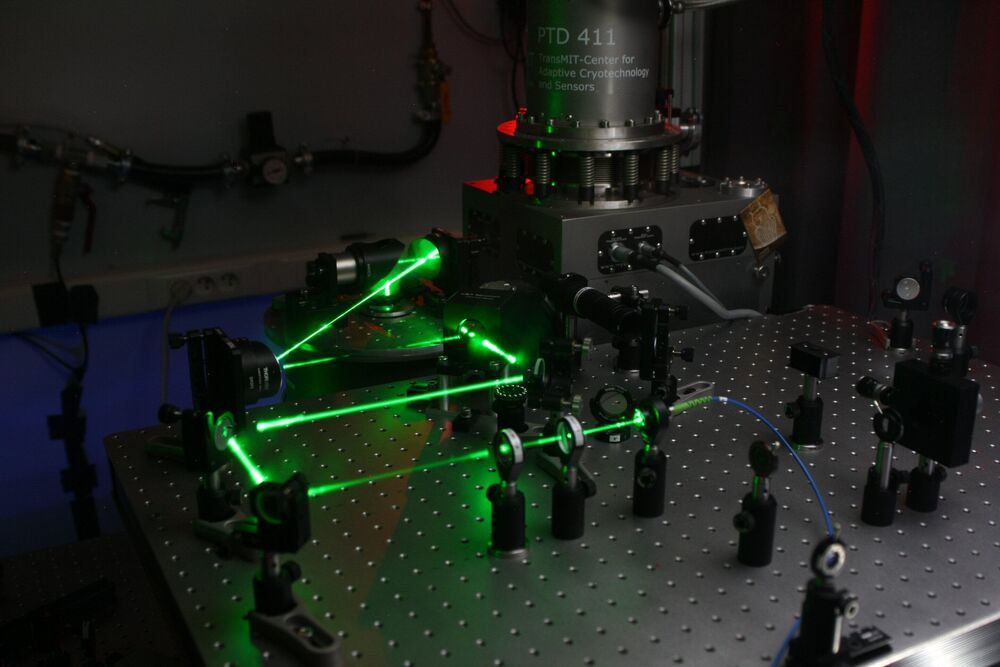

Researchers at Paderborn University have developed a new method of distance measurement for systems such as GPS, which achieves more precise results than ever before. Using quantum physics, the team led by Leibniz Prize winner Professor Christine Silberhorn has successfully overcome the so-called resolution limit, which causes the ‘noise’ we may see in photos, for example. Their findings have just been published in the academic journal Physical Review X Quantum (PRX Quantum).

Physicist Dr. Benjamin Brecht explains the problem of the resolution limit: “In laser distance measurements a detector registers two light pulses of different intensities with a time difference. The more precise the time measurement is, the more accurately the distance can be determined. Providing the time separation between the pulses is greater than the length of the pulses, this works well.” Problems arise, however, as Brecht explains, if the pulses overlap: “Then you can no longer measure the time difference using conventional methods. This is known as the ‘resolution limit’ and is a well-known effect in photos. Very small structures or textures can no longer be resolved. That’s the same problem—just with position rather than time.”

A further challenge, according to Brecht, is to determine the different intensities of two light pulses, simultaneously with their time difference and the arrival time. But this is exactly what the researchers have managed to do—” with quantum-limited precision,” adds Brecht. Working with partners from the Czech Republic and Spain, the Paderborn physicists were even able to measure these values when the pulses overlapped by 90 per cent. Brecht says: “This is far beyond the resolution limit. The precision of the measurement is 10000 times better. Using methods from quantum information theory, we can find new forms of measurement which overcome the limitations of established methods.”