Circa 2018

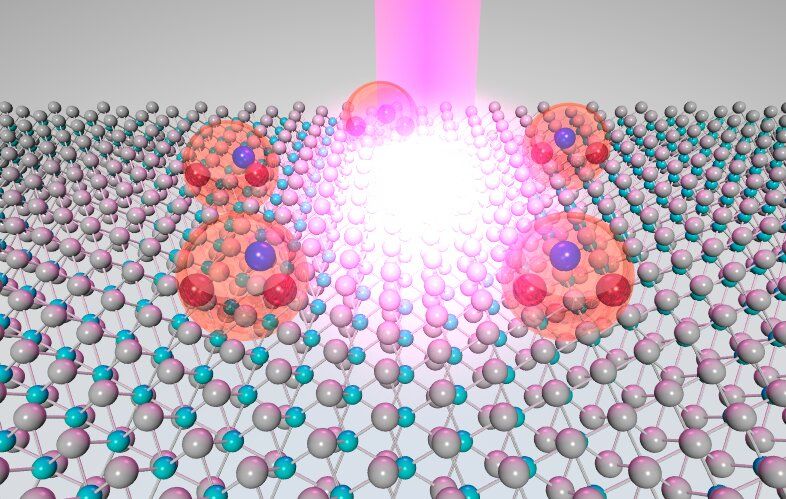

The symmetries that govern the world of elementary particles at the most elementary level could be radically different from what has so far been thought. This surprising conclusion emerges from new work published by theoreticians from Warsaw and Potsdam. The scheme they posit unifies all the forces of nature in a way that is consistent with existing observations and anticipates the existence of new particles with unusual properties, which may even be present in our close environs.

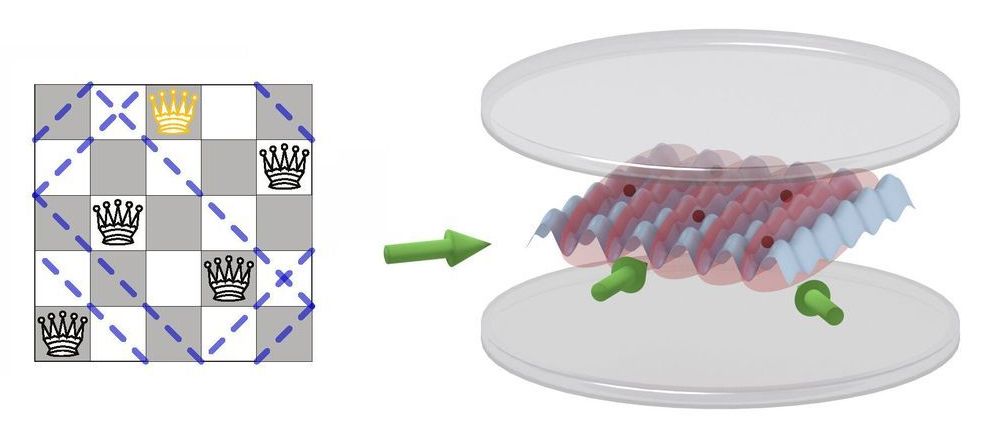

For half a century, physicists have been trying to construct a theory that brings together all four fundamental forces of nature, describes the known elementary particles and predicts the existence of new ones. So far these attempts have not found experimental confirmation and the Standard Model — an old and surely incomplete, but still surprisingly effective theoretical construct — has successfully remained in use for years as our best description of the quantum world. In a recent paper in Physical Review Letters, Prof. Krzysztof Meissner from the Institute of Theoretical Physics, Faculty of Physics, University of Warsaw, and Prof. Hermann Nicolai from the Max-Planck-Institut für Gravitationsphysik in Potsdam have presented a new scheme generalizing the Standard Model that incorporates gravitation into the description. The shortcomings of previous attempts were overcome through the application of a kind of symmetry not previously used in the description of elementary particles.

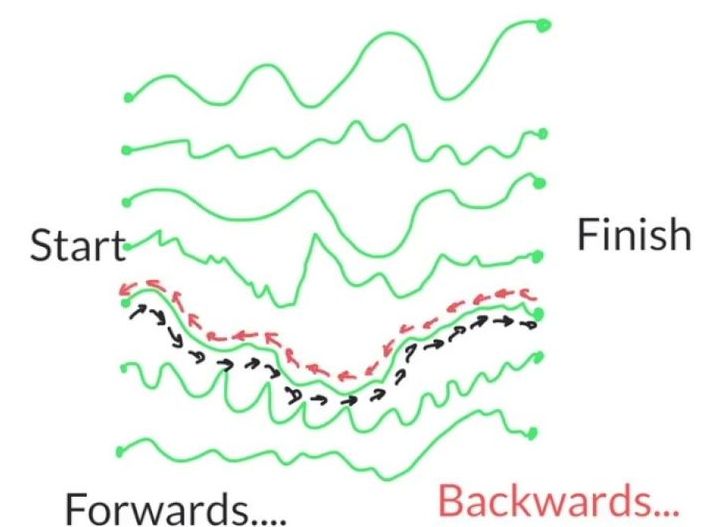

In physics, symmetries are understood somewhat differently than in the colloquial sense of the word. For instance, note that whether we drop a ball from the same spot now or one minute from now, it will still fall in the same way. That is a manifestation of a certain symmetry: the laws of physics remain unchanged with respect to shifts in time. Similarly, we can drop the ball while standing and facing once in a southward direction, once westward, or we can drop it from the same height in one location, then another. The ball will still fall in the same way in both cases, which means that the laws of physics are symmetrical also with respect to the operations of rotation and spatial displacement, respectively.