O.o.

We’re close to being uncertain about where hundreds of millions of atoms are.

Essentially the higgs mode is like a developer mode for materials and even physics by itself. It could make metals that are as light as a feather but essentially as strong as a universe. It could make essentially near infinitely strong metals that could be put on spaceships to handle all manners of energy blasts. Even weird things could happen where like even changing dimension al physics of areas. Essentially a near cartoon like physics or even prove the existence of the stranger things dimension really happened. Even keep out other dimensions from entering our universe. Even controlling the universe itself by healing it. Essentially like it could allow the monitor from halo kinda developer mode to modify gravity or all variables or even bring new variables into the dimension.

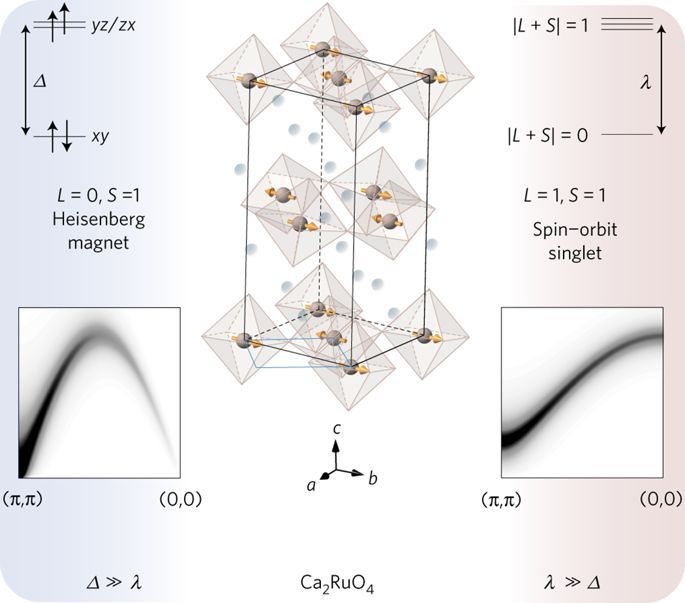

Condensed-matter analogues of the Higgs boson in particle physics allow insights into its behaviour in different symmetries and dimensionalities1. Evidence for the Higgs mode has been reported in a number of different settings, including ultracold atomic gases2, disordered superconductors3, and dimerized quantum magnets4. However, decay processes of the Higgs mode (which are eminently important in particle physics) have not yet been studied in condensed matter due to the lack of a suitable material system coupled to a direct experimental probe. A quantitative understanding of these processes is particularly important for low-dimensional systems, where the Higgs mode decays rapidly and has remained elusive to most experimental probes. Here, we discover and study the Higgs mode in a two-dimensional antiferromagnet using spin-polarized inelastic neutron scattering. Our spin-wave spectra of Ca2RuO4 directly reveal a well-defined, dispersive Higgs mode, which quickly decays into transverse Goldstone modes at the antiferromagnetic ordering wavevector. Through a complete mapping of the transverse modes in the reciprocal space, we uniquely specify the minimal model Hamiltonian and describe the decay process. We thus establish a novel condensed-matter platform for research on the dynamics of the Higgs mode.

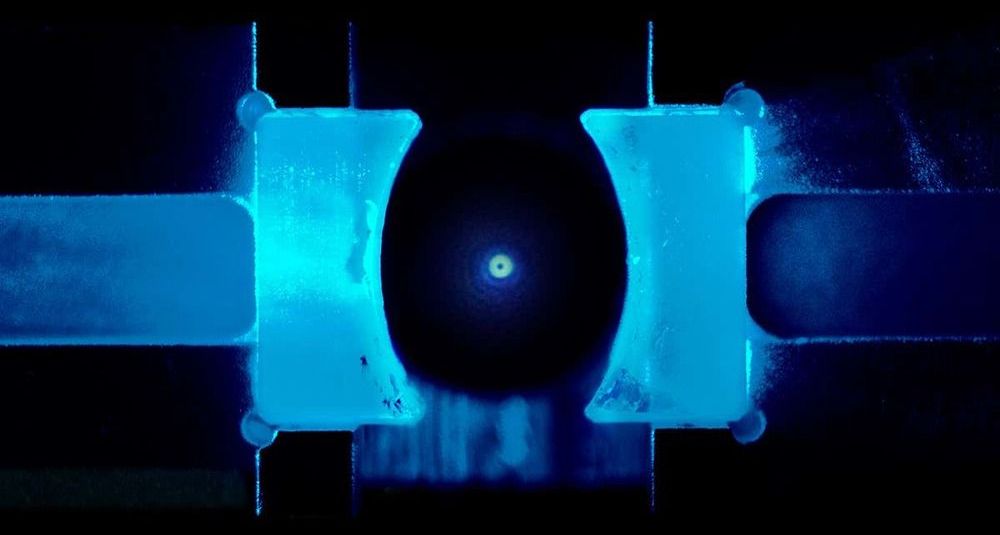

A new method for manipulating the quantum state of particles could one day allow us to observe an object in two places at once. The technique has been used to chill a tiny glass bead into its coldest possible quantum state.

Once you get down to extremely small scales, heat and motion are interchangeable: the more a particle is moving, the hotter it is. So to cool down a small particle, you have to stop it moving. Because the rules of quantum mechanics mean you can never know exactly how fast a particle is moving, there is a limit to how cold a particle can get. When a particle is at that limit, we call it the particle’s ground state.

Essentially the higgs boson could create a replicator and even a teleportation device.

