapult a payload into space at speeds one source said could be around 3,000 miles per hour. With enough momentum, objects could be flung into space on their own. Alternatively, the catapult could provide some of the power needed with cargo being equipped with supplemental rockets necessary to leave earth’s atmosphere.