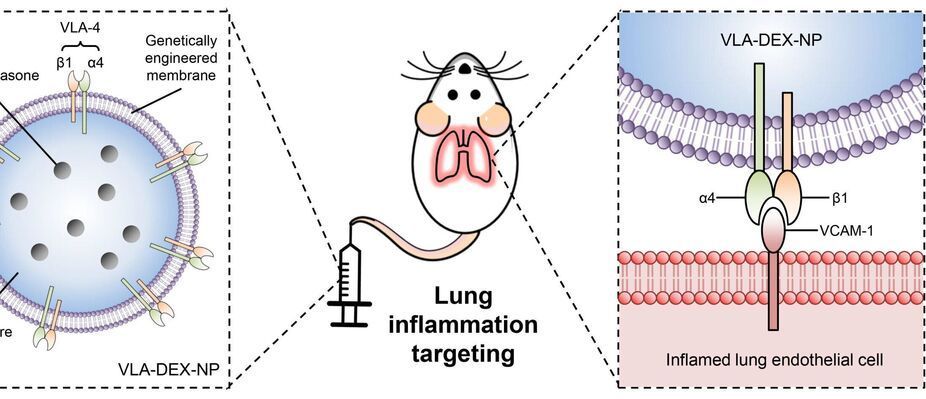

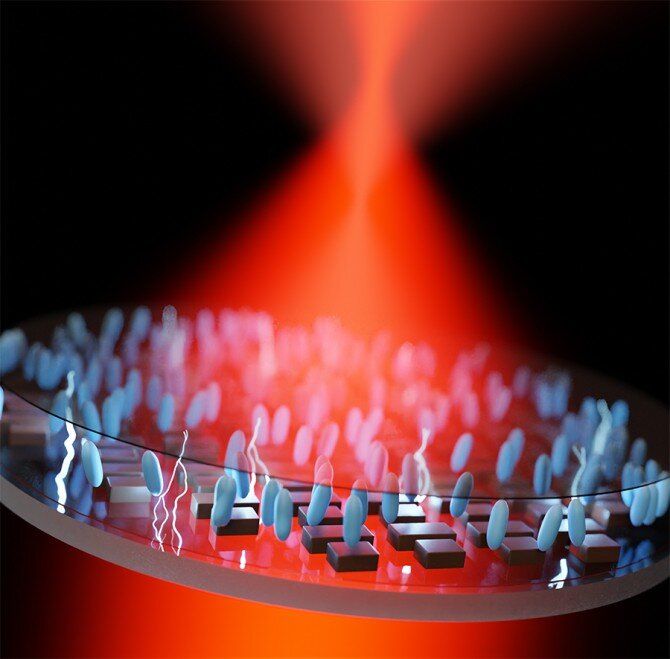

Nanoengineers at the University of California San Diego have developed immune cell-mimicking nanoparticles that target inflammation in the lungs and deliver drugs directly where they’re needed. As a proof of concept, the researchers filled the nanoparticles with the drug dexamethasone and administered them to mice with inflamed lung tissue. Inflammation was completely treated in mice given the nanoparticles, at a drug concentration where standard delivery methods did not have any efficacy.

The researchers reported their findings in Science Advances on June 16.

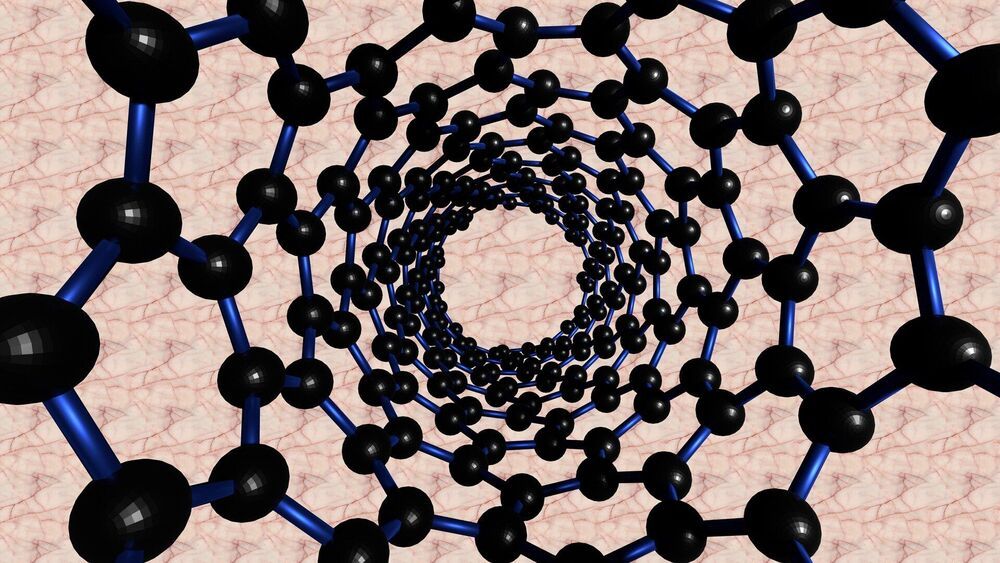

What’s special about these nanoparticles is that they are coated in a cell membrane that’s been genetically engineered to look for and bind to inflamed lung cells. They are the latest in the line of so-called cell membrane-coated nanoparticles that have been developed by the lab of UC San Diego nanoengineering professor Liangfang Zhang. His lab has previously used cell membrane-coated nanoparticles to absorb toxins produced by MRSA; treat sepsis; and train the immune system to fight cancer. But while these previous cell membranes were naturally derived from the body’s cells, the cell membranes used to coat this dexamethasone-filled nanoparticle were not.