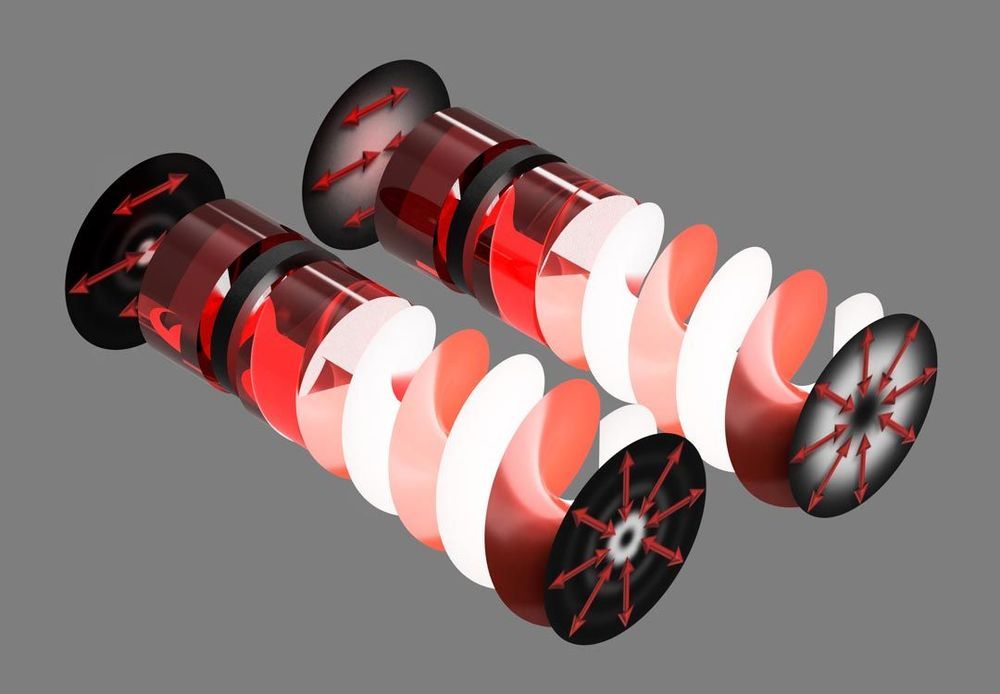

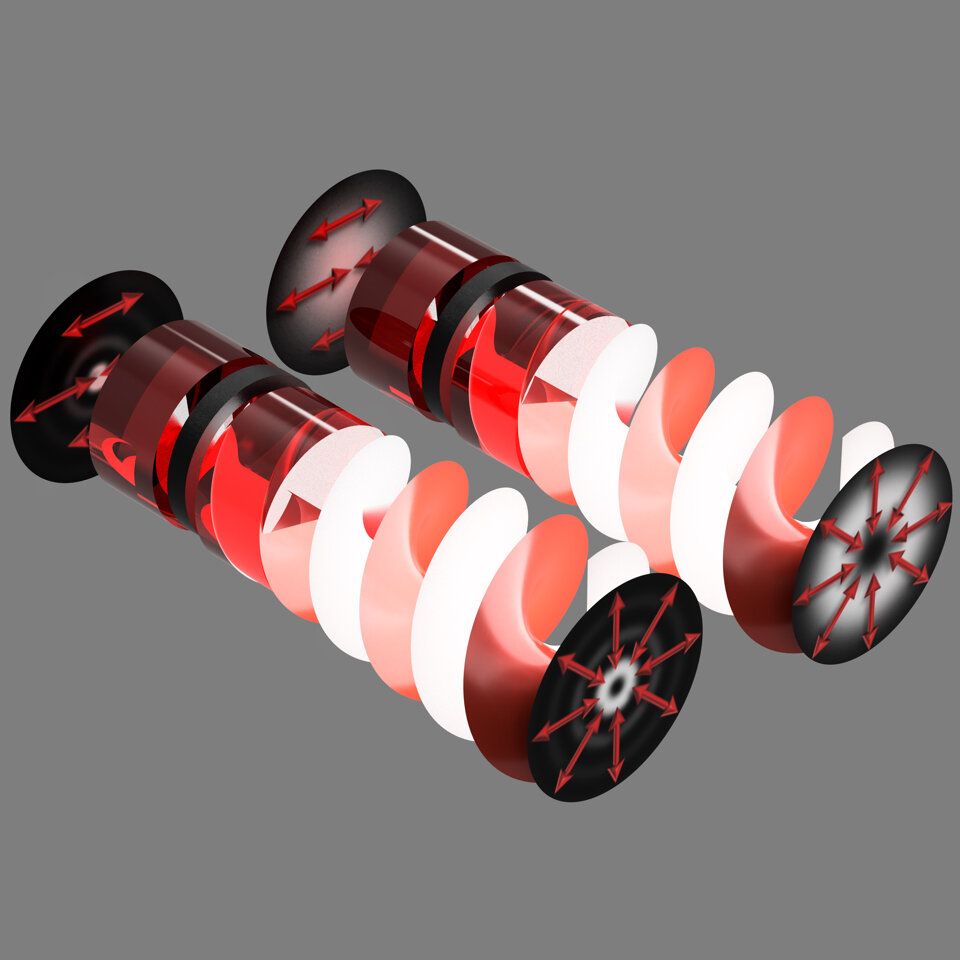

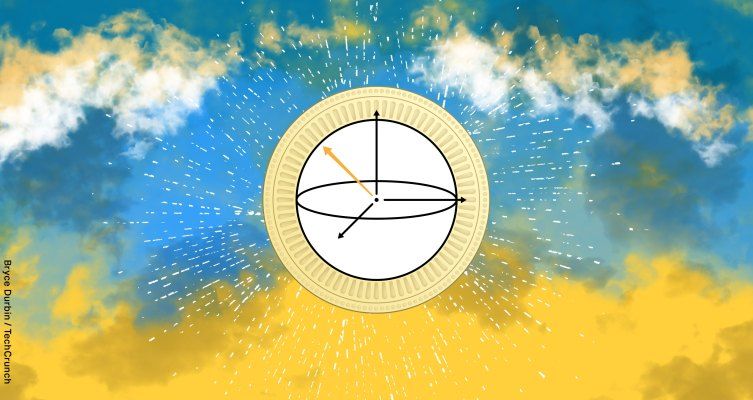

EPFL researchers, with colleagues at the University of Cambridge and IBM Research-Zurich, unravel novel dynamics in the interaction between light and mechanical motion with significant implications for quantum measurements designed to evade the influence of the detector in the notorious ‘back action limit’ problem.

