Researchers announced the achievement of an important milestone on the road to nuclear fusion and we’re at the threshold of fusion ignition.

Quick – define common sense

Despite being both universal and essential to how humans understand the world around them and learn, common sense has defied a single precise definition. G. K. Chesterton, an English philosopher and theologian, famously wrote at the turn of the 20th century that “common sense is a wild thing, savage, and beyond rules.” Modern definitions today agree that, at minimum, it is a natural, rather than formally taught, human ability that allows people to navigate daily life.

Common sense is unusually broad and includes not only social abilities, like managing expectations and reasoning about other people’s emotions, but also a naive sense of physics, such as knowing that a heavy rock cannot be safely placed on a flimsy plastic table. Naive, because people know such things despite not consciously working through physics equations.

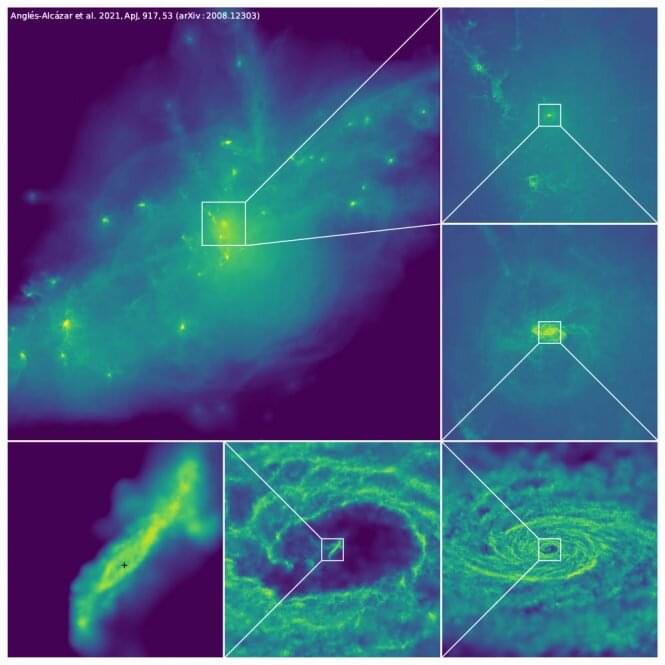

At the center of galaxies, like our own Milky Way, lie massive black holes surrounded by spinning gas. Some shine brightly, with a continuous supply of fuel, while others go dormant for millions of years, only to reawaken with a serendipitous influx of gas. It remains largely a mystery how gas flows across the universe to feed these massive black holes.

UConn Assistant Professor of Physics Daniel Anglés-Alcázar, lead author on a paper published today in The Astrophysical Journal, addresses some of the questions surrounding these massive and enigmatic features of the universe by using new, high-powered simulations.

“Supermassive black holes play a key role in galaxy evolution and we are trying to understand how they grow at the centers of galaxies,” says Anglés-Alcázar. “This is very important not just because black holes are very interesting objects on their own, as sources of gravitational waves and all sorts of interesting stuff, but also because we need to understand what the central black holes are doing if we want to understand how galaxies evolve.”

Determining if particular extreme hot or cold spells were caused by climate change could be made easier by a new mathematical method.

The statistical method, developed by physicists at the University of Reading and Uppsala University in Sweden, looks at the characteristics, or “fingerprints,” of a specific extreme weather event of interest, like a heatwave, in order to ascertain whether it can be attributed to natural climate variability of the climate or is a unique product of global warming.

The method also allows predictions to be made about how likely extreme climate events will be in the future.

