This newly discovered superconducting material could be the building blocks for Quantum Computers.

Quantum computers with the ability to perform complex calculations, encrypt data more securely and more quickly predict the spread of viruses, may be within closer reach thanks to a new discovery by Johns Hopkins researchers.

“We’ve found that a certain superconducting material contains special properties that could be the building blocks for technology of the future,” says Yufan Li, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Physics & Astronomy at The Johns Hopkins University and the paper’s first author.

The findings will be published October 11 in Science.

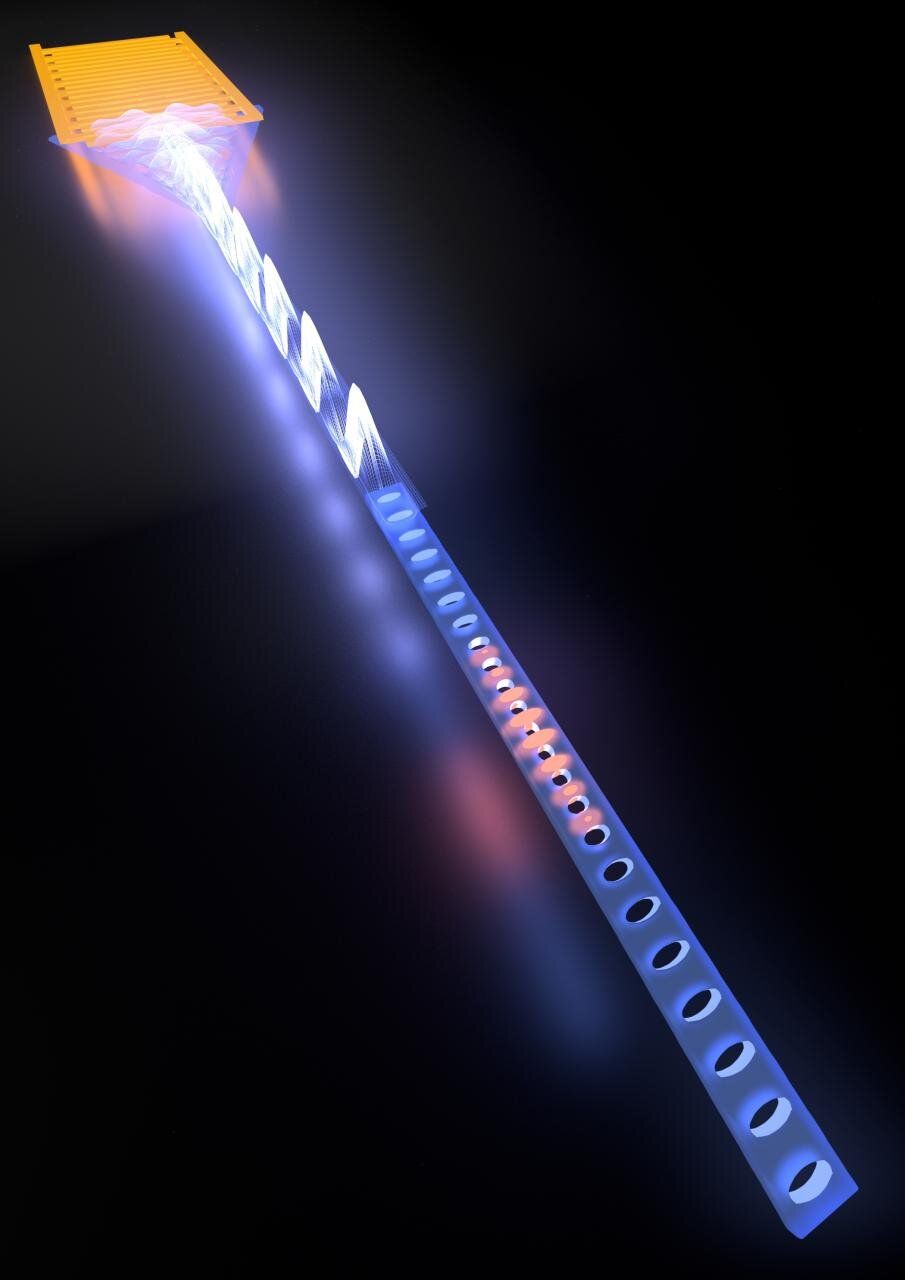

Researchers led by Delft University of Technology personnel have made two steps in the conversion of quantum states between signals in the microwave and optical domains. This is of great interest for connecting future superconducting quantum computers into a global quantum network. This week they report on their findings in Nature Physics and in Physical Review Letters.

