U.K. start-up Arqit expects to launch a worldwide service for sharing unbreakable quantum-encrypted messages using satellites in 2023.

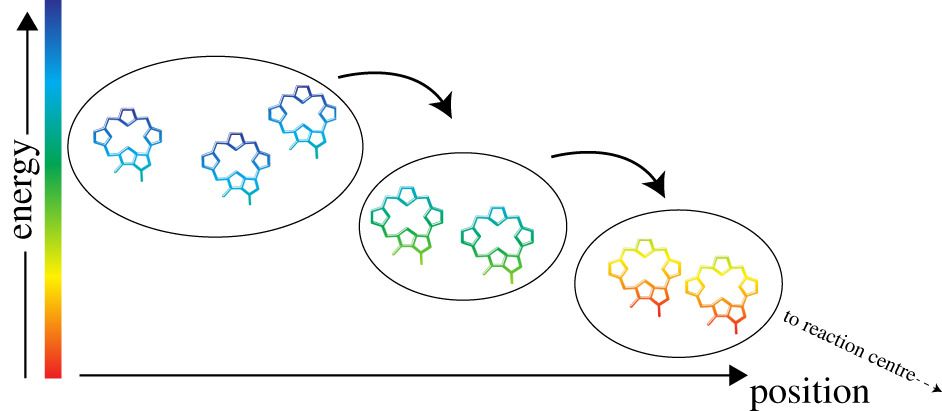

Biological systems are dynamical, constantly exchanging energy and matter with the environment in order to maintain the non-equilibrium state synonymous with living. Developments in observational techniques have allowed us to study biological dynamics on increasingly small scales. Such studies have revealed evidence of quantum mechanical effects, which cannot be accounted for by classical physics, in a range of biological processes. Quantum biology is the study of such processes, and here we provide an outline of the current state of the field, as well as insights into future directions.

Quantum mechanics is the fundamental theory that describes the properties of subatomic particles, atoms, molecules, molecular assemblies and possibly beyond. Quantum mechanics operates on the nanometre and sub-nanometre scales and is at the basis of fundamental life processes such as photosynthesis, respiration and vision. In quantum mechanics, all objects have wave-like properties, and when they interact, quantum coherence describes the correlations between the physical quantities describing such objects due to this wave-like nature.

In photosynthesis, respiration and vision, the models that have been developed in the past are fundamentally quantum mechanical. They describe energy transfer and electron transfer in a framework based on surface hopping. The dynamics described by these models are often ‘exponential’ and follow from the application of Fermi’s Golden Rule [1, 2]. As a consequence of averaging the rate of transfer over a large and quasi-continuous distribution of final states the calculated dynamics no longer display coherences and interference phenomena. In photosynthetic reaction centres and light-harvesting complexes, oscillatory phenomena were observed in numerous studies performed in the 1990s and were typically ascribed to the formation of vibrational or mixed electronic–vibrational wavepackets.

In 2013, François Englert and Peter Higgs won the Nobel Prize in Physics for the theoretical discovery of a mechanism that contributes to our understanding of the origin of mass of subatomic particles, which was confirmed through the discovery of the predicted fundamental particle by the A Toroidal LHC Apparatus (ATLAS) and the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) experiments at The European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN)’s Large Hadron Collider in 2012. The Higgs mode or the Anderson-Higgs mechanism (named after another Nobel Laureate Philip W Anderson), has widespread influence in our current understanding of the physical law for mass ranging from particle physics—the elusive “God particle” Higgs boson discovered in 2012 to the more familiar and important phenomena of superconductors and magnets in condensed matter physics and quantum material research.

