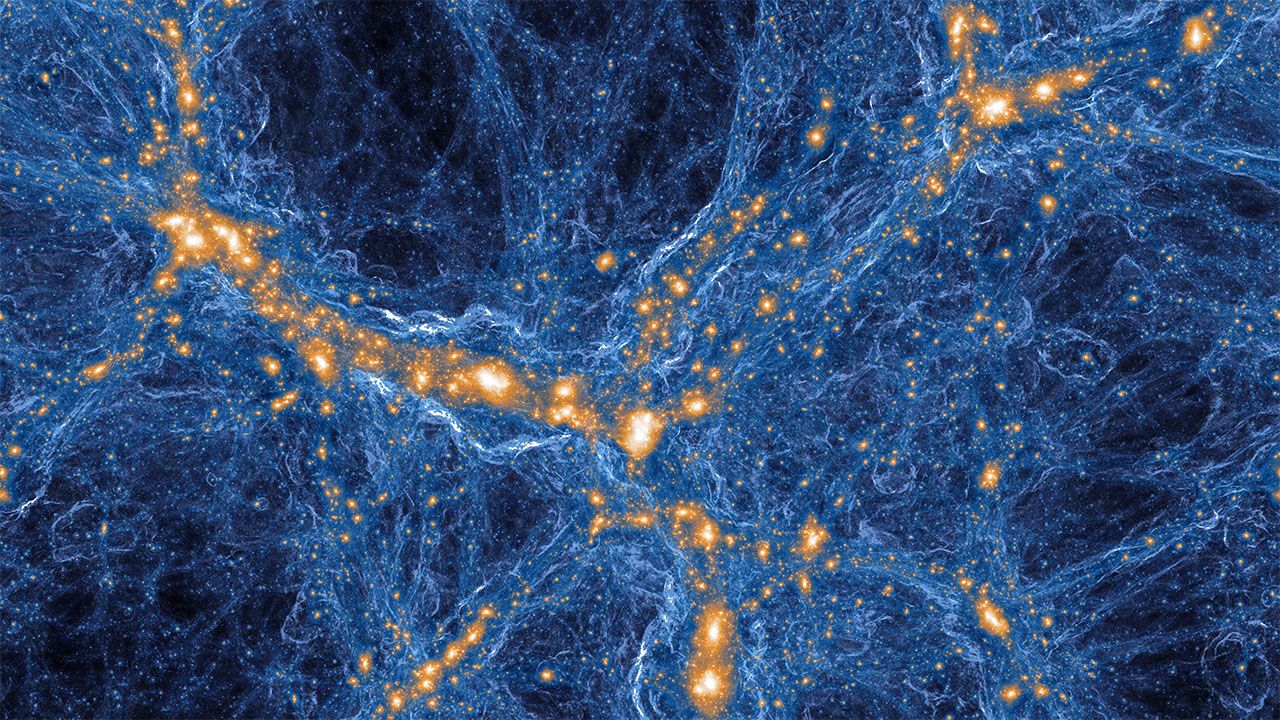

In general, modelers attack the problem by breaking it into billions of bits, either by dividing space into a 3D grid of subvolumes or by parceling the mass of dark and ordinary matter into swarms of particles. The simulation then tracks the interactions among those elements while ticking through cosmic time in, say, million-year steps. The computations strain even the most powerful supercomputers. BlueTides, for example, runs on Blue Waters—a supercomputer at the University of Illinois in Urbana that can perform 13 quadrillion calculations per second. Merely loading the model consumes 90% of the computer’s available memory, Feng says.

For years such simulations produced galaxies that were too gassy, massive, and blobby. But computer power has increased, and, more important, models of the radiation-matter feedback have improved. Now, hydrodynamic simulations have begun to produce the right number of galaxies of the right masses and shapes—spiral disks, squat ellipticals, spherical dwarfs, and oddball irregulars—says Volker Springel, a cosmologist at the Heidelberg Institute for Theoretical Studies in Germany who worked on Millennium and leads the Illustris simulation. “Until recently, the simulation field struggled to make spiral galaxies,” he says. “It’s only in the last 5 years that we’ve shown that you can make them.”

The models now show that, like people, galaxies tend to go through distinct life stages, Hopkins says. When young, a galaxy roils with activity, as one merger after another stretches and contorts it, inducing spurts of star formation. After a few billion years, the galaxy tends to settle into a relatively placid and stable middle age. Later, it can even slip into senescence as it loses its gas and the ability make stars—a transition our Milky Way appears to be making now, Hopkins says. But the wild and violent turns of adolescence make the particular path of any galaxy hard to predict, he says.

Read more