If physicists do find that gravitational waves have travelled through dimensions other than the four we live in, it will be the start of a revolution in physics. But how close are we really?

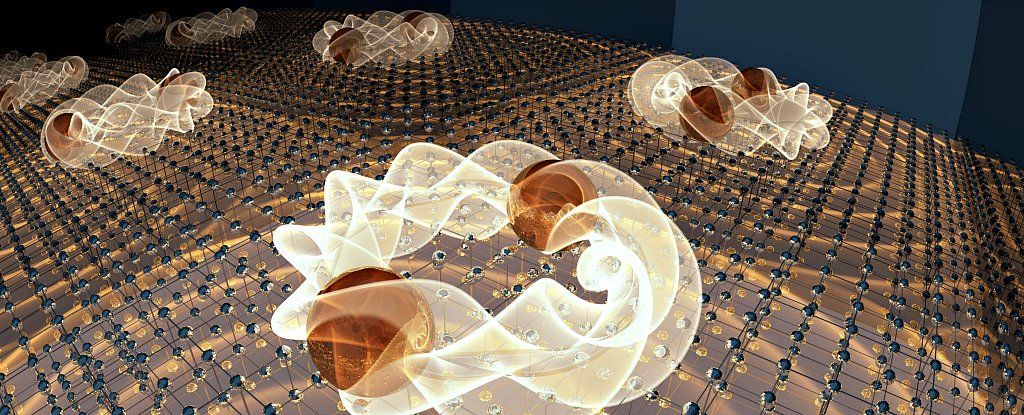

One of the ultimate goals of modern physics is to unlock the power of superconductivity, where electricity flows with zero resistance at room temperature.

Progress has been slow, but physicists have just made an unexpected breakthrough. They’ve discovered a superconductor that works in a way no one’s ever seen before — and it opens the door to a whole world of possibilities not considered until now.

In other words, they’ve identified a brand new type of superconductivity.

Scientists have made the most precise measurement of antimatter yet, and the results only deepen the mystery of why life, the universe, and everything in it exists.

The new measurements show that, to an incredibly high degree of precision, antimatter and matter behave identically.

Yet those new measurements can’t answer one of the biggest questions in physics: Why, if equal parts matter and antimatter were formed during the Big Bang, is our universe today made up of matter?

Mach Effect Gravity Assist (MEGA) drive propulsion is based on peer-reviewed, technically credible physics. Mach effects are transient variations in the rest masses of objects that simultaneously experience accelerations and internal energy changes. They are predicted by standard physics where Mach’s principle applies as discussed in peer-reviewed papers spanning 20 years and a recent book, Making Starships and Stargates: the Science of Interstellar Transport and Absurdly Benign Wormholes published in 2013 by Springer-Verlag.

Above – Graphic depiction of Mach Effect for in-space propulsion: Interstellar mission Credits: J. Woodward.

A team of U.S. and German scientists has used a system of large magnetic “trim” coils designed and delivered by the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) to achieve high performance in the latest round of experiments on the Wendelstein 7-X (W7-X) stellarator. The German machine, the world’s largest and most advanced stellarator, is being used to explore the scientific basis for fusion energy and test the suitability of the stellarator design for future fusion power plants. Such plants would use fusion reactions such as those that power the sun to create an unlimited energy source on Earth.

The new experiments amply demonstrated the ability of the five copper trim coils and their sophisticated control system, whose operation is led on-site by PPPL physicist Samuel Lazerson, to improve the overall performance of the W7-X. “What’s exciting about this is that the trim coils and Sam’s leadership are producing scientific understanding that will help to optimize future stellarators,” said PPPL physicist Hutch Neilson, who oversees the laboratory’s collaboration on the W7-X with the Max Planck Institute of Plasma Physics, which built the machine and now hosts the international team investigating the behavior of plasmas confined in its unique magnetic configuration.

Stellarators are twisty, doughnut-shaped facilities whose configuration contrasts with the smoothly doughnut-shaped facilities called tokamaks that are more widely used. A major advantage of stellarators is their ability to operate continuously with low input power to sustain the plasma without plasma disruptions—a risk that tokamaks face—enabling the facilities to operate efficiently in steady state. A disadvantage is that the twisting stellarator geometry is more complex to design and build.

Scientists are no strangers to healthy debate. You need criticism to strengthen your ideas, and when debate is done right, both parties leave knowing more than they did when they started. But there are some things that will just make a scientist mad. One of those things? Saying their scientific theory isn’t scientific. That’s what a trio of physicists did in a 2017 article they published in Scientific American, which stated that the idea of an expanding universe simply isn’t testable. The response from other physicists? Oh, it’s on.

Without an actual discovery, it can be difficult to convince us laypeople that there’s really such a thing as “dark matter.” It seems to interact with our universe solely through gravity, and no experiment has detected it here on Earth yet. So what if there’s an explanation to what’s causing the dark matter’s using physics that already exists, like Higgs bosons and black holes?

A team of three European physicists has made what could be seen as a controversial statement: “The existence of dark matter might not require physics beyond the standard model.” It’s still just a hypothesis as the hunt for dark matter continues, but it’s an interesting thought to digest.

