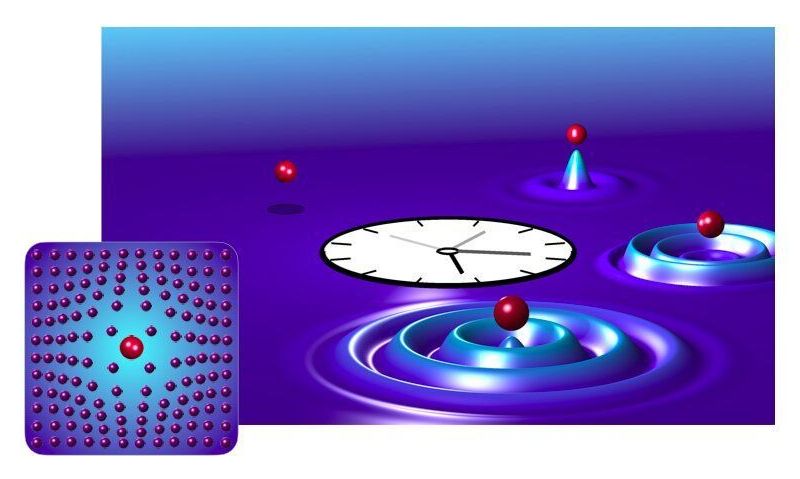

Physicists exploring the quantum world watched the birth of a quasiparticle, shedding light on the strange behavior of these strange “fake particles.”

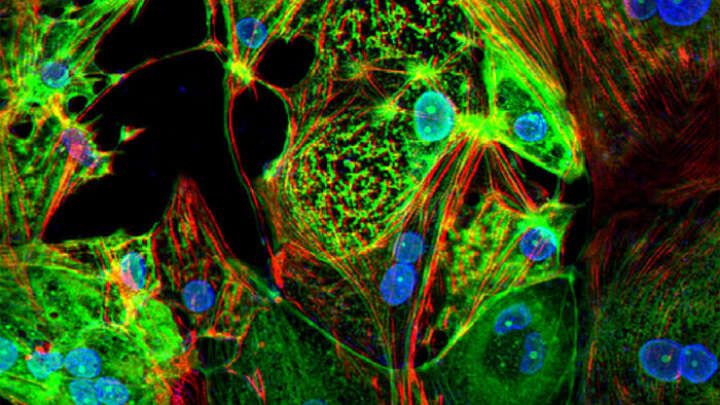

Many post COVID victims have heart issues. This is why:

A new study has discovered how the SARS-CoV-2 virus attacks and damages the heart, answering a long-standing question about mysterious heart conditions following COVID-19 infection. The results could have large implications on how to effectively treat severe infections and develop new therapies for preventing long-term damage.

Throughout the pandemic, people with severe COVID-19 infection have often displayed symptoms of heart distress. Those with underlying heart conditions are at a greater risk of severe illness if they catch it, and reports of abnormal heart rhythms (arrhythmia) in previously healthy patients with acute COVID-19 have been common.

However, exactly why this happens has eluded scientists until now. Researchers have been unsure whether the heart symptoms are a result of severe inflammation as the body reacts to the infection, or whether the virus particles themselves invade and attack heart cells.

University of Chicago researchers hunt for proposed particles that could explain quirks of the universe.

A team of researchers at the University of Chicago recently embarked on the search of a lifetime—or rather, a search for the lifetime of long-lived supersymmetric particles.

Supersymmetry is a proposed theory to expand the Standard Model of particle physics. Akin to the periodic table of elements, the Standard Model is the best description we have for subatomic particles in nature and the forces acting on them.

The recent synthesis of one-dimensional van der Waals heterostructures, a type of heterostructure made by layering two-dimensional materials that are one atom thick, may lead to new, miniaturized electronics that are currently not possible, according to a team of Penn State and University of Tokyo researchers.

