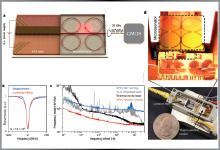

Optical frequency synthesizers – systems that output laser beams at precise and stable frequencies – have proven extremely valuable in a variety of scientific endeavors, including space exploration, gas sensing, control of quantum systems, and high-precision light detection and ranging (LIDAR). While they provide unprecedented performance, the use of optical frequency synthesizers has largely been limited to laboratory settings due to the cost, size, and power requirements of their components. To reduce these obstacles to widespread use, DARPA launched the Direct On-Chip Digital Optical Synthesizer (DODOS) program in 2014. Key to the program is the miniaturization of necessary components and their integration into a compact module, enabling broader deployment of the technology while unlocking new applications.

To accomplish its goals, DODOS is leveraging advances in microresonators – tiny structures that store light in microchips – to produce optical frequency combs in compact integrated packages. Frequency combs earn their name by converting a single-color input laser beam into a sequence of many additional colors that are evenly spaced and resemble a hair comb. With a sufficiently wide array of comb “teeth,” innovative techniques to eliminate noise become possible that make combs an attractive option for systems needing precise frequency references.

Until recently, creating frequency combs from microresonators was a complex affair that required sophisticated control schemes, dedicated circuitry, and oftentimes, an expert scientist to carefully observe and fine-tune the operation. This is primarily due to the sensitive properties of the microresonator, which needs the perfect amount of light at a special operating frequency – or color – to be provided by an input laser in order for the comb to turn on and even then, producing a coherent or stable comb state could not be guaranteed every time.