First, you might be wondering what I’m talking about at all. You only experience regular matter in your day-to-day life—it’s what makes up every planet, star, and galaxy. But astronomical observations imply that there’s gravity from six times more matter in the universe, stuff we can’t see with our eyes or instruments, called dark matter. As of yet, lots of experiments have tried and failed to identify the source of this gravity.

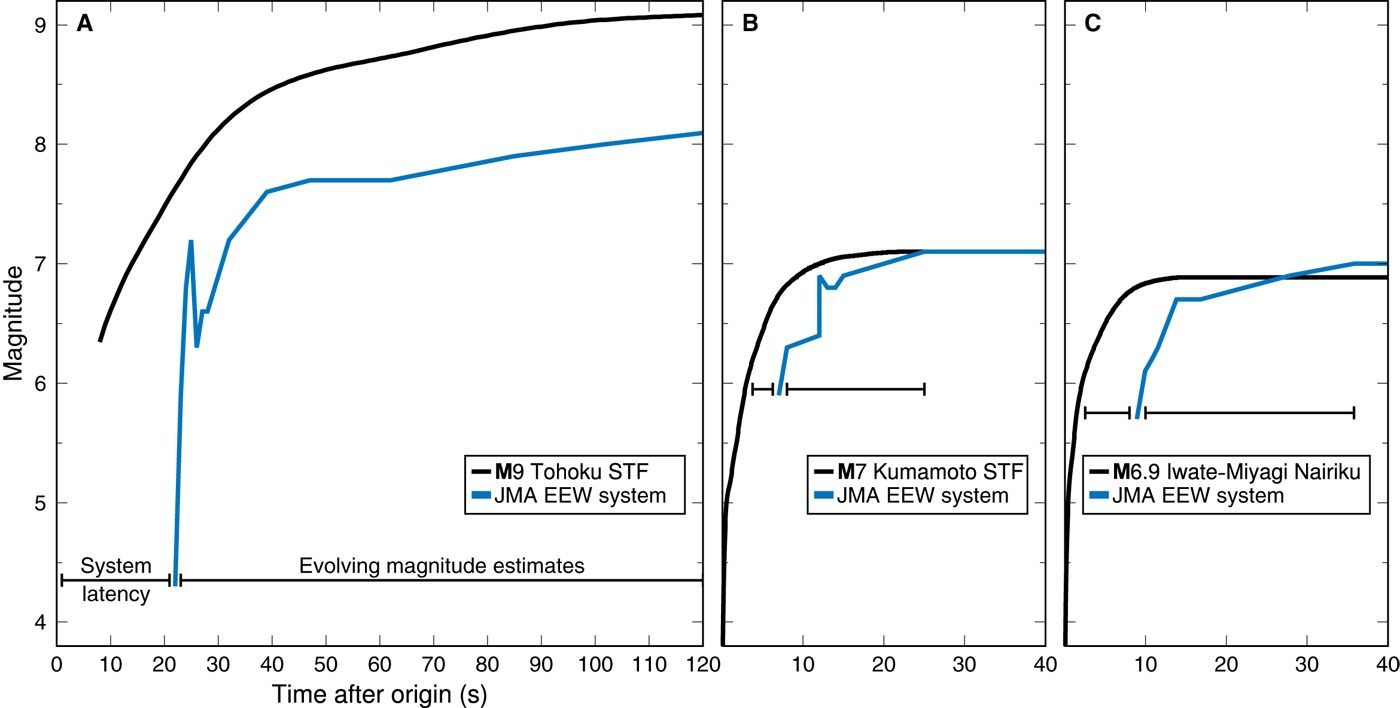

The basic physics of earthquakes is such that strong ground motion cannot be expected from an earthquake unless the earthquake itself is very close or has grown to be very large. We use simple seismological relationships to calculate the minimum time that must elapse before such ground motion can be expected at a distance from the earthquake, assuming that the earthquake magnitude is not predictable. Earthquake early warning (EEW) systems are in operation or development for many regions around the world, with the goal of providing enough warning of incoming ground shaking to allow people and automated systems to take protective actions to mitigate losses. However, the question of how much warning time is physically possible for specified levels of ground motion has not been addressed. We consider a zero-latency EEW system to determine possible warning times a user could receive in an ideal case. In this case, the only limitation on warning time is the time required for the earthquake to evolve and the time for strong ground motion to arrive at a user’s location. We find that users who wish to be alerted at lower ground motion thresholds will receive more robust warnings with longer average warning times than users who receive warnings for higher ground motion thresholds. EEW systems have the greatest potential benefit for users willing to take action at relatively low ground motion thresholds, whereas users who set relatively high thresholds for taking action are less likely to receive timely and actionable information.

Earthquake early warning (EEW) systems rapidly detect and characterize ongoing earthquakes in real time to provide advance warnings of impending ground motion. They use the information contained in the early parts of the typically low-amplitude ground motion waveforms to estimate the ensuing and potentially large-amplitude ground motion. Because EEW alert information can be transmitted faster than seismic wave propagation speed, such ground motion warnings may arrive at a target site before the strong shaking itself, thereby providing invaluable time for both people and automated systems to take actions to mitigate earthquake-related injury and losses. These actions might range from simple procedures like warning people to get themselves to a safe location to complex automated procedures like halting airport takeoffs and landings.