A new study by Florida State University researchers may help answer some of the most perplexing questions surrounding Alzheimer’s disease, an incurable and progressive illness affecting millions of families around the globe.

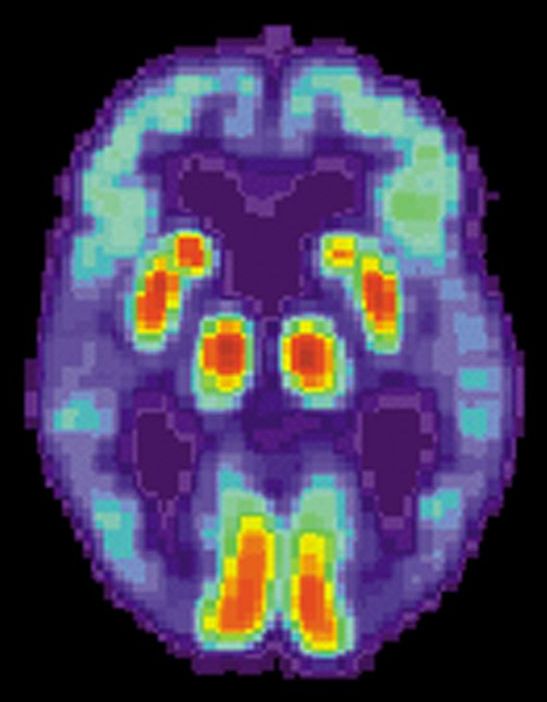

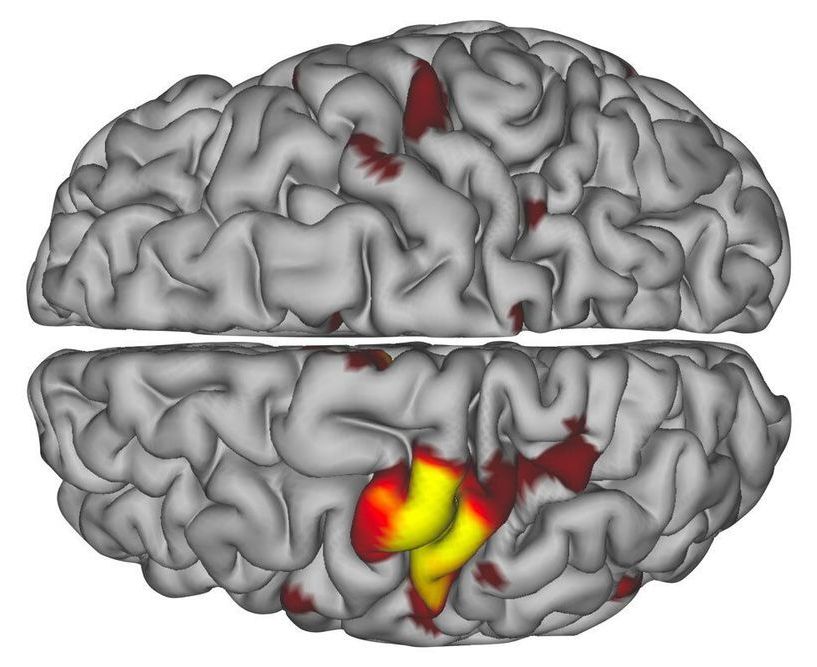

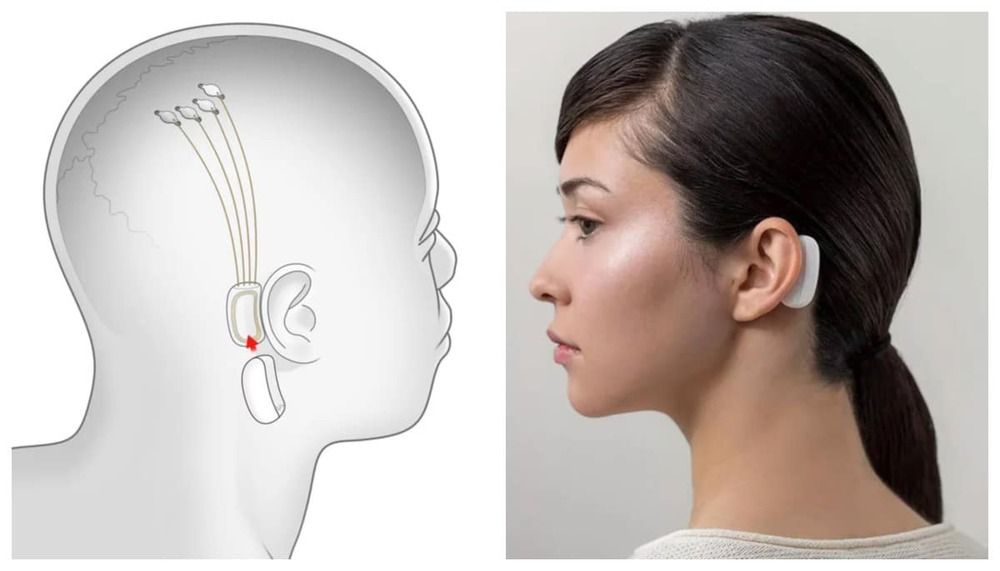

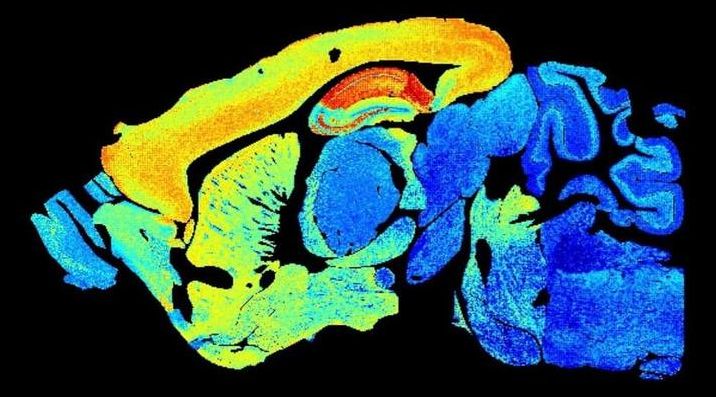

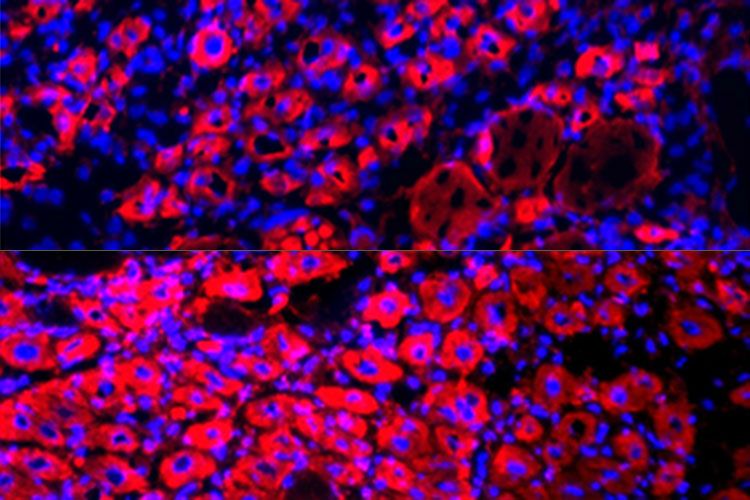

FSU Assistant Professor of Psychology Aaron Wilber and graduate student Sarah Danielle Benthem showed that the way two parts of the brain interact during sleep may explain symptoms experienced by Alzheimer’s patients, a finding that opens up new doors in dementia research. It is believed that these interactions during sleep allow memories to form and thus failure of this normal system in a brain of a person with Alzheimer’s disease may explain why memory is impaired.

The study, a collaboration among the FSU Program in Neuroscience, the University of California, Irvine, and the University of Lethbridge in Alberta, Canada, was published online in the journal Current Biology and will appear in the publication’s July 6 issue.