Conversion between signals in the microwave and optical domains is of great interest, particularly for connecting future superconducting quantum computers into a global quantum network. Many leading efforts in quantum technologies, including superconducting qubits and quantum dots, share quantum information through photons in the microwave regime. While this allows for an impressive degree of quantum control, it also limits the distance the information can realistically travel before being lost to a mere few centimeters.

At the same time, the field of optical quantum communication has already seen demonstrations over distance scales capable of providing real-world applications. By transmitting information in the optical telecom band, fiber-based quantum networks over tens or even hundreds of kilometers can be envisaged. “In order to connect several quantum computing nodes over large distances into a quantum internet, it is therefore vital to be able to convert quantum information from the microwave to the optical domain, and back,” says Prof. Simon Groeblacher of Delft University of Technology. “This will not only be extremely interesting for quantum applications, but also for highly efficient, low-noise conversion between classical optical and electrical signals.”

Scientists have observed a quantum vibration at normal room temperature for the first time, a phenomenon that usually requires ultra-cold, carefully calibrated conditions – bringing us another step closer to understanding the behaviour of quantum mechanics in common materials.

The team was able to spot a phonon, a quantum particle of vibration generated from high-frequency laser pulses, in a piece of diamond. These phonons are notoriously hard to detect, partly because of their sensitivity to heat.

What makes observing a phonon so important is that it shows a vibration acting as a single unit of energy (as described by quantum mechanics), as well as a wave (as described by classical physics). At room temperature in open air conditions, it brings quantum behaviour “closer to our daily life” in the words of the researchers.

In a certain sense, physics is the study of the universe’s symmetries. Physicists strive to understand how systems and symmetries change under various transformations.

New research from Washington University in St. Louis realizes one of the first parity-time (PT) symmetric quantum systems, allowing scientists to observe how that kind of symmetry—and the act of breaking of it—leads to previously unexplored phenomena. The work from the laboratory of Kater Murch, associate professor of physics in Arts & Sciences, is published Oct. 7 in the journal Nature Physics.

Other experiments have demonstrated PT symmetry in classical systems such as coupled pendulums or optical devices, but this new work in Murch’s lab, along with experiments in China by Yang Wu et al., reported in Science this May, provides the first experimental realization of a PT-symmetric quantum system.

