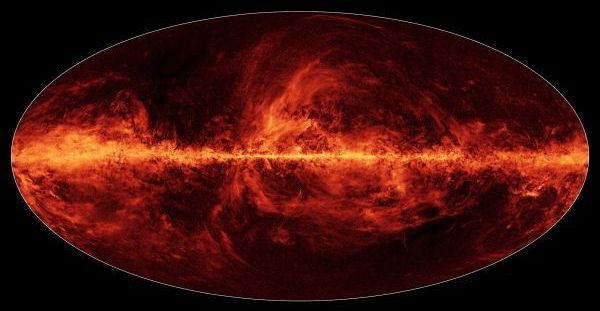

A new study on the rotation of the universe’s first light could suggest physicists need new rule-breaking subatomic particles.

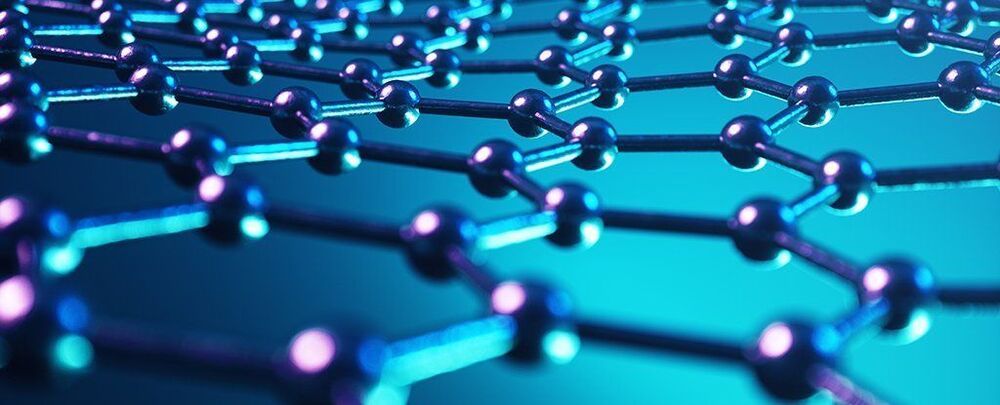

Graphene continues to dazzle us with its strength and its versatility – exciting new applications are being discovered for it all the time, and now scientists have found a way of manipulating the wonder material so that it can better filter impurities out of water.

The two-dimensional material comprised of carbon atoms has been studied as a way of cleaning up water before, but the new method could offer the most promising approach yet. It’s all down to the exploitation of what are known as van der Waals gaps: the tiny spaces that appear between 2D nanomaterials when they’re layered on top of each other.

These nanochannels can be used in a variety of ways, which scientists are now exploring, but the thinness of graphene causes a problem for filtration: liquid has to spend much of its time travelling along the horizontal plane, rather than the vertical one, which would be much quicker.

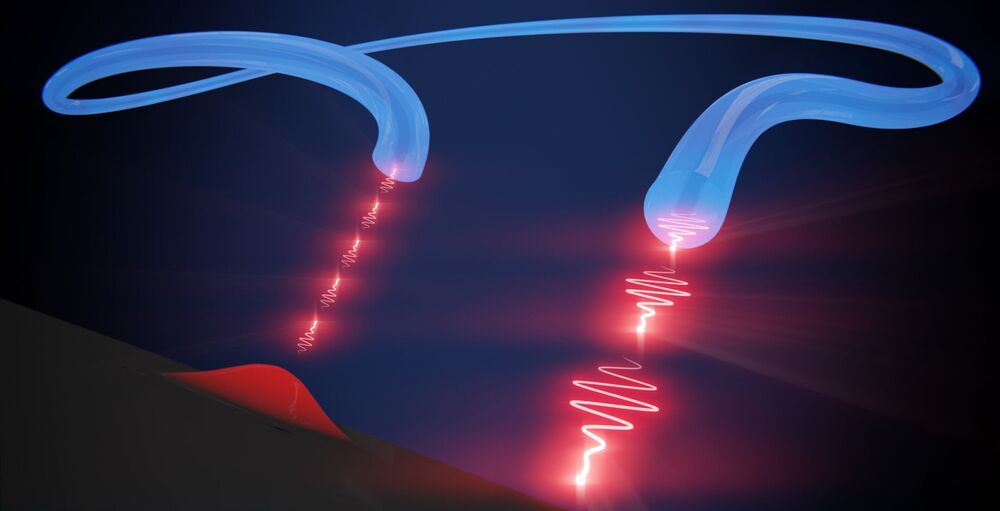

University of Stuttgart researchers developed a particle-based imaging approach that enables the spatially and temporally resolved investigation of vastly different systems such as ground-state samples, Rydberg ensembles, or cold ions immersed in quantum gases.

The microscope features an excellent time resolution allowing for both the study of dynamic processes and 3D imaging. In contrast to most quantum gas microscopes, this imaging scheme offers an enormous depth of field and is, therefore, not restricted to two-dimensional systems.