Can you think of any? Here’s what I mean. When we set about justifying basic research in fundamental science, we tend to offer multiple rationales. One (the easy and most obviously legitimate one) is that we’re simply curious about how the world works, and discovery is its own reward. But often we trot out another one: the claim that applied research and real technological advances very often spring from basic research with no specific technological goal. Faraday wasn’t thinking of electronic gizmos when he helped pioneer modern electromagnetism, and the inventors of quantum mechanics weren’t thinking of semiconductors and lasers. They just wanted to figure out how nature works, and the applications came later.

So what about contemporary particle physics, and the Higgs boson in particular? We’re spending a lot of money to look for it, and I’m perfectly comfortable justifying that expense by the purely intellectual reward associated with understanding the missing piece of the Standard Model of particle physics. But inevitably we also mention that, even if we don’t know what it will be right now, it’s likely (or some go so far as to say “inevitable”) that someday we’ll invent some marvelous bit of technology that makes crucial use of what we learned from studying the Higgs. So — anyone have any guesses as to what that might be? You are permitted to think broadly here. We’re obviously not expecting something within a few years after we find the little bugger. So imagine that we have discovered it, and if you like you can imagine we have the technology to create Higgses with a lot less overhead than a kilometers-across particle accelerator.

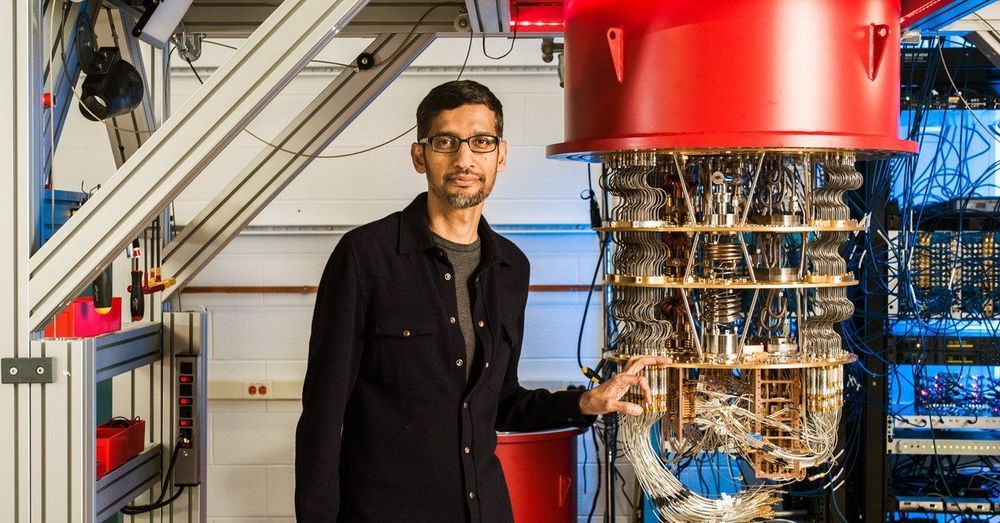

“Think what we can do if we teach a quantum computer to do statistical mechanics,” posed Michael McGuigan, a computational scientist with the Computational Science Initiative at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory.

At the time, McGuigan was reflecting on Ludwig Boltzmann and how the renowned physicist had to vigorously defend his theories of statistical mechanics. Boltzmann, who proffered his ideas about how atomic properties determine physical properties of matter in the late 19th century, had one extraordinarily huge hurdle: atoms were not even proven to exist at the time. Fatigue and discouragement stemming from his peers not accepting his views on atoms and physics forever haunted Boltzmann.

Today, Boltzmann’s factor, which calculates the probability that a system of particles can be found in a specific energy state relative to zero energy, is widely used in physics. For example, Boltzmann’s factor is used to perform calculations on the world’s largest supercomputers to study the behavior of atoms, molecules, and the quark “soup” discovered using facilities such as the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider located at Brookhaven Lab and the Large Hadron Collider at CERN.

A team from the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory has conducted a series of experiments to gain a better understanding of quantum mechanics and pursue advances in quantum networking and quantum computing, which could lead to practical applications in cybersecurity and other areas.

ORNL quantum researchers Joseph Lukens, Pavel Lougovski, Brian Williams, and Nicholas Peters—along with collaborators from Purdue University and the Technological University of Pereira in Colombia—summarized results from several of their recent academic papers in a special issue of the Optical Society’s Optics & Photonics News, which showcased some of the most significant results from optics-related research in 2019. Their entry was one of 30 selected for publication from a pool of 91.

Conventional computer “bits” have a value of either 0 or 1, but quantum bits, called “qubits,” can exist in a superposition of quantum states labeled 0 and 1. This ability makes quantum systems promising for transmitting, processing, storing, and encrypting vast amounts of information at unprecedented speeds.

IBM and the University of Tokyo will form the Japan – IBM Quantum Partnership, a broad national partnership framework in which other universities, industry, and government can engage. The partnership will have three tracks of engagement: one focused on the development of quantum applications with industry; another on quantum computing system technology development; and the third focused on advancing the state of quantum science and education.

Under the agreement, an IBM Q System One, owned and operated by IBM, will be installed in an IBM facility in Japan. It will be the first installation of its kind in the region and only the third in the world following the United States and Germany. The Q System One will be used to advance research in quantum algorithms, applications and software, with the goal of developing the first practical applications of quantum computing.

IBM and the University of Tokyo will also create a first-of-a-kind quantum system technology center for the development of hardware components and technologies that will be used in next generation quantum computers. The center will include a laboratory facility to develop and test novel hardware components for quantum computing, including advanced cryogenic and microwave test capabilities.