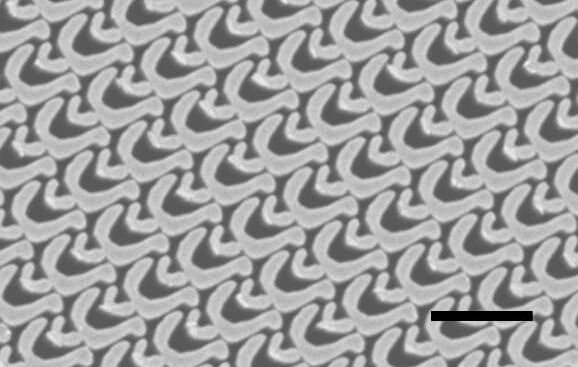

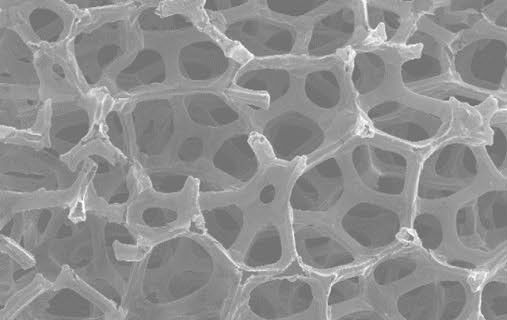