The researchers plan to use their new and powerful tool to extend our studies of cold ion-atom hybrid systems and intend to push the collision energies in these systems to the ultracold regime. Using Rydberg molecules to initialize ion-atom collisions, they envision the imaging of individual scattering events taking place in the quantum regime.

Transport processes are ubiquitous in nature but still raise many questions. The research team around Florian Meinert from the 5th Institute of Physics at the University of Stuttgart has now developed a new method that allows them to observe a single charged particle on its path through a dense cloud of ultracold atoms. The results were published in the prestigious journal Physical Review Letters and are subject in a Viewpoint of the accompanying popular science journal Physics.

Meinert‘s team uses a so-called Bose Einstein condensate (BEC) for their experiments. This exotic state of matter consists of a dense cloud of ultracold atoms. By means of sophisticated laser excitation, the researchers create a single Rydberg atom within the gas.

In this giant atom, the electron is a thousand times further away from the nucleus than in the ground state and thus only very weakly bound to the core. With a specially designed sequence of electric field pulses, the researchers snatch the electron away from the atom. The formerly neutral atom turns into a positively charged ion that remains nearly at rest despite the process of detaching the electron.

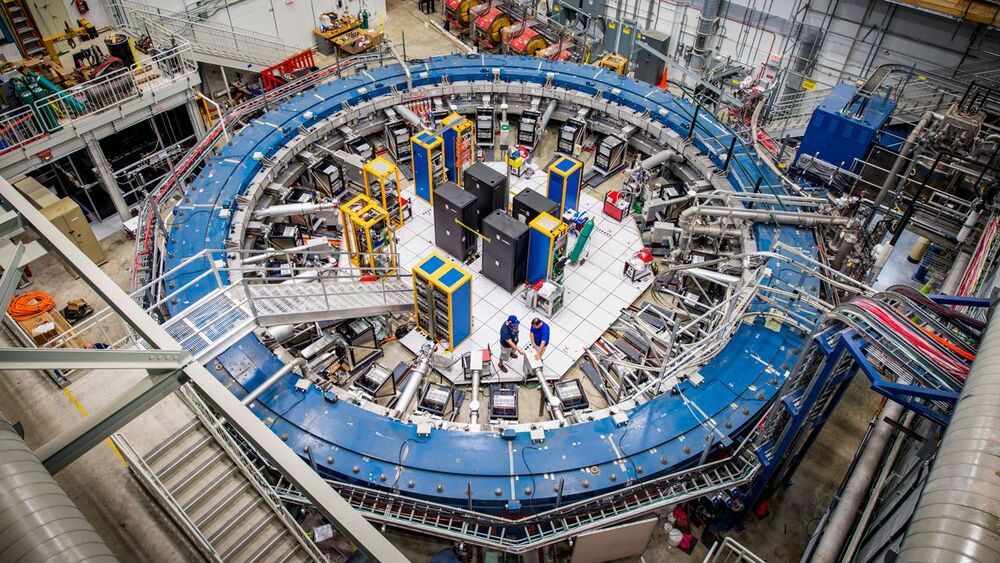

As early as March, the Muon g-2 experiment at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab) will report a new measurement of the magnetism of the muon, a heavier, short-lived cousin of the electron. The effort entails measuring a single frequency with exquisite precision. In tantalizing results dating back to 2001, g-2 found that the muon is slightly more magnetic than theory predicts. If confirmed, the excess would signal, for the first time in decades, the existence of novel massive particles that an atom smasher might be able to produce, says Aida El-Khadra, a theorist at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. “This would be a very clear sign of new physics, so it would be a huge deal.”

Locked cabinets, a secret frequency, and the curious magnetism of a particle called the muon.

Hydrogen. In theory, it’s the perfect fuel. Run it through a fuel cell and you get electricity, water vapor, and heat. Doesn’t get any more Earth friendly than that, does it? There is theory and then there is reality, starting with where one gets the hydrogen in the first place. It is one of the most abundant elements on Earth — every molecule of water has two hydrogen atoms and there is a lot of water in the world.

Then there is the whole universe of hydrocarbons from gasoline to plastics. By definition, there are hydrogen atoms in all of them and that’s the problem. Hydrogen is so reactive it bonds with everything. Getting pure hydrogen means breaking the chemical bonds that bind to other elements. Keeping it sequestered in its pure state is a whole other conundrum.

Assuming all those challenges are overcome, then comes the question of how to distribute it so it can be used to power the fuel cells in vehicles. A DC fast charging installation might cost $300000 but a hydrogen refueling station can cost $3 million. Compressing it, trucking it, and storing it all present additional hurdles to consider.

Dr. Fatima Ebrahimi designed a fusion rocket that uses magnetic fields to shoot plasma particles from a craft, which could take humans to Mars 10 times faster than current devices.