Engineers commonly produce heterostructures to achieve new device properties that are not available in a single material. A van der Waals heterostructure is one made of 2D materials that are stacked directly on top of each other like Lego-blocks or a sandwich. The van der Waals force, which is an attractive force between uncharged molecules or atoms, holds the materials together.

According to Slava V. Rotkin, Penn State Frontier Professor of Engineering Science and Mechanics, the one-dimensional van der Waals heterostructure produced by the researchers is different from the van der Waals heterostructures engineers have produced thus far.

For decades, researchers assumed the cosmic rays that regularly bombard Earth from the far reaches of the galaxy are born when stars go supernova — when they grow too massive to support the fusion occurring at their cores and explode.

Those gigantic explosions do indeed propel atomic particles at the speed of light great distances. However, new research suggests even supernovae — capable of devouring entire solar systems — are not strong enough to imbue particles with the sustained energies needed to reach petaelectronvolts (PeVs), the amount of kinetic energy attained by very high-energy cosmic rays.

And yet cosmic rays have been observed striking Earth’s atmosphere at exactly those velocities, their passage marked, for example, by the detection tanks at the High-Altitude Water Cherenkov (HAWC) observatory near Puebla, Mexico. Instead of supernovae, the researchers posit that star clusters like the Cygnus Cocoon serve as PeVatrons — PeV accelerators — capable of moving particles across the galaxy at such high energy rates.

The South Pole neutrino detector saw a Glashow resonance event, a phenomenon predicted by Nobel laureate physicist Sheldon Glashow in 1960 where an electron antineutrino and an electron interact to produce a W-boson.

On December 62016, a high-energy particle called an electron antineutrino hurtled to Earth from outer space at close to the speed of light carrying 6.3 petaelectronvolts (PeV) of energy. Deep inside the ice sheet at the South Pole, it smashed into an electron and produced a particle that quickly decayed into a shower of secondary particles. The interaction was captured by a massive telescope buried in the Antarctic glacier, the IceCube Neutrino Observatory.

But Aspelmeyer and his colleagues could not declare victory quite yet: they still had to rule out the possibility that the source mass modulation was generating other forces on the test mass that would oscillate at precisely the same frequency. Periodic rocking of the table supporting the experimental apparatus, caused by recoil from the barely visible motion of the source mass, was just one of a host of confounders the researchers had to carefully quantify. In the end, they found that all known nongravitational forces would be at least 10 times smaller than the gravitational interaction.

Reaching toward Quantum Scales

Aspelmeyer believes that an improved torsion pendulum will be sensitive to gravity from masses 5000 times smaller still—lighter than a single eyelash. His ultimate goal is to experimentally test the quantum nature of gravity, a question that has perplexed physicists for nearly a century. Quantum mechanics is one of the most successful and precisely tested theories in all of science: it describes everything from the behavior of subatomic particles to the semiconductor physics that makes modern computing possible. But attempts to develop a quantum theory of gravity have repeatedly been stymied by contradictory and nonsensical predictions.

