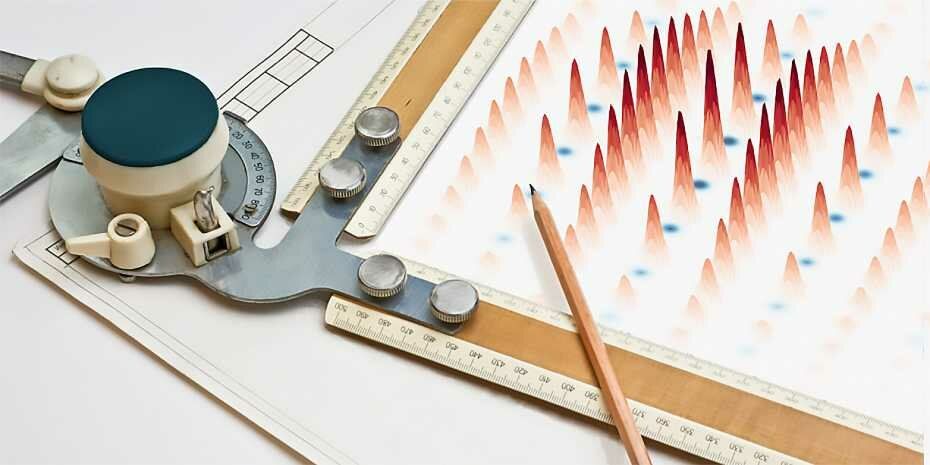

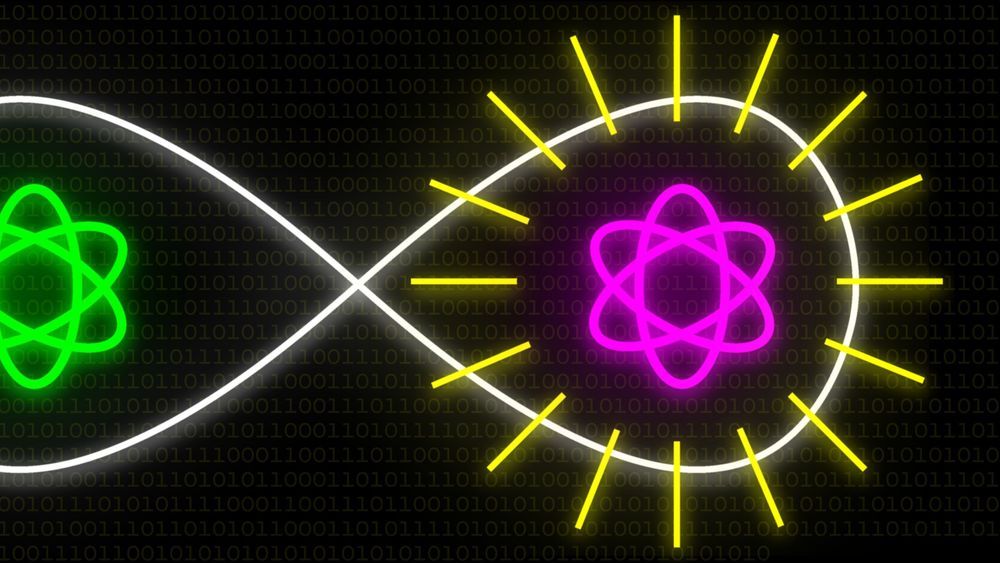

For the first time, researchers have demonstrated a way to map and measure large-scale photonic quantum correlation with single-photon sensitivity. The ability to measure thousands of instances of quantum correlation is critical for making photon-based quantum computing practical.

In Optica, The Optica l Society’s journal for high impact research, a multi-institutional group of researchers reports the new measurement technique, which is called correlation on spatially-mapped photon-level image (COSPLI). They also developed a way to detect signals from single photons and their correlations in tens of millions of images.

“COSPLI has the potential to become a versatile solution for performing quantum particle measurements in large-scale photonic quantum computers,” said the research team leader Xian-Min Jin, from Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China. “This unique approach would also be useful for quantum simulation, quantum communication, quantum sensing and single-photon biomedical imaging.”