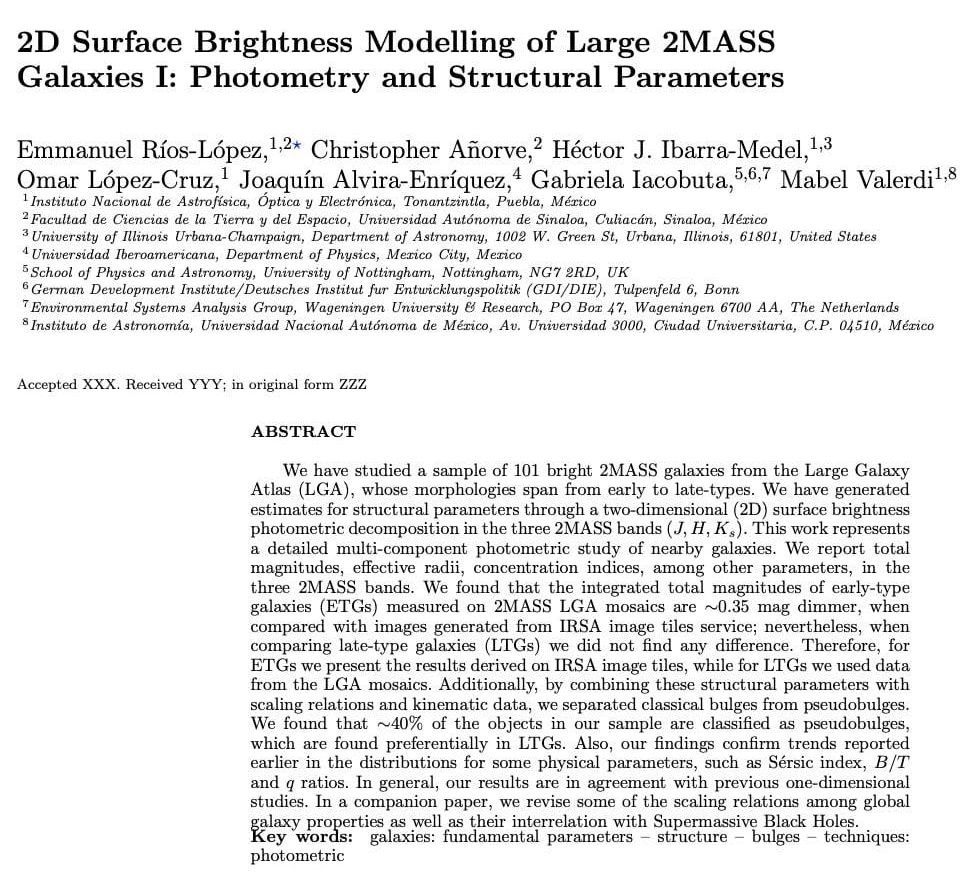

Congratulations to Dr. Emmanuel Ríos López and her co-advisor Dr. X’opher Añorve and to our collaborators, Dr. Hector Javier Ibarra Medel, the Dr. Mabel Valerdi, the Dr. Gabriela Ileana Tudorica Iacobuta and the lng. Physics. Joaquin Alvira Enriquez. Three generations of summer students (VICI): Alvira-Enriquez, Valerdi and Iacobuta. Three generations of PhD students: Añorve, Ibarra-Medel and Rios-Lopez.

In this work we analyzed a sample of 101 brilliant galaxies using a two-dimensional decomposition of the shallow shine. This work serves to explore the formation of galaxies and their relationship with the supermassive holes black houses in their cores. We fixed some errors that the original sample came dragging.

We are grateful to Prof. Thomas Jarrett and Dr. Chien Peng for helping us along the generation of the work. We are standing on their shoulders, Prof. generated the Large Galaxy Atlas and Dr. Peng gave us GALFIT the best software for galaxy 2D surface brightness analysis.

We appreciate the sponsorship of INAOE, Conacyt„ Academia Mexicana de Ciencias and the Verano de la Investigación Científica del INAOE.