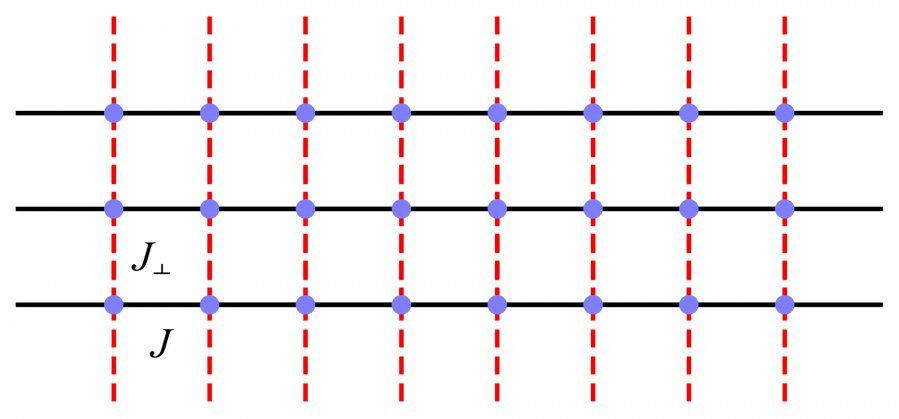

The Higgs mode, together with the Goldstone mode, is caused by the spontaneous breaking of continuous symmetries in the various quantum material systems. However, different from the Goldstone mode, which has been widely observed via neutron scattering and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopies in quantum magnets or superconductors, the observation of the Higgs mode in the material is much more challenging due to its usual overdamping, which is also the property in its particle physics cousin—the elusive Higgs boson. In order to weaken these damping, two paths have been suggested from the theoretical side, through quantum critical points and dimensional crossover from high dimensions to lower ones. For , people have achieved several remarkable results, whereas there are few successes in.

To fulfill this knowledge gap, from 2020, Mr Chengkang Zhou, then a first-year Ph.D. student, Dr. Zheng Yan and Dr. Zi Yang Meng from the Research Division for Physics and Astronomy of the University of Hong Kong (HKU), designed a dimensional crossover setting via coupled spin chains. They applied the quantum Monte Carlo (QMC) simulation to investigate the excitation spectra of the problem. Teaming up with Dr. Hanqing Wu from the Sun Yat-Sen University, Professor Kai Sun from the University of Michigan, and Professor Oleg A Starykh from the University of Utah, they observed three different kinds of collective excitation in the quasi-1D limit, including the Goldstone mode, the Higgs mode and the scalar mode. By combining numerical and analytic analyses, they successfully explained these excitations, and in particular, revealed the clear presence of the Higgs mode in the quasi-1D quantum magnetic systems.

“Stationary” has very different meanings at quantum and real-world scales – an object that looks perfectly still to us is actually made up of atoms that are buzzing and bouncing around. Now, scientists have managed to slow down the atoms almost to a complete stop in the largest macro-scale object yet.

The temperature of a given object is directly tied to the motion of its atoms – basically, the hotter something is, the more its atoms jiggle around. By extension, there’s a point where the object is so cold that its atoms come to a complete standstill, a temperature known as absolute zero (−273.15 °C,-459.67 °F).

Scientists have been able to chill atoms and groups of atoms to a fraction above absolute zero for decades now, inducing what’s called the motional ground state. This is a great starting point to then create exotic states of matter, such as supersolids, or fluids that seem to have negative mass.

Scientists are one step closer to solving general relativity’s biggest problem.

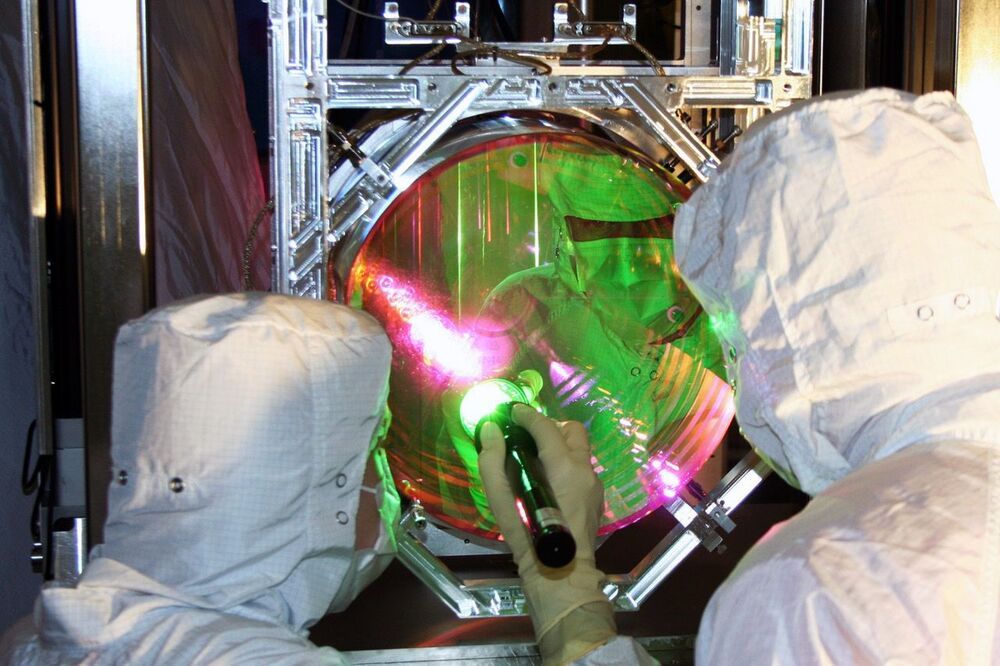

To do this, scientists used a new kind of observatory called LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory) that is fine-tuned to hunt for small disturbances in the fabric of spacetime caused by cosmic collisions, like black hole or neutron star mergers.

