Superior qubits key to rapid increase in power.

Physicists at the National Institute of Standards and Technology have boosted their control of the fundamental properties of molecules at the quantum level by linking or “entangling” an electrically charged atom and an electrically charged molecule, showcasing a way to build hybrid quantum information systems that could manipulate, store and transmit different forms of data.

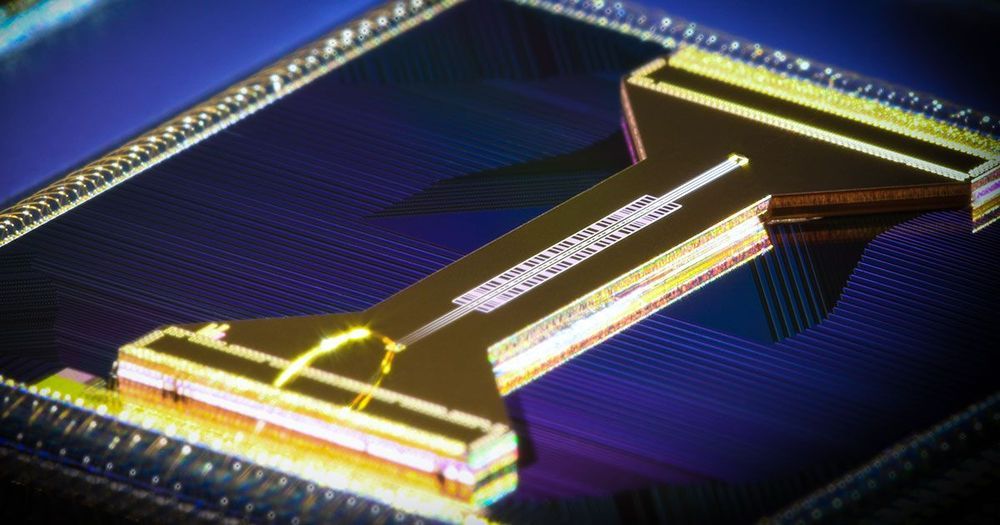

Described in a Nature paper posted online May 20, the new NIST method could help build large-scale quantum computers and networks by connecting quantum bits (qubits) based on otherwise incompatible hardware designs and operating frequencies. Mixed-platform quantum systems could offer versatility like that of conventional computer systems, which, for example, can exchange data among an electronic processor, an optical disc, and a magnetic hard drive.

The NIST experiments successfully entangled the properties of an electron in the atomic ion with the rotational states of the molecule so that measurements of one particle would control the properties of the other. The research builds on the same group’s 2017 demonstration of quantum control of a molecule, which extended techniques long used to manipulate atoms to the more complicated and potentially more fruitful arena offered by molecules, composed of multiple atoms bonded together.

To many developers, quantum computing may still feel like a futuristic technology shrouded in mystery and surrounded by hype. It’s some mystic dance of 1s and 0s that will enable some calculations in mere hours that today would take the lifetime of the universe to compute. It’s somehow related to a cat that may or may not be dead in a box.

The question we hear most often from developers is how do you make sense of what’s real and get started?

Over the last year, we’ve been working with you, the pioneering community of quantum developers, to understand what all developers will need on the path to scalable quantum computing. You’ve told us that you want to learn more about where quantum could impact your business today, to have easier ways to start writing quantum code, and to run applications against a range of quantum and classical hardware.

