A trio of researchers with The University of Hong Kong, Academia Sinica Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics in Taiwan and Northwestern University in the U.S., has come up with an alternative theory to explain how some stellar-mass black holes can grow bigger than others. In their paper published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, Shu-Xu Yi, K.S. Cheng and Ronald Taam describe their theory and how it might work.

Since the initial detection of gravitational waves three years ago, five more detections have been observed—and five of the total have been traced back to emissions created by two stellar-mass black holes merging. The sixth was attributed to neutron stars merging. As part of their studies of such detections, space researchers have been surprised by the size of the stellar-mass black holes producing the gravity waves—they were bigger than other stellar-mass black holes. Their larger size has thus far been explained by the theory that they grew larger because they began their lives as stars that contained very small amounts of metal—stars with traces of metals would retain most of their mass because they produce weaker solar winds. In this new effort, the researchers suggest another possible way for stellar-mass black holes to grow larger than normal.

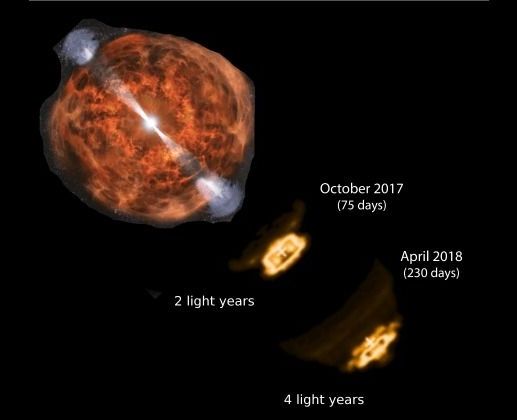

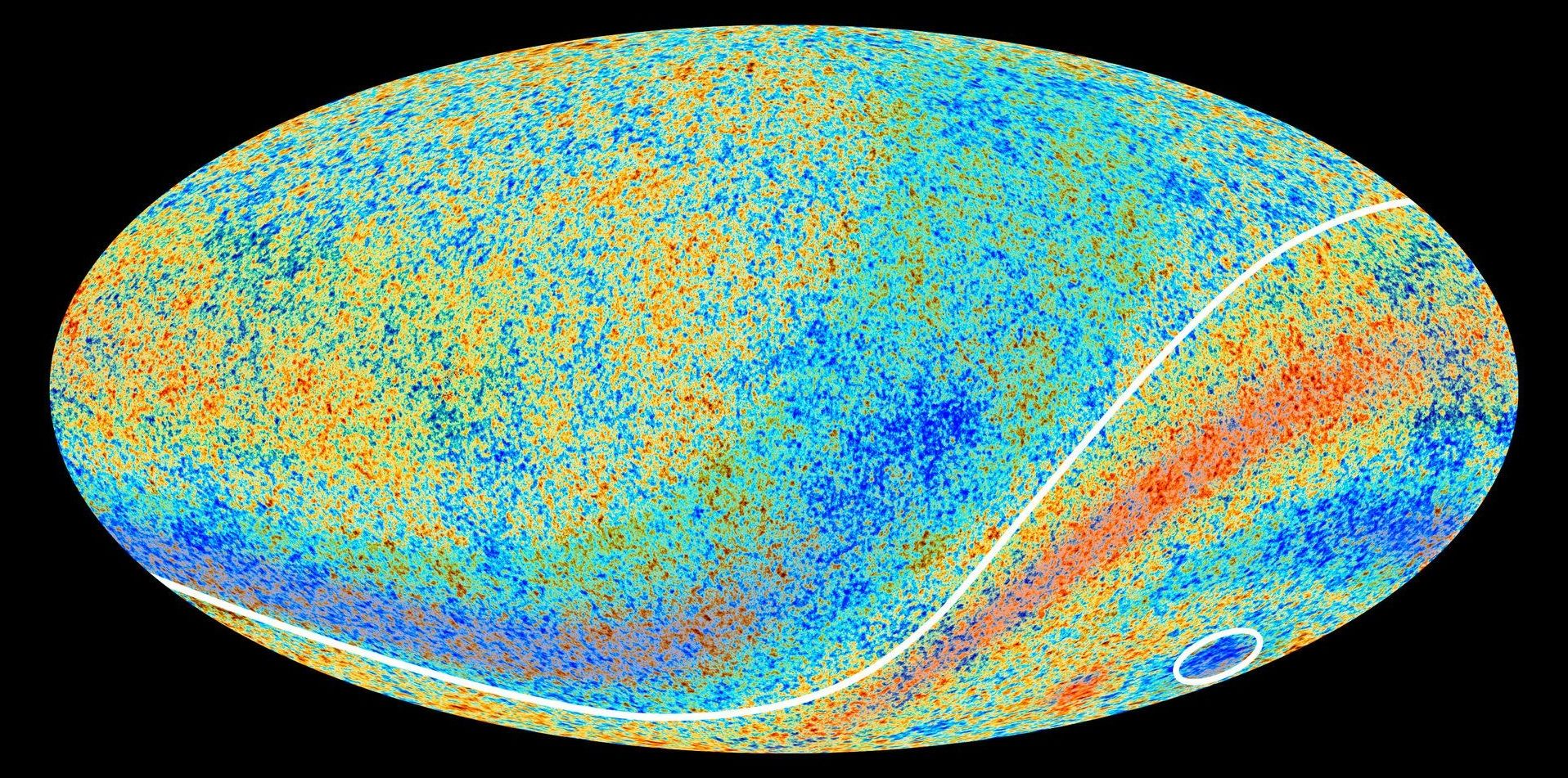

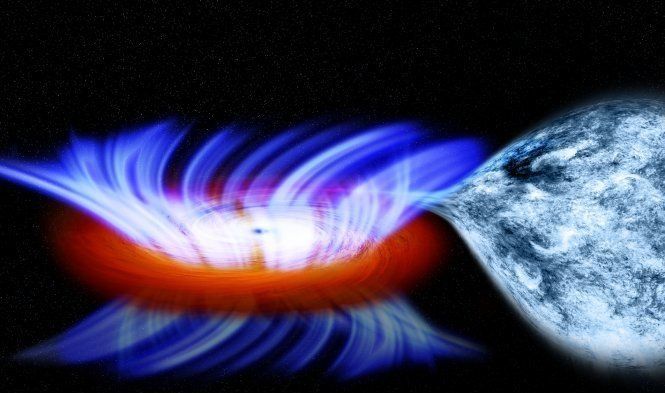

The new theory starts out by noting that some supermassive black holes at the hearts of galaxies are surrounded by a disk of gas and dust. In such galaxies, there are often stars lying just outside the disk—stars that could evolve to become stellar-mass black holes. The researchers suggest that it is possible that sometimes, pairs of these stars wind up in the disk as they evolve into black holes. Such stellar-mass black holes would pull in material from the disk, causing them to grow larger. The researchers note that if such a scenario were to play out, it is also possible that the two merging stars could wind up with a synchronized spin resulting in a stellar-mass black hole that produces more gravity waves than if the spins had not been synchronized, making them easier for researchers to spot.

Read more