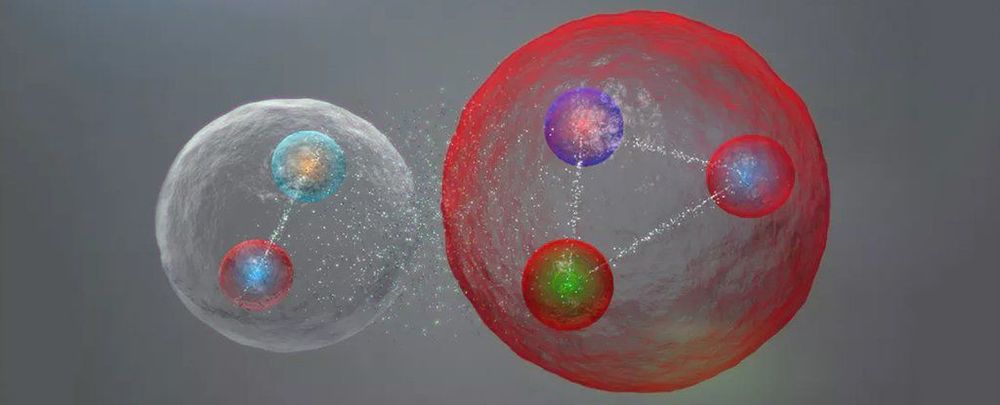

Why does the observable universe contain virtually no antimatter? Particles of antimatter have the same mass but opposite electrical charge of their matter counterparts. Very small amounts of antimatter can be created in the laboratory. However, hardly any antimatter is observed elsewhere in the universe.

Physicists believe that there were equal amounts of matter and antimatter in the early history of the universe – so how did the antimatter vanish? A Michigan State University researcher is part of a team of researchers that examines these questions in an article recently published in Reviews of Modern Physics.

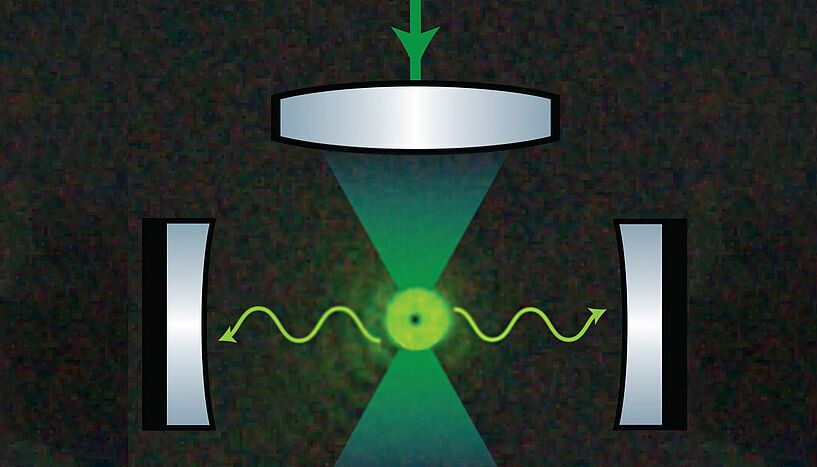

Jaideep Taggart Singh, MSU assistant professor of physics at the Facility for Rare Isotope Beams, or FRIB, studies atoms and molecules embedded in solids using lasers. Singh has a joint appointment in the MSU’s Department of Physics and Astronomy.