Scientists are searching for a ghostly neutrino particle that acts as its own antiparticle. If they find it, the discovery could resolve a cosmic conundrum: Why does matter exist at all?

Circa 2012

Imagine a clock that will keep perfect time forever or a device that opens new dimensions into quantum phenomena such as emergence and entanglement.

Imagine a clock that will keep perfect time forever, even after the heat-death of the universe. This is the “wow” factor behind a device known as a “space-time crystal,” a four-dimensional crystal that has periodic structure in time as well as space. However, there are also practical and important scientific reasons for constructing a space-time crystal. With such a 4D crystal, scientists would have a new and more effective means by which to study how complex physical properties and behaviors emerge from the collective interactions of large numbers of individual particles, the so-called many-body problem of physics. A space-time crystal could also be used to study phenomena in the quantum world, such as entanglement, in which an action on one particle impacts another particle even if the two particles are separated by vast distances.

A space-time crystal, however, has only existed as a concept in the minds of theoretical scientists with no serious idea as to how to actually build one – until now. An international team of scientists led by researchers with the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) has proposed the experimental design of a space-time crystal based on an electric-field ion trap and the Coulomb repulsion of particles that carry the same electrical charge.

Humans might not be so special after all.

#biophotonics #photonics

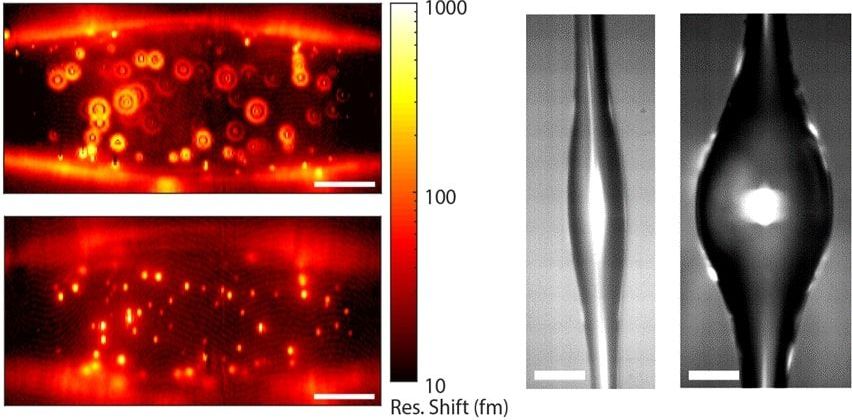

ONNA, Japan, Jan. 13, 2020 — Scientists at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST) Graduate University have developed a light-based device that can act as a biosensor, detecting biological substances in materials, such as harmful pathogens in food. The scientists said that their tool, an optical microresonator, is 280× more sensitive than current industry-standard biosensors, which can detect only cumulative effects of groups of particles, not individual molecules.

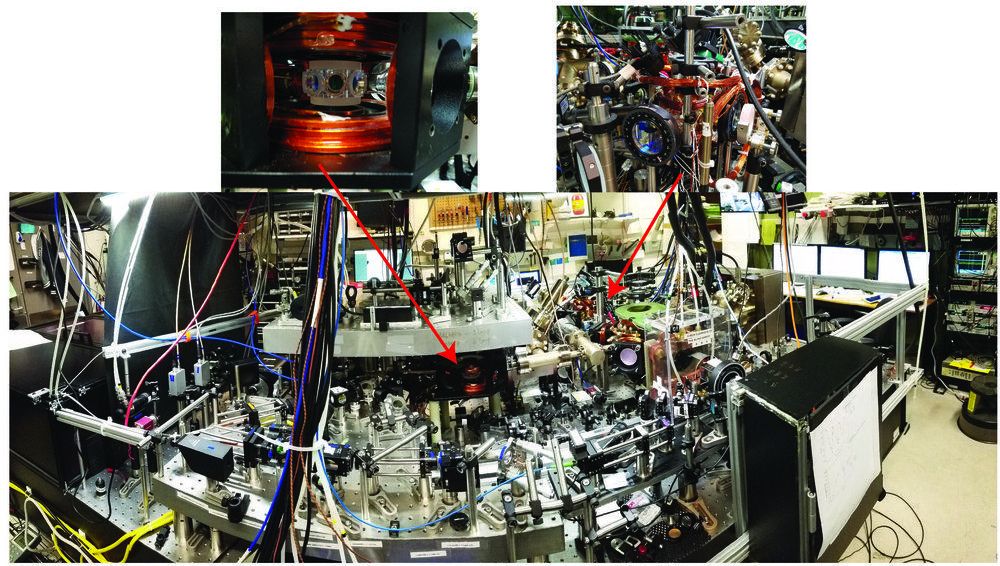

The concept of universal physics is intriguing, as it enables researchers to relate physical phenomena in a variety of systems, irrespective of their varying characteristics and complexities. Ultracold atomic systems are often perceived as ideal platforms for exploring universal physics, owing to the precise control of experimental parameters (such as the interaction strength, temperature, density, quantum states, dimensionality, and the trapping potential) that might be harder to tune in more conventional systems. In fact, ultracold atomic systems have been used to better understand a myriad of complex physical behavior, including those topics in cosmology, particle, nuclear, molecular physics, and most notably, in condensed matter physics, where the complexities of many-body quantum phenomena are more difficult to investigate using more traditional approaches.