But this is only just the beginning of what LIGO can do, a team of international researchers reports in a new study published Thursday in the journal Science. Using new techniques to quantum cool LIGO’s mirrors, the team says that LIGO may soon also help them understand the quantum states of human-sized objects instead of just subatomic particles.

Vivishek Sudhir is a coauthor on the paper and assistant professor of mechanical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He tells Inverse that physicists have long theorized that gravity may be the culprit behind why large items don’t exhibit quantum behavior.

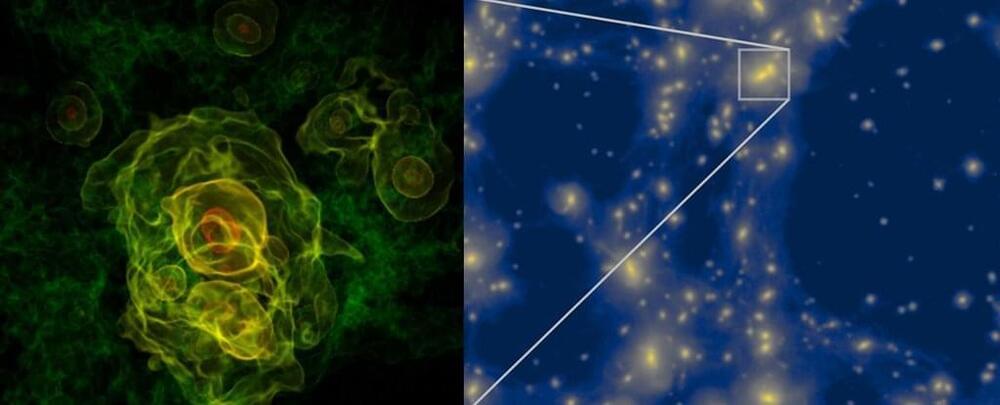

Peer long enough into the heavens, and the Universe starts to resemble a city at night. Galaxies take on characteristics of streetlamps cluttering up neighborhoods of dark matter, linked by highways of gas that run along the shores of intergalactic nothingness.

This map of the Universe was preordained, laid out in the tiniest of shivers of quantum physics moments after the Big Bang launched into an expansion of space and time some 13.8 billion years ago.

Yet exactly what those fluctuations were, and how they set in motion the physics that would see atoms pool into the massive cosmic structures we see today is still far from clear.

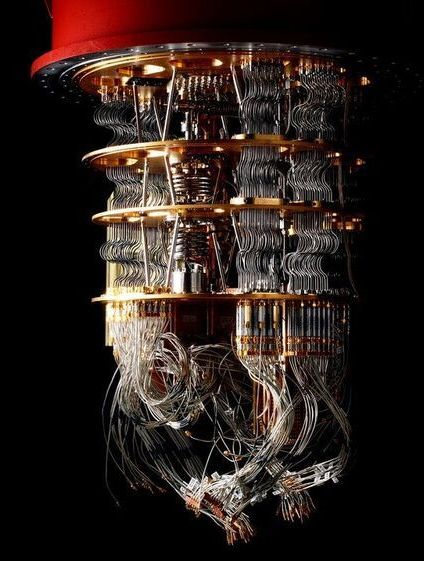

As the number of qubits in early quantum computers increases, their creators are opening up access via the cloud. IBM has its IBM Q network, for instance, while Microsoft has integrated quantum devices into its Azure cloud-computing platform. By combining these platforms with quantum-inspired optimisation algorithms and variable quantum algorithms, researchers could start to see some early benefits of quantum computing in the fields of chemistry and biology within the next few years. In time, Google’s Sergio Boixo hopes that quantum computers will be able to tackle some of the existential crises facing our planet. “Climate change is an energy problem – energy is a physical, chemical process,” he says.