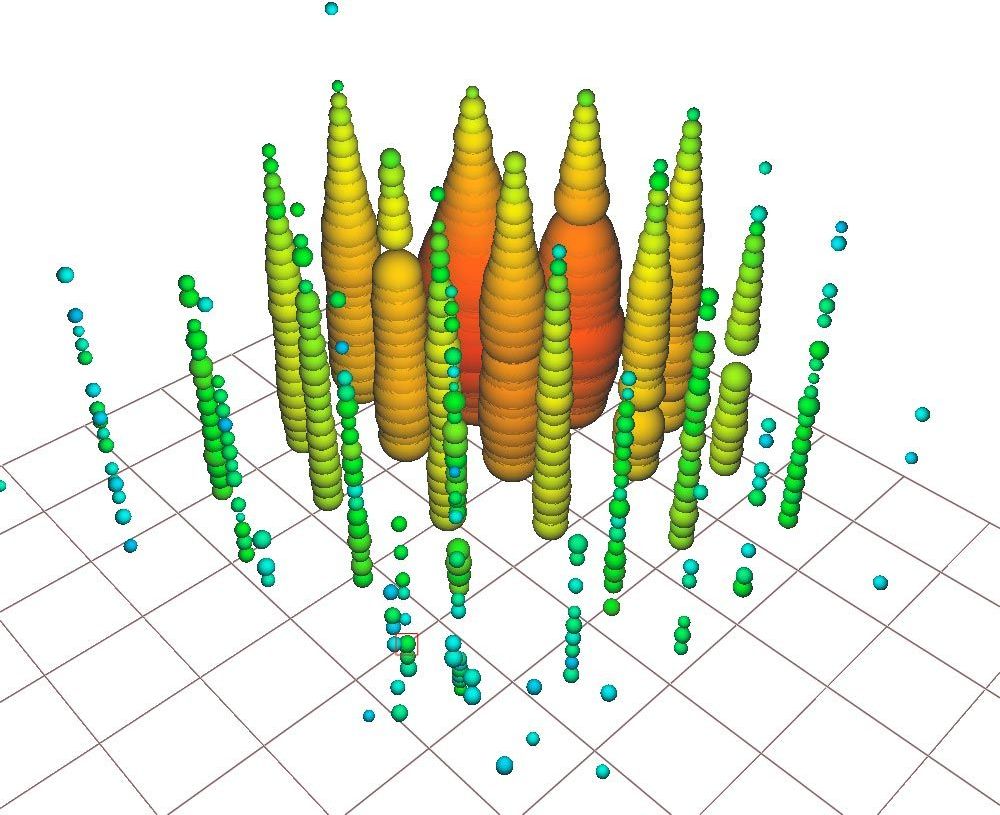

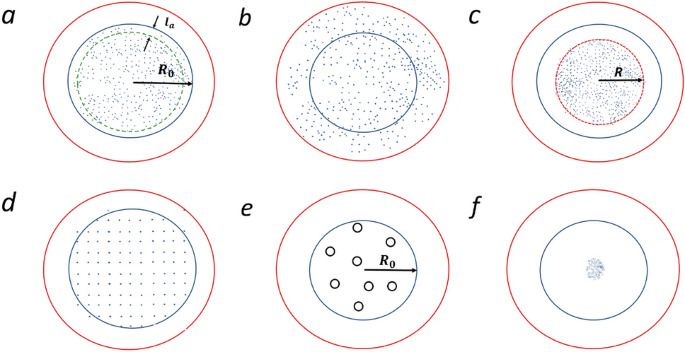

Hence, while the fast particles are abundant in molecular systems, they are practically lacking in active matter. These fast particle can overcome the attraction forces of the molecular surrounding and give rise to the gaseous phase; the lack of fast particles in active matter results in the lack of the gas, coexisting with the liquid phase. If the particle density is still larger and the repulsive forces are strong, the active matter falls into a solid phase, Fig. 1 d, where the particles mobility is suppressed.

In some range of parameters a novel swirlonic phase is formed, Fig. 1e. It is comprised of swirlons —“super-particles” with many astonishing properties which we address below. Individual active particles in swirlons perform a swirling motion around their common center. As we demonstrate in what follows, the swirlons are formed when local fluctuating force exceeds the critical force, which characterizes the ability of an active particle to move against an applied load.

Finally, for large density and very strong attractive forces a collapsed state is observed, Fig. 1 f. In the collapsed state active particle also move around the common center, however the character of the motion is rather irregular. In the present study we will focus on the gaseous, liquid and especially on the swirlonic phase.

This month is a time to celebrate. CERN has just announced the discovery of four brand new particles at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) in Geneva.

This means that the LHC has now found a total of 59 new particles, in addition to the Nobel prize-winning Higgs boson, since it started colliding protons – particles that make up the atomic nucleus along with neutrons – in 2009.

Excitingly, while some of these new particles were expected based on our established theories, some were altogether more surprising.