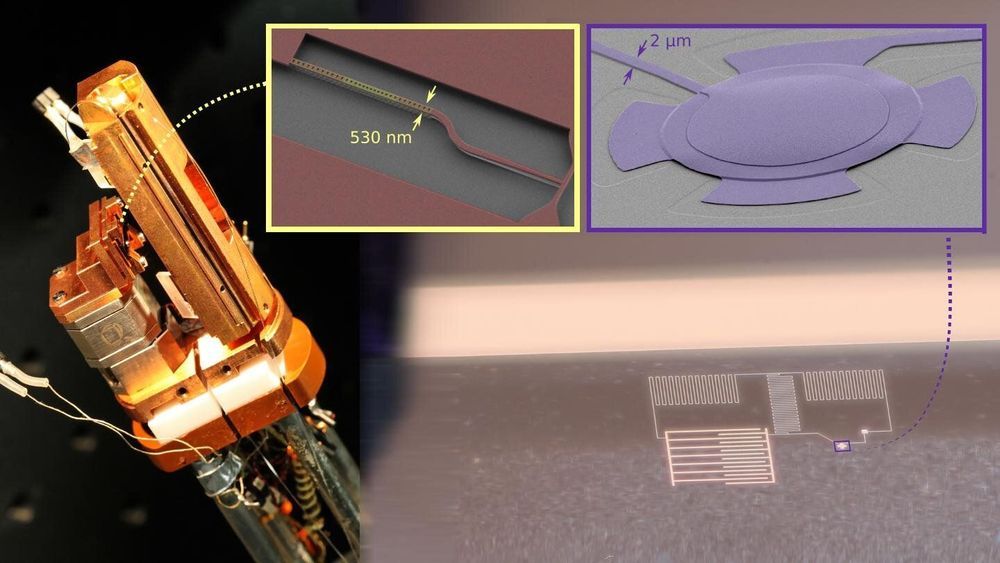

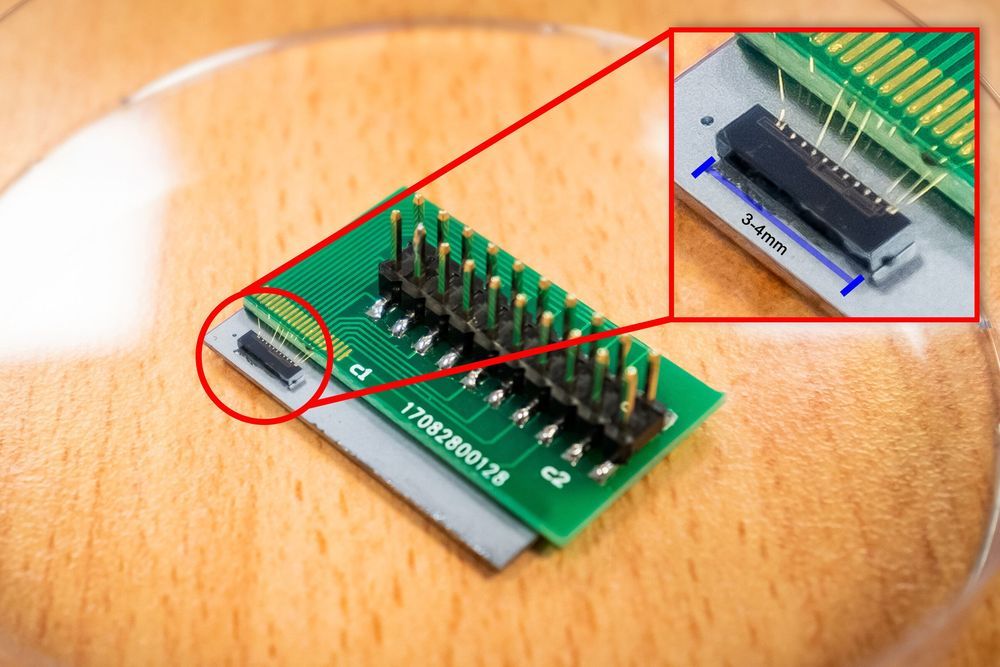

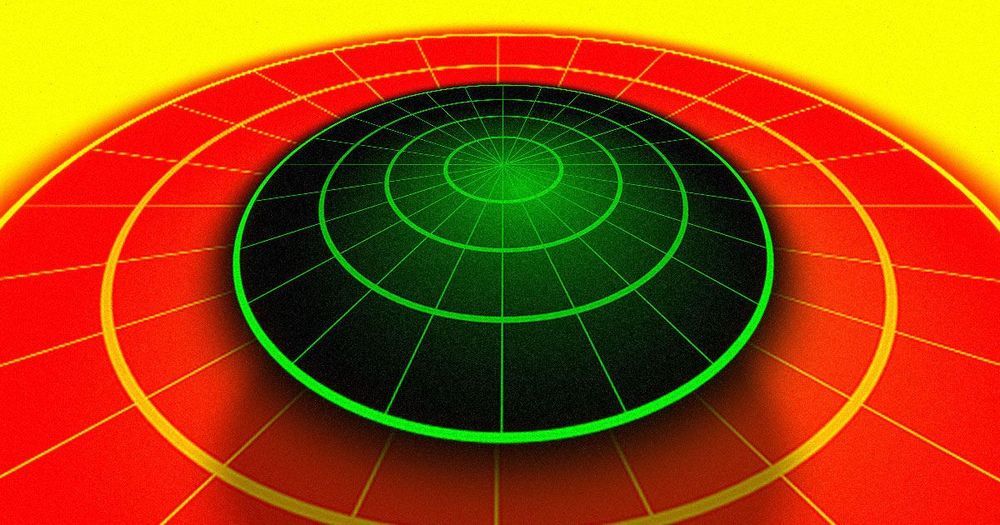

The limits of classical measurements of mechanical motion have been pushed beyond expectations in recent years, e.g. in the first direct observation of gravitational waves, which were manifested as tiny displacements of mirrors in kilometer-scale optical interferometers. On the microscopic scale, atomic- and magnetic-resonance force microscopes can now reveal the atomic structure of materials and even sense the spins of single atoms.

