NewScientist — March 10, 2009, by A. C. Grayling

IN THIS age of super-rapid technological advance, we do well to obey the Boy Scout injunction: “Be prepared”. That requires nimbleness of mind, given that the ever accelerating power of computers is being applied across such a wide range of applications, making it hard to keep track of everything that is happening. The danger is that we only wake up to the need for forethought when in the midst of a storm created by innovations that have already overtaken us.

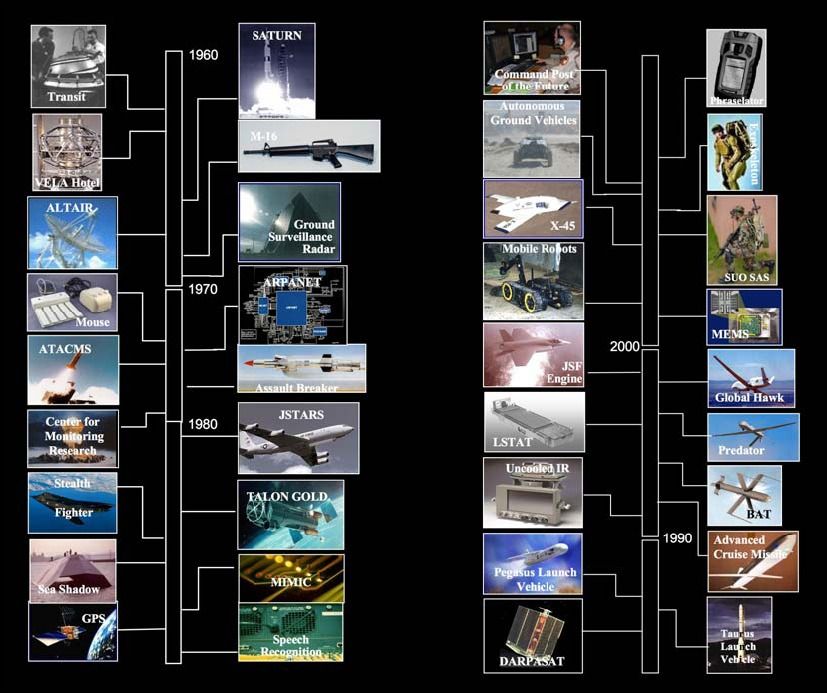

We are on the brink, and perhaps to some degree already over the edge, in one hugely important area: robotics. Robot sentries patrol the borders of South Korea and Israel. Remote-controlled aircraft mount missile attacks on enemy positions. Other military robots are already in service, and not just for defusing bombs or detecting landmines: a coming generation of autonomous combat robots capable of deep penetration into enemy territory raises questions about whether they will be able to discriminate between soldiers and innocent civilians. Police forces are looking to acquire miniature Taser-firing robot helicopters. In South Korea and Japan the development of robots for feeding and bathing the elderly and children is already advanced. Even in a robot-backward country like the UK, some vacuum cleaners sense their autonomous way around furniture. A driverless car has already negotiated its way through Los Angeles traffic.

In the next decades, completely autonomous robots might be involved in many military, policing, transport and even caring roles. What if they malfunction? What if a programming glitch makes them kill, electrocute, demolish, drown and explode, or fail at the crucial moment? Whose insurance will pay for damage to furniture, other traffic or the baby, when things go wrong? The software company, the manufacturer, the owner?

Most thinking about the implications of robotics tends to take sci-fi forms: robots enslave humankind, or beautifully sculpted humanoid machines have sex with their owners and then post-coitally tidy the room and make coffee. But the real concern lies in the areas to which the money already flows: the military and the police.

A confused controversy arose in early 2008 over the deployment in Iraq of three SWORDS armed robotic vehicles carrying M249 machine guns. The manufacturer of these vehicles said the robots were never used in combat and that they were involved in no “uncommanded or unexpected movements”. Rumours nevertheless abounded about the reason why funding for the SWORDS programme abruptly stopped. This case prompts one to prick up one’s ears.

Media stories about Predator drones mounting missile attacks in Afghanistan and Pakistan are now commonplace, and there are at least another dozen military robot projects in development. What are the rules governing their deployment? How reliable are they? One sees their advantages: they keep friendly troops out of harm’s way, and can often fight more effectively than human combatants. But what are the limits, especially when these machines become autonomous?

The civil liberties implications of robot devices capable of surveillance involving listening and photographing, conducting searches, entering premises through chimneys or pipes, and overpowering suspects are obvious. Such devices are already on the way. Even more frighteningly obvious is the threat posed by military or police-type robots in the hands of criminals and terrorists.

There needs to be a considered debate about the rules and requirements governing all forms of robot devices, not a panic reaction when matters have gone too far. That is how bad law is made — and on this issue time is running out.

A. C. Grayling is a philosopher at Birkbeck, University of London