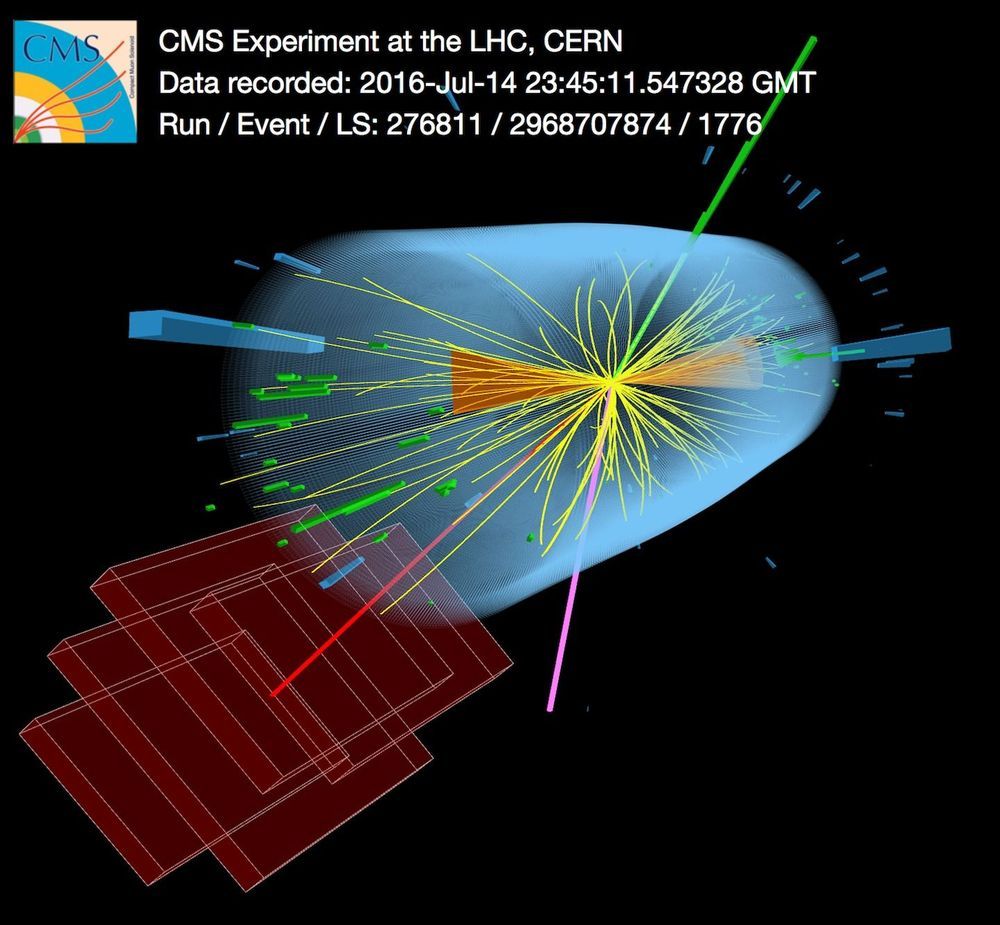

Dive into the subatomic world, into the heart of protons or neutrons, and you’ll find elementary particles known as quarks. Measuring the mass of these quarks can be challenging, but new results from the CMS collaboration reveal for the first time how the mass of the top quark – the heaviest of six types of quarks – varies depending on the energy scale used to measure the particle.

The theory of quantum chromodynamics, a component of the Standard Model, predicts this energy-scale variation, known as running, for the masses of all quarks and for the strong force acting between them. Observing the running masses of quarks can therefore provide a way of testing quantum chromodynamics and the Standard Model.

Experiments at CERN and other laboratories have already measured the running masses of the bottom and charm quarks, the second and third heaviest quarks, and the results were in agreement with quantum chromodynamics. Now, the CMS collaboration has used data from high-energy proton–proton collisions at the Large Hadron Collider to chase out the running mass of the top quark.

One of the fundamental challenges of physics is the reconciliation of Einstein’s theory of relativity and quantum mechanics. The necessity to critically question these two pillars of modern physics arises, for example, from extremely high-energy events in the cosmos, which so far can only ever be explained by one theory at a time, but not both theories in harmony. Researchers around the world are therefore searching for deviations from the laws of quantum mechanics and relativity that could open up insights into a new field of physics.

For a recent publication, scientists from Leibniz University Hannover and Ulm University have taken on the twin paradox known from Einstein’s special theory of relativity. This thought experiment revolves around a pair of twins: While one brother travels into space, the other remains on Earth. Consequently, for a certain period of time, the twins are moving in different orbits in space. The result when the pair meets again is quite astounding: The twin who has been travelling through space has aged much less than his brother who stayed at home. This phenomenon is explained by Einstein’s description of time dilation: Depending on the speed and where in the gravitational field two clocks move relative to each other, they tick at different speeds.

For the publication in Science Advances, the authors assumed a quantum-mechanical variant of the twin paradox with only one twin. Thanks to the superposition principle of quantum mechanics, this twin can move along two paths at the same time. In the researchers’ thought experiment, the twin is represented by an atomic clock. “Such clocks use the quantum properties of atoms to measure time with high precision. The atomic clock itself is therefore a quantum-mechanical object and can move through space-time on two paths simultaneously due to the superposition principle. Together with colleagues from Hannover, we have investigated how this situation can be realised in an experiment,” explains Dr. Enno Giese, research assistant at the Institute of Quantum Physics in Ulm. To this end, the researchers have developed an experimental setup for this scenario on the basis of a quantum-physical model.

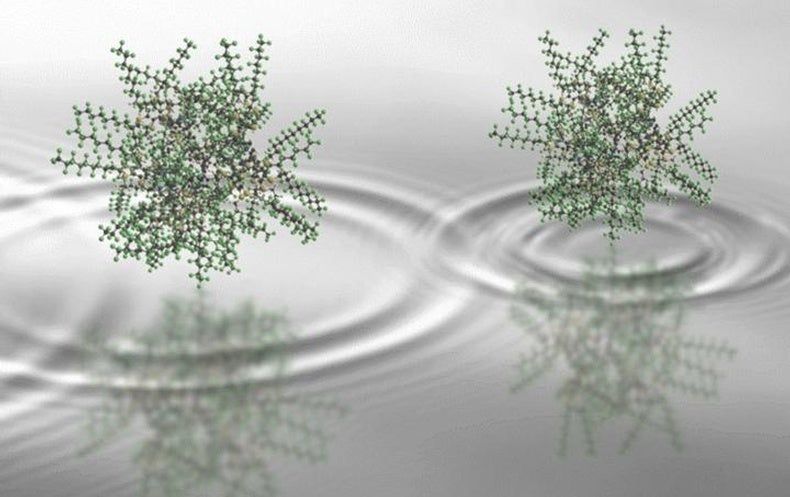

Research led by University of Texas at Dallas physicists has altered the understanding of the fundamental properties of perovskite crystals, a class of materials with great potential as solar cells and light emitters.

Published in July in Nature Communications, the study presents evidence that questions existing models of the behavior of perovskites on the quantum level.

“Our enhanced understanding of the physics of perovskites will help determine how they are best used,” said Dr. Anton Malko, associate professor of physics in the School of Natural Sciences and Mathematics and a corresponding author of the paper.