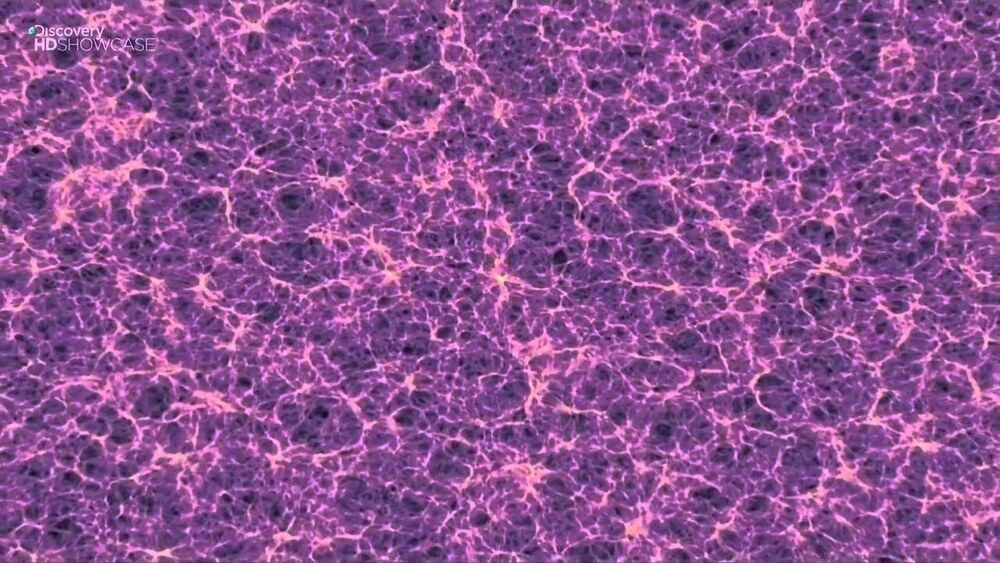

But a team of physicists is proposing a radical idea: Instead of forming black holes through the usual death-of-a-massive-start route, giant dark matter halos directly collapsed, forming the seeds of the first great black holes.

Supermassive black holes (SMBHs) appear early in the history of the universe, as little as a few hundred million years after the Big Bang. That rapid appearance poses a challenge to conventional models of SMBH birth and growth because it doesn’t look like there can be enough time for them to grow so massive so quickly.

“Physicists are puzzled why SMBHs in the early universe, which are located in the central regions of dark matter halos, grow so massively in a short time,” said Hai-Bo Yu, an associate professor of physics and astronomy at UC Riverside, who led a study of SMBH formation that appeared in Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Stars scattered throughout the cosmos look different, but they may be more alike than once thought, according to Rice University researchers.

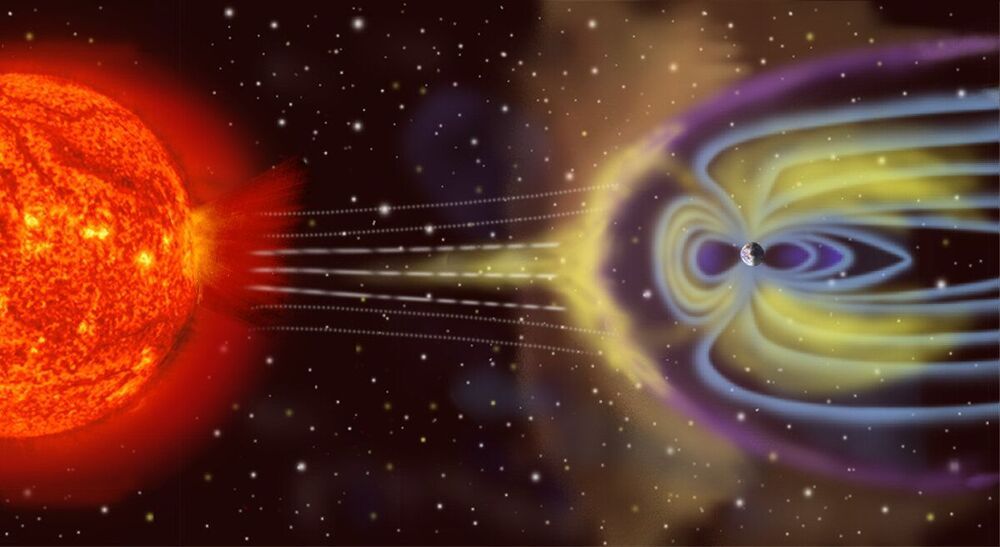

New modeling work by Rice scientists shows that “cool” stars like the sun share the dynamic surface behaviors that influence their energetic and magnetic environments. This stellar magnetic activity is key to whether a given star hosts planets that could support life.