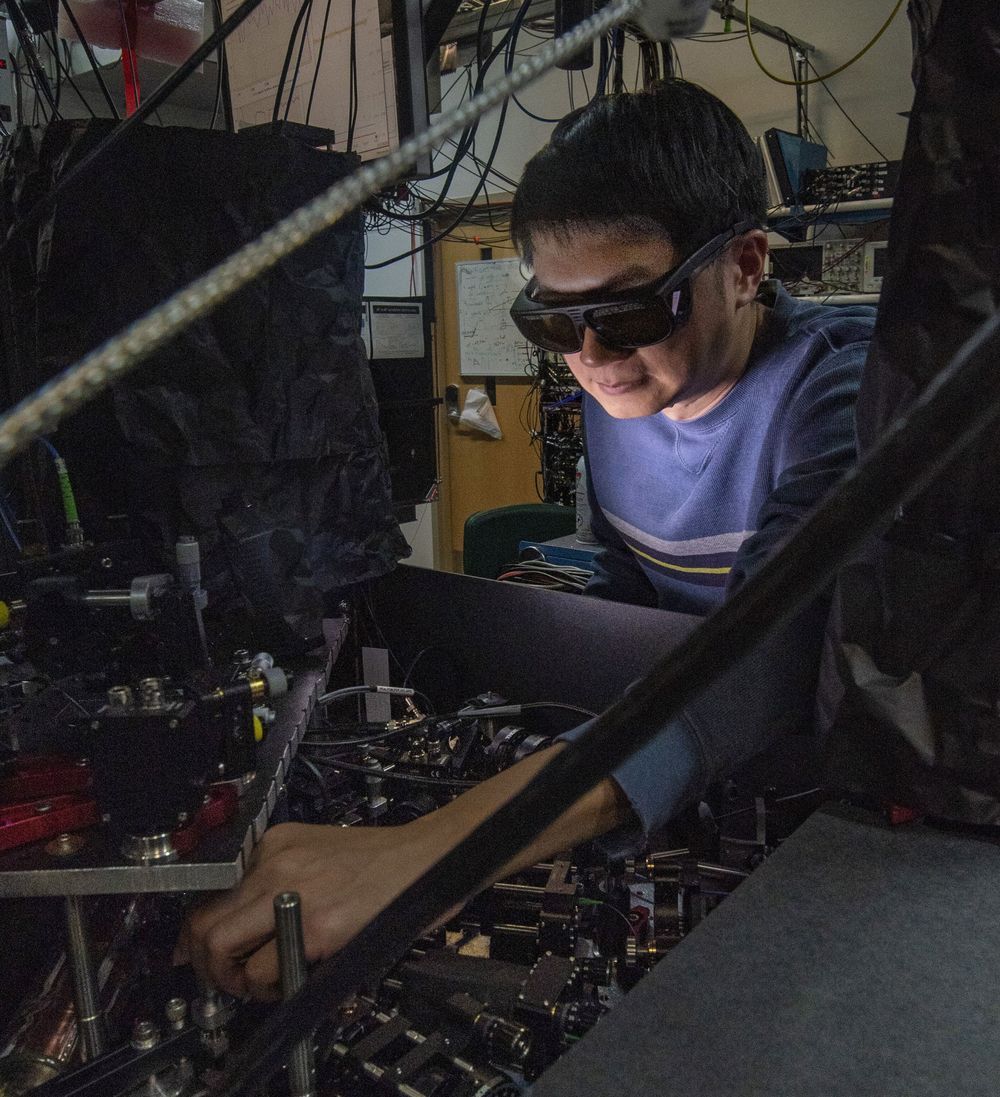

Scientists are using light waves to accelerate supercurrents and access the unique properties of the quantum world, including forbidden light emissions that one day could be applied to high-speed, quantum computers, communications and other technologies.

The scientists have seen unexpected things in supercurrents—electricity that moves through materials without resistance, usually at super cold temperatures—that break symmetry and are supposed to be forbidden by the conventional laws of physics, said Jigang Wang, a professor of physics and astronomy at Iowa State University, a senior scientist at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Ames Laboratory and the leader of the project.

Wang’s lab has pioneered use of light pulses at terahertz frequencies- trillions of pulses per second—to accelerate electron pairs, known as Cooper pairs, within supercurrents. In this case, the researchers tracked light emitted by the accelerated electrons pairs. What they found were “second harmonic light emissions,” or light at twice the frequency of the incoming light used to accelerate electrons.

