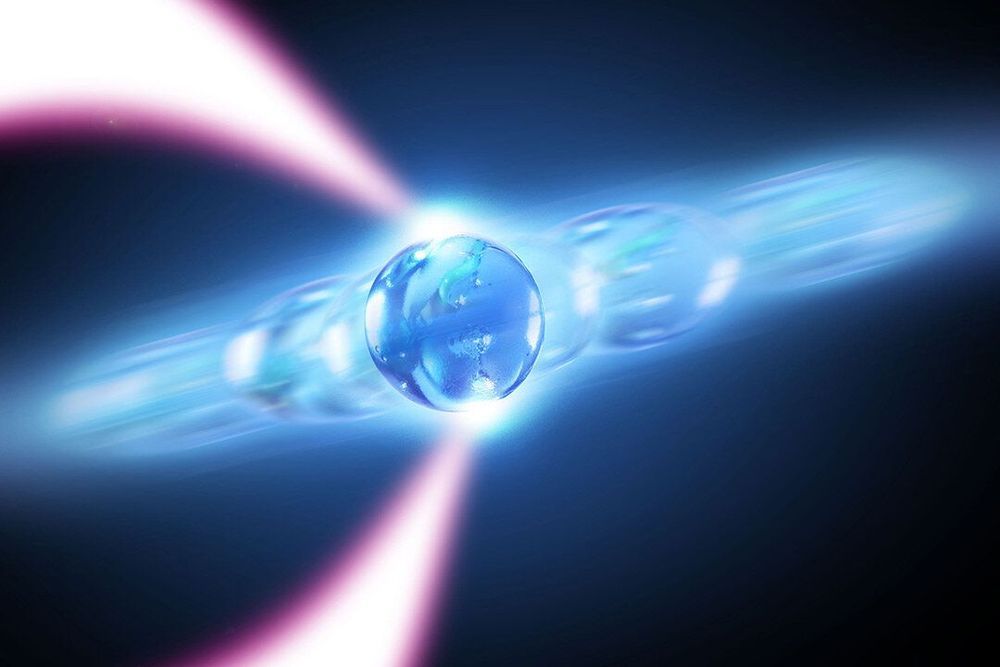

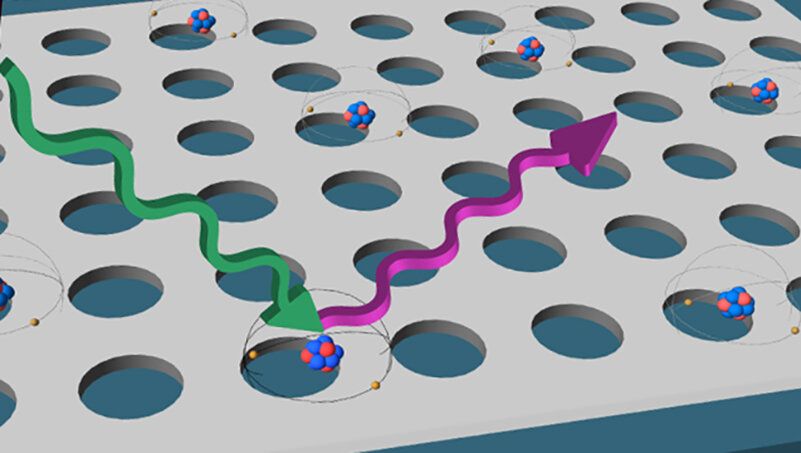

In quantum physics, a vacuum is not empty, but rather steeped in tiny fluctuations of the electromagnetic field. Until recently it was impossible to study those vacuum fluctuations directly. Researchers at ETH Zurich have developed a method that allows them to characterize the fluctuations in detail.

Emptiness is not really empty – not according to the laws of quantum physics, at any rate. The vacuum, in which classically there is supposed to be “nothing,” teems with so-called vacuum fluctuations according to quantum mechanics. Those are small excursions of an electromagnetic field, for instance, that average out to zero over time but can deviate from it for a brief moment. Jérôme Faist, professor at the Institute for Quantum Electronics at ETH in Zurich, and his collaborators have now succeeded in characterizing those vacuum fluctuations directly for the first time.

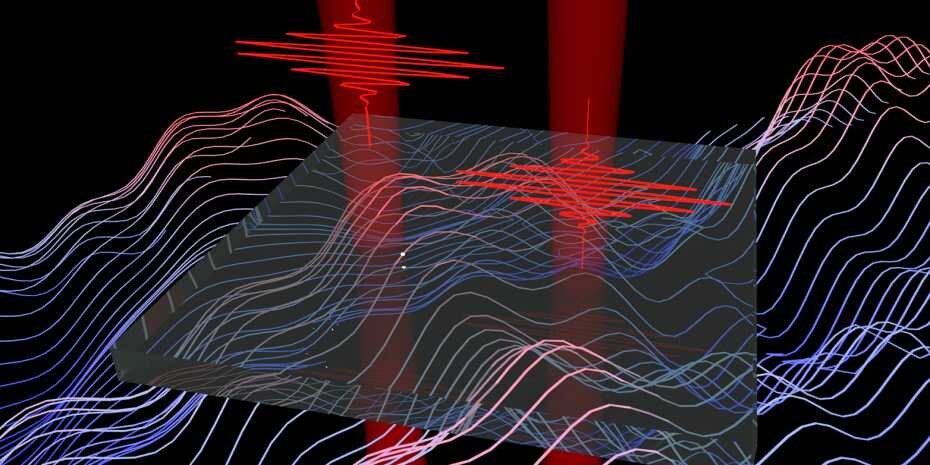

“The vacuum fluctuations of the electromagnetic field have clearly visible consequences, and among other things, are responsible for the fact that an atom can spontaneously emit light,” explains Ileana-Cristina Benea-Chelmus, a recently graduated Ph.D. student in Faists laboratory and first author of the study recently published in the scientific journal Nature. “To measure them directly, however, seems impossible at first sight. Traditional detectors for light such as photodiodes are based on the principle that light particles – and hence energy – are absorbed by the detector. However, from the vacuum, which represents the lowest energy state of a physical system, no further energy can be extracted.”

Read more