The work by Rice postdoctoral researcher Alison Farrish and astrophysicists David Alexander and Christopher Johns-Krull appears in a published study in The Astrophysical Journal. The research links the rotation of cool stars with the behavior of their surface magnetic flux, which in turn drives the star’s coronal X-ray luminosity, in a way that could help predict how magnetic activity affects any exoplanets in their systems.

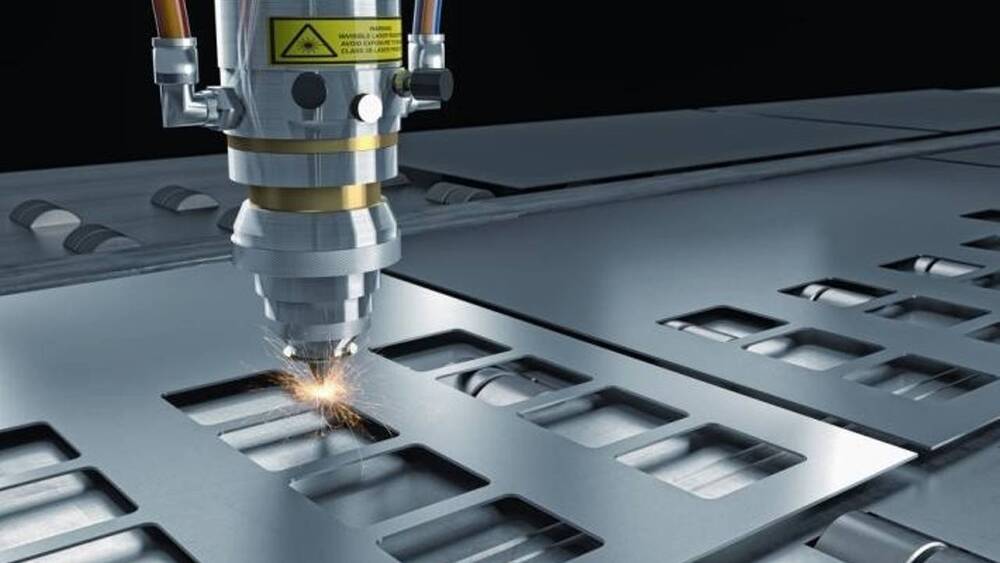

Three scientists on Tuesday won the Nobel Physics Prize, including the first woman to receive the prestigious award in 55 years, for inventing Chirped-pulse amplification, or CPA. The 9-million-Swedish-kronor award (about $1 million) will be doled out to Arthur Ashkin of Bell Laboratories in Holmdel, N.J., Gérard Mourou of École Polytechnique in Palaiseau, France, and Donna Strickland of the University of Waterloo in Canada. This is a technique for creating ultrashort, yet extremely high-energy laser pulses necessary in a variety of applications. It is remarkable what can be achieved with lasers in research and in applications, and there are many good reasons for it, including their coherence, frequency stability, and controllability, but for some applications, the thing that really matters is raw power. Article by Dr. Olivier Alirol, Physicist, Resonance Science Foundation Research Scientist.

Circa 2016

Scientists and engineers since the 1940s have been toying with the idea of building self-replicating machines, or von Neumann machines, named for John von Neumann. With recent advances in 3D printing (including in zero gravity) and machine learning AI, it seems like self-replicating machines are much more feasible today. In the 21st century, a tantalizing possibility for this technology has emerged: sending a space probe out to a different star system, having it mine resources to make a copy of itself, and then launching that one to yet another star system, and on and on and on.

As a wild new episode of PBS’s YouTube series Space Time suggests, if we could send a von Neumann probe to another star system—likely Alpha Centauri, the closest to us at about 4.4 light years away—then that autonomous spaceship could land on a rocky planet, asteroid, or moon and start building a factory. (Of course, it’d probably need a nuclear fusion drive, something we still need to develop.)

That factory of autonomous machines could then construct solar panels, strip mine the world for resources, extract fuels from planetary atmospheres, build smaller probes to explore the system, and eventually build a copy of the entire von Neumann spacecraft to send off to a new star system and repeat the process. It has even been suggested that such self-replicating machines could build a Dyson sphere to harness energy from a star or terraform a planet for the eventual arrival of humans.