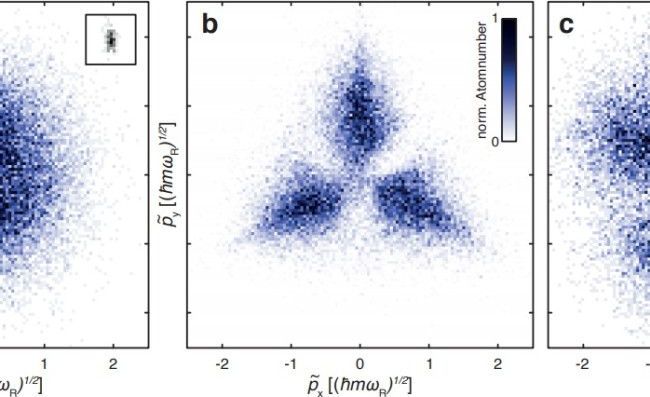

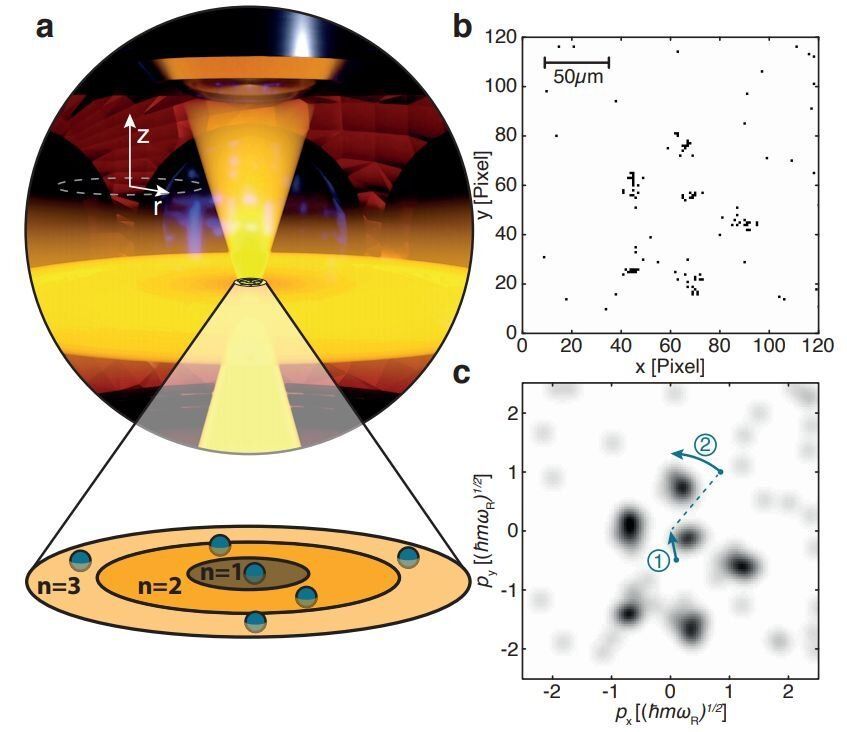

A team of researchers at Heidelberg University has succeeded in building an apparatus that allowed them to observe Pauli crystals for the first time. They have written a paper describing their efforts and have uploaded it to the arXiv preprint server.

The Pauli exclusion principle is quite simple: It asserts that no two fermions can have the same quantum number. But as with many principles in physics, this simple assertion has had a profound impact on quantum mechanics. Looking more closely at the principle reveals that it also suggests that no two fermions can occupy the same quantum state. And that means that electrons must have different orbits around a nucleus, and by extension, it explains why atoms have volume. This understanding of the self-ordering of fermions has led to other findings—for instance, that they should form crystals with a specific geometry, which are now known as Pauli crystals. When this observation was first made, it was understood that such crystal formation could only happen under unique circumstances. In this new effort, the researchers have resolved the circumstances, and in so doing, have built an apparatus that allowed them to observe Pauli crystals for the first time.

The work involved a setup that included lasers that were able to trap a cloud of lithium-6 atoms supercooled to their lower energy state, forcing them to adhere to the exclusion principle, in a one-atom thick flat layer. The team then used a technique that allowed them to photograph the atoms when they were in a particular given state—and only those atoms. They then used the camera to take 20,000 pictures, but used only those that showed the right number of atoms—-indicating that they were adhering to the Pauli exclusion principle. Next, the team processed the remaining images to remove the impact of overall momentum in the atom cloud, rotated them properly, and then superimposed thousands of them, revealing the momentum distribution of the individual atoms —that was the point at which crystal structures began to emerge in the photographs, just as was predicted by theory. The researchers note that their technique could also be used to study other effects related to fermion-based gases.

It sounds like a riddle: What do you get if you take two small diamonds, put a small magnetic crystal between them and squeeze them together very slowly?

The answer is a magnetic liquid, which seems counterintuitive. Liquids become solids under pressure, but not generally the other way around. But this unusual pivotal discovery, unveiled by a team of researchers working at the Advanced Photon Source (APS), a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility at DOE’s Argonne National Laboratory, may provide scientists with new insight into high-temperature superconductivity and quantum computing.

Though scientists and engineers have been making use of superconducting materials for decades, the exact process by which high-temperature superconductors conduct electricity without resistance remains a quantum mechanical mystery. The telltale signs of a superconductor are a loss of resistance and a loss of magnetism. High-temperature superconductors can operate at temperatures above those of liquid nitrogen (−320 degrees Fahrenheit), making them attractive for lossless transmission lines in power grids and other applications in the energy sector.