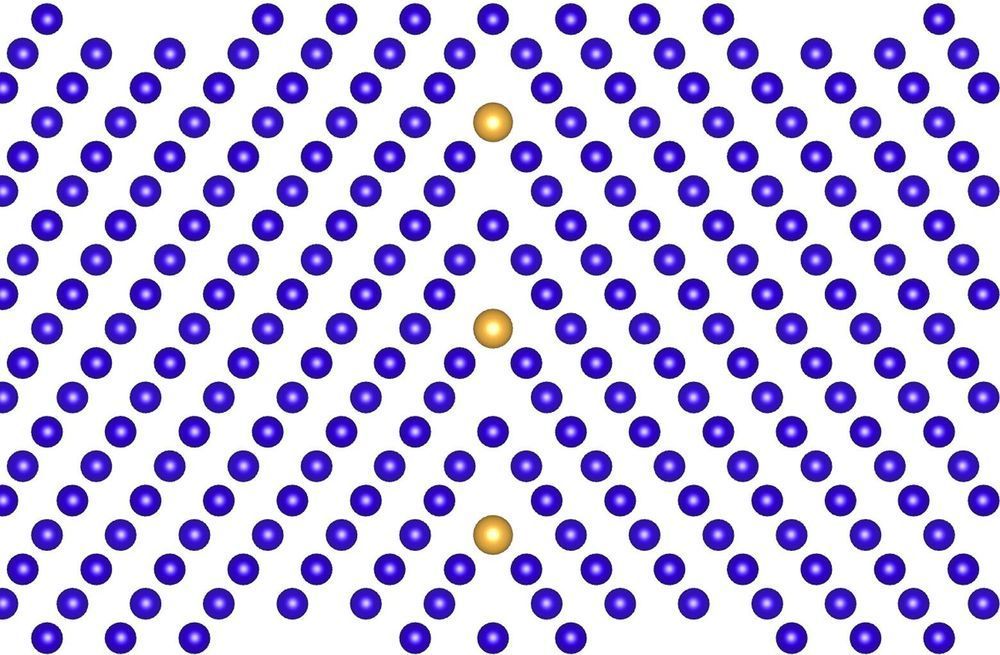

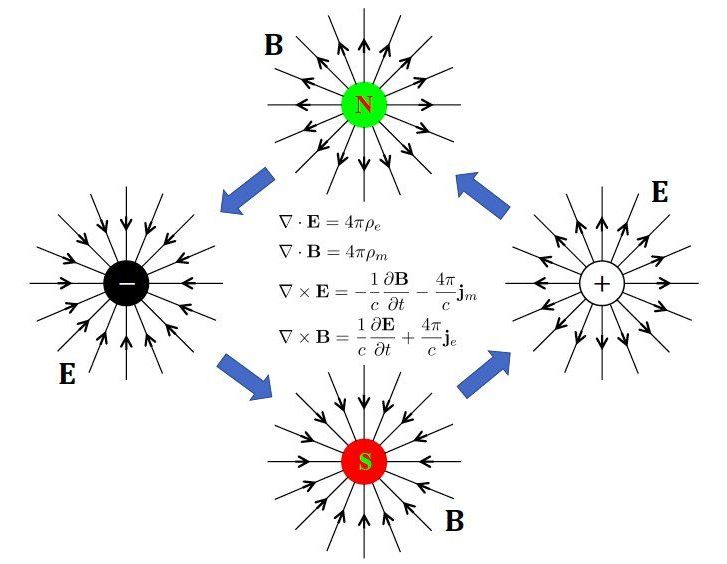

But the sensitivity that we can achieve using purely conventional means is limited. For example, Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle in quantum mechanics implies the presence of “measurement backaction”: the exact knowledge of the location of a particle invariably destroys any knowledge of its momentum, and thus of predicting any of its future locations.