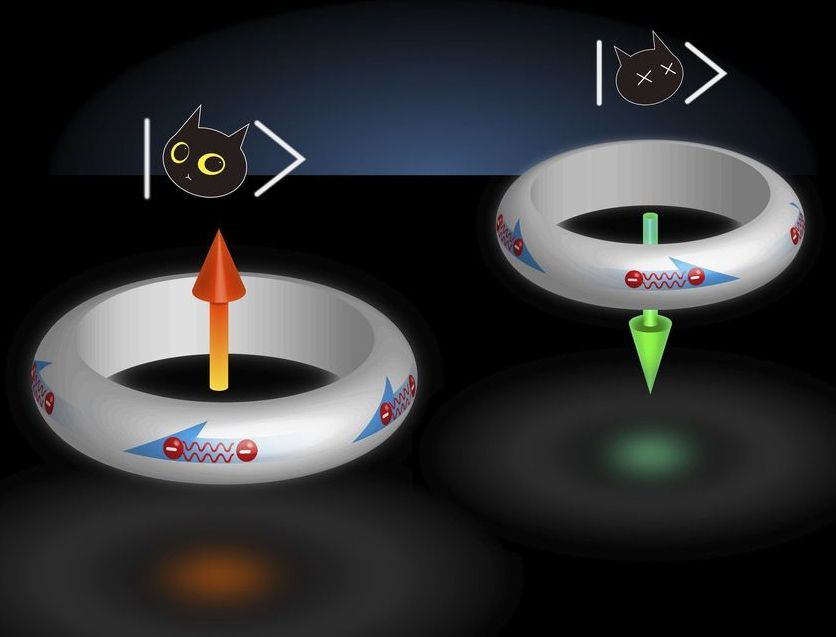

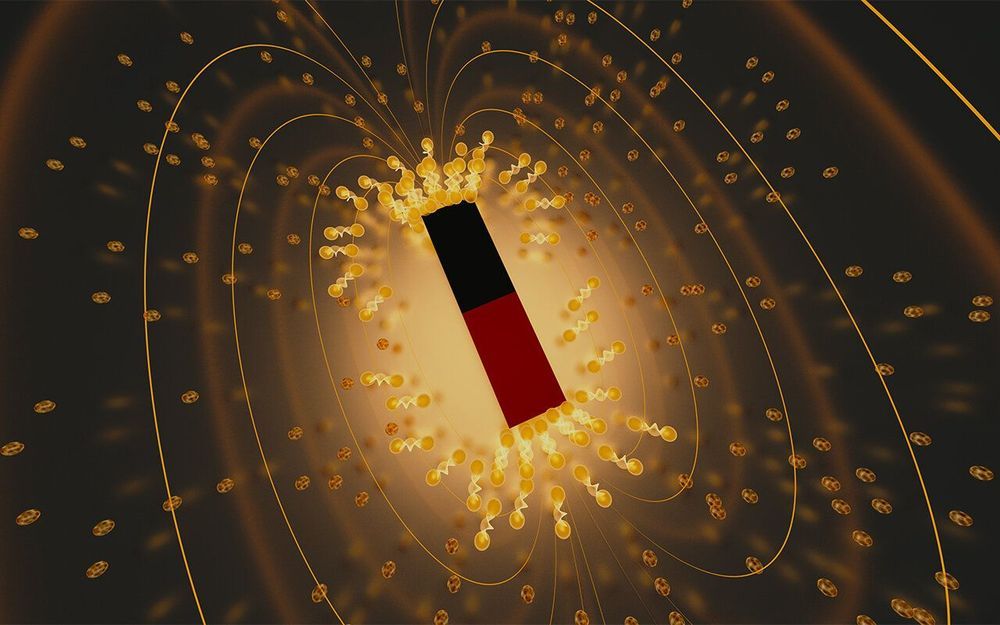

Researchers from the University of Maryland, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory (NHMFL) and the University of Oxford have observed a rare phenomenon called re-entrant superconductivity in the material uranium ditelluride. The discovery furthers the case for uranium ditelluride as a promising material for use in quantum computers.

Nicknamed “Lazarus superconductivity” after the biblical character who rose from the dead, the phenomenon occurs when a superconducting state arises, breaks down, then re-emerges in a material due to a change in a specific parameter—in this case, the application of a very strong magnetic field. The researchers published their results on October 7, 2019, in the journal Nature Physics.

Once dismissed by physicists for its apparent lack of interesting physical properties, uranium ditelluride is having its own Lazarus moment. The current study is the second in as many months (both published by members of the same research team) to demonstrate unusual and surprising superconductivity states in the material.