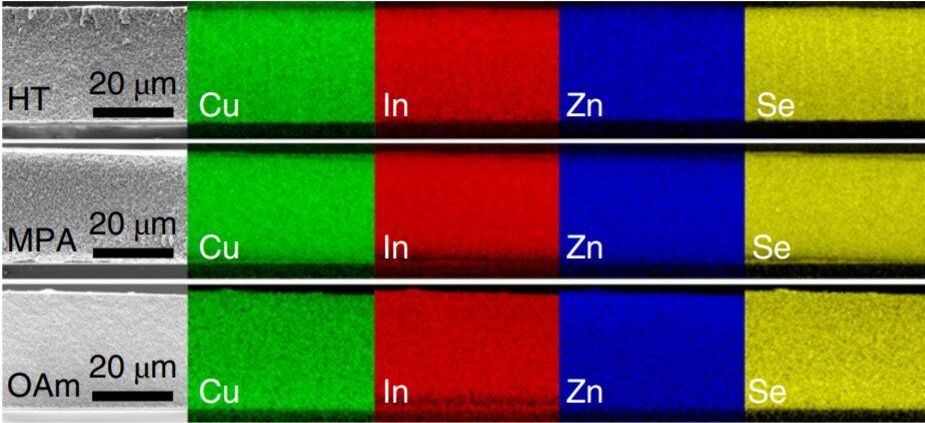

Novel quantum dot solar cells developed at Los Alamos National Laboratory match the efficiency of existing quantum-dot based devices, but without lead or other toxic elements that most solar cells of this type rely on.

“This quantum-dot approach shows great promise for a new type of toxic-element-free, inexpensive solar cells that exhibit remarkable defect tolerance,” said Victor Klimov, a physicist specializing in semiconductor nanocrystals at Los Alamos and lead author of the report featured on the cover of the journal Nature Energy.

Not only did the researchers demonstrate highly efficient devices, they also revealed the mechanism underlying their remarkable defect tolerance. Instead of impeding photovoltaic performance, the defect states in copper indium selenide quantum dots actually assist the photoconversion process.

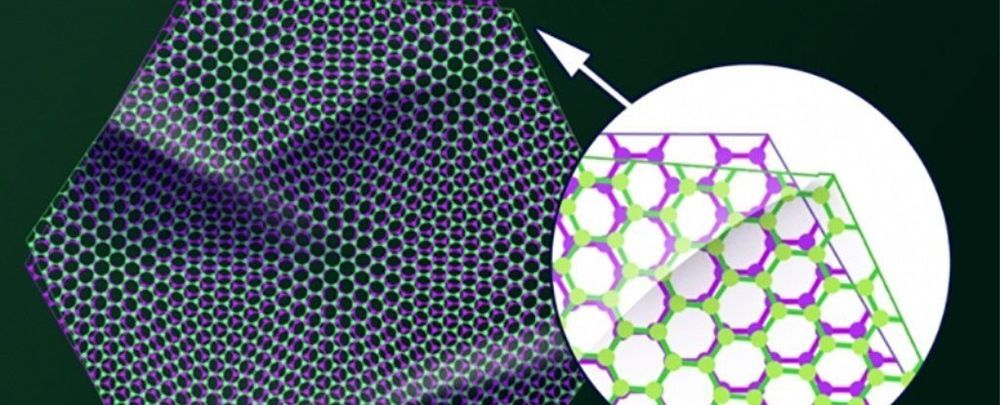

Graphene has already proven itself to be a weird and wonderful material in many different ways, but its properties get even more unusual and exotic when it’s twisted – and two new studies have given scientists a much closer look at this intriguing phenomenon.

When two sheets of graphene are put together at slightly different angles, the resulting material becomes either very effective at conducting electricity, or very effective at blocking it. It’s known as ‘magic-angle’ twisted graphene, and knowing more about how and why this happens could lead to advances in high-temperature superconductors and quantum computing.

Now for the first time, scientists have mapped out a twisted graphene structure in its entirety, and at a very high resolution. They’ve also been able to get ‘graphene twistronics’ working with four layers of graphene as well as just two.

DARPA has selected seven university and industry teams for the first phase of the Optimization with Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum devices (ONISQ) program. Phase 1 of the program began in March and will last 18 months.

ONISQ aims to exploit quantum information processing before universal fault-tolerant quantum computers are realized, which isn’t expected for many years. The program is pursuing a hybrid concept that combines intermediate-sized quantum devices (hundreds to thousands of quantum bits, or qubits) with classical computing systems to solve a particularly challenging set of problems known as combinatorial optimization.

ONISQ seeks to demonstrate a quantitative advantage of quantum information processing by leapfrogging the performance of classical-only systems in solving optimization challenges. If successful, ONISQ could be applied to optimization problems of interest to defense and commercial industry, such as global logistics management, electronics manufacturing, and protein-folding.