“Maybe if we build the tools that allow the simulations to be done, we can construct a new industrial revolution that will hopefully be a more efficient use of energy.” But eventually, the area where quantum computers might have the biggest impact is in quantum physics itself.

The Large Hadron Collider, the world’s largest particle accelerator, collects about 300 gigabytes of data a second as it smashes protons together to try and unlock the fundamental secrets of the universe. To analyse it requires huge amounts of computing power – right now it’s split across 170 data centres in 42 countries. Some scientists at CERN – the European Organisation for Nuclear Research – hope quantum computers could help speed up the analysis of data by enabling them to run more accurate simulations before conducting real-world tests. They’re starting to develop algorithms and models that will help them harness the power of quantum computers when the devices get good enough to help.

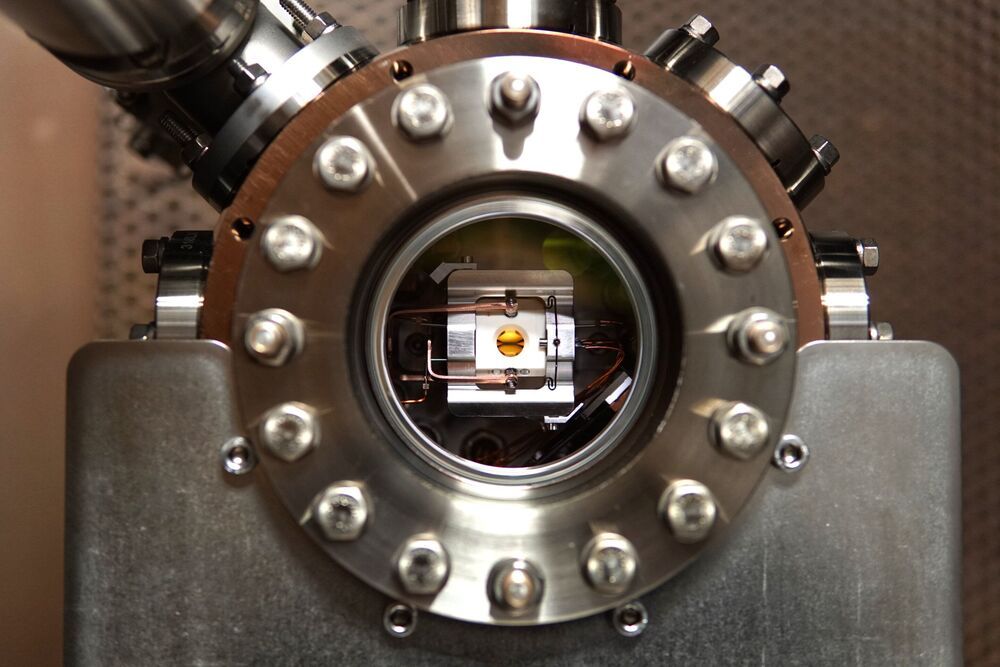

Quantum computers developed to date have been one-of-a-kind devices that fill entire laboratories. Now, physicists at the University of Innsbruck have built a prototype of an ion trap quantum computer that can be used in industry. It fits into two 19-inch server racks like those found in data centers throughout the world. The compact, self-sustained device demonstrates how this technology will soon be more accessible.

Over the past three decades, fundamental groundwork for building quantum computers has been pioneered at the University of Innsbruck, Austria. As part of the EU Flagship Quantum Technologies, researchers at the Department of Experimental Physics in Innsbruck have now built a demonstrator for a compact ion trap quantum computer. “Our quantum computing experiments usually fill 30-to 50-square-meter laboratories,” says Thomas Monz of the University of Innsbruck. “We were now looking to fit the technologies developed here in Innsbruck into the smallest possible space while meeting standards commonly used in industry.” The new device aims to show that quantum computers will soon be ready for use in data centers. “We were able to show that compactness does not have to come at the expense of functionality,” adds Christian Marciniak from the Innsbruck team.

The individual building blocks of the world’s first compact quantum computer had to be significantly reduced in size. For example, the centerpiece of the quantum computer, the ion trap installed in a vacuum chamber, takes up only a fraction of the space previously required. It was provided to the researchers by Alpine Quantum Technologies (AQT), a spin-off of the University of Innsbruck and the Austrian Academy of Sciences which aims to build a commercial quantum computer. Other components were contributed by the Fraunhofer Institute for Applied Optics and Precision Engineering in Jena and laser specialist TOPTICA Photonics in Munich, Germany.