Understanding the applicability and the robustness of universal physics is thus of great interest. Researchers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the University of Colorado Boulder have carried out a study, recently featured in Physical Review Letters, aimed at testing the limits to universality in an ultracold system.

“Unlike in other physical systems, the beauty of ultracold systems is that at times we are able to scrap the importance of the periodic table and demonstrate the similar phenomenon with any chosen atomic species (be it potassium, rubidium, lithium, strontium, etc.),” Roman Chapurin, one of the researchers who carried out the study, told Phys.org. “Universal behavior is independent of the microscopic details. Understanding the limitations of universal phenomenon is of great interest.”

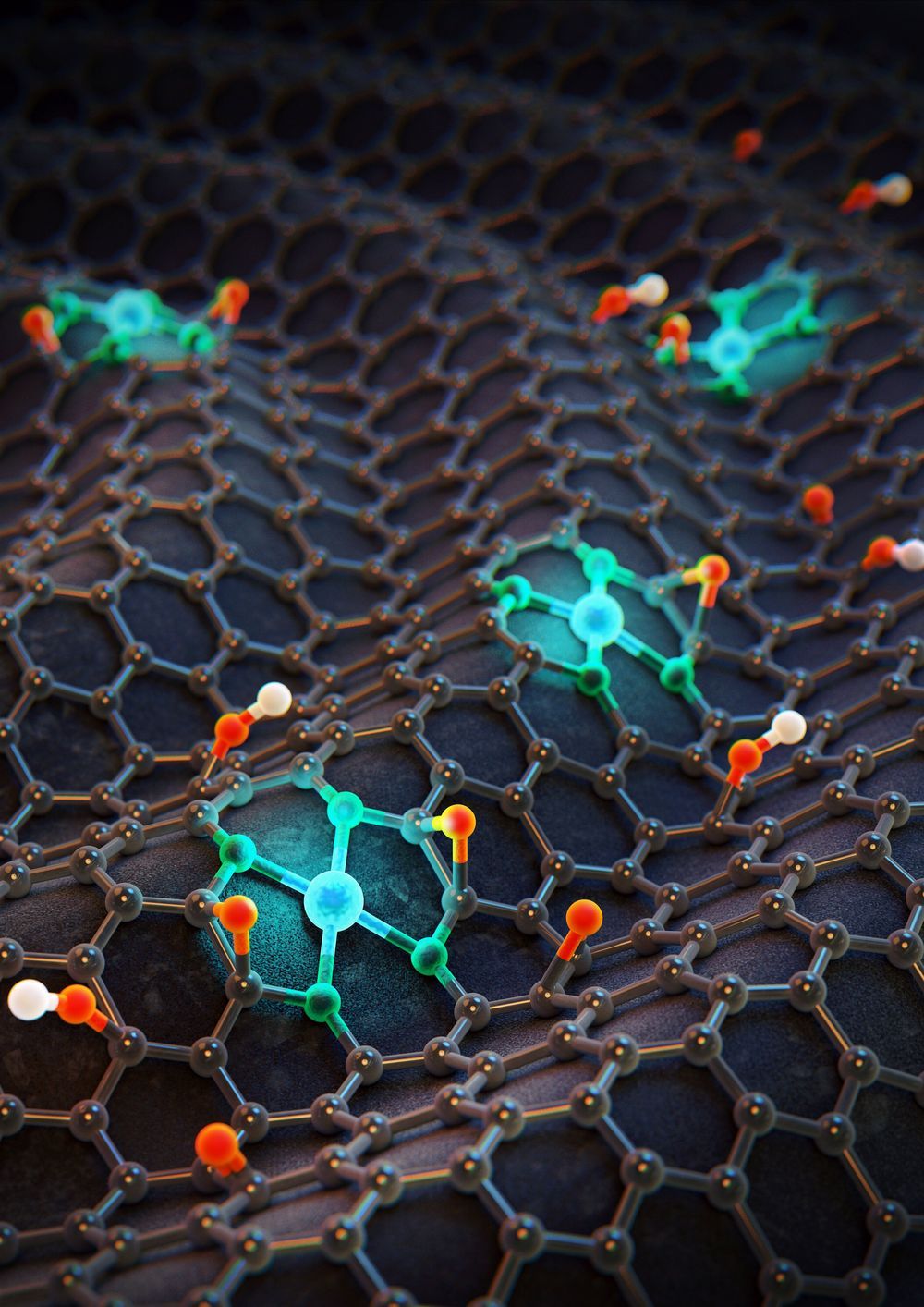

IBS scientists and their colleagues have recently report an ultimate electrocatalyst that addresses all of the issues that trouble H2O2 production. This new catalyst comprising the optimal Co-N4 molecules incorporated in nitrogen-doped graphene, Co1-NG(O), exhibits a record-high electrocatalytic reactivity, producing up to 8 times higher than the amount of H2O2 that can be generated from rather expensive noble metal-based electrocatalysts.

Just as we take a shower to wash away dirt and other particles, semiconductors also require a cleaning process. However, its cleaning goes to extremes to ensure even trace contaminants “leave no trace.” After all the chip fabrication materials are applied to a silicon wafer, a strict cleaning process is taken to remove residual particles. If this high-purity cleaning and particle-removal step goes wrong, electrical connections in the chip are likely to suffer from it. With ever-miniaturized gadgets on the market, the purity standards of the electronics industry reach a level equivalent to finding a needle in a desert.

That explains why hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), a major electronic cleaning chemical, is one of the most valuable chemical feedstocks that underpins the chip-making industry. Despite the ever-growing importance of H2O2, its industry has been left with an energy-intensive and multi-step method known as the anthraquinone process. This is an environmentally unfriendly process which involves the hydrogenation step using expensive palladium catalysts. Alternatively, H2O2 can be synthesized directly from H2 and O2 gas, although the reactivity is still very poor and it requires high pressure. Another eco-friendly method is to electrochemically reduce oxygen to H2O2 a via 2-electron pathway. Recently, noble metal-based electrocatalysts (for example, Au-Pd, Pt-Hg, and Pd-Hg) have been demonstrated to show H2O2 productivity although such expensive investments have seen low returns that fail to meet the scalable industry needs.

Stars have life cycles. They’re born when bits of dust and gas floating through space find each other and collapse in on each other and heat up. They burn for millions to billions of years, and then they die. When they die, they pitch the particles that formed in their winds out into space, and those bits of stardust eventually form new stars, along with new planets and moons and meteorites. And in a meteorite that fell fifty years ago in Australia, scientists have now discovered stardust that formed 5 to 7 billion years ago-the oldest solid material ever found on Earth.

“This is one of the most exciting studies I’ve worked on,” says Philipp Heck, a curator at the Field Museum, associate professor at the University of Chicago, and lead author of a paper describing the findings in PNAS. “These are the oldest solid materials ever found, and they tell us about how stars formed in our galaxy.”

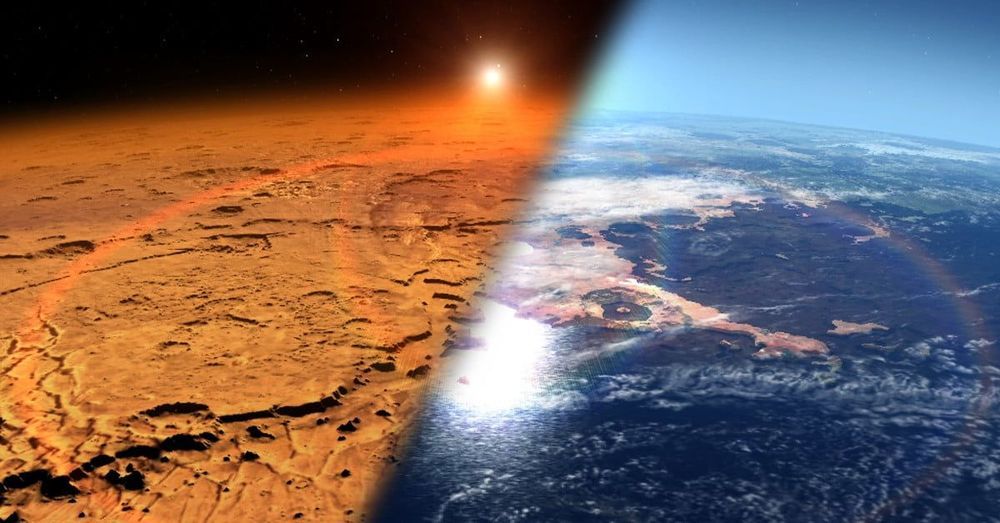

Billions of years ago, Mars could have been a planet very like Earth with copious liquid water on its surface. But over time, that water rose into Mars’s thin atmosphere and evaporated off into space. There are only very small amounts of water vapor left in the atmosphere today, and a new study shows that vapor is being lost even faster than previously believed.

The research, published in the journal Science, used data from the Trace Gas Orbiter in orbit around Mars to see how water moved up and down through the layers of the Martian atmosphere in order to understand how fast it evaporates away. They found that the vapor changes through the seasons and that in the warmer months the atmosphere hosts a whole lot more water than expected, in a state called “supersaturation.”

When the atmosphere becomes supersaturated, this makes the evaporation of water happen even faster. “Unconstrained by saturation, the water vapor globally penetrates through the cloud level, regardless of the dust distribution, facilitating the loss of water to space,” the authors explain. Even when the density of dust or ice particles in the atmosphere changes, that still doesn’t stop supersaturation, so the evaporation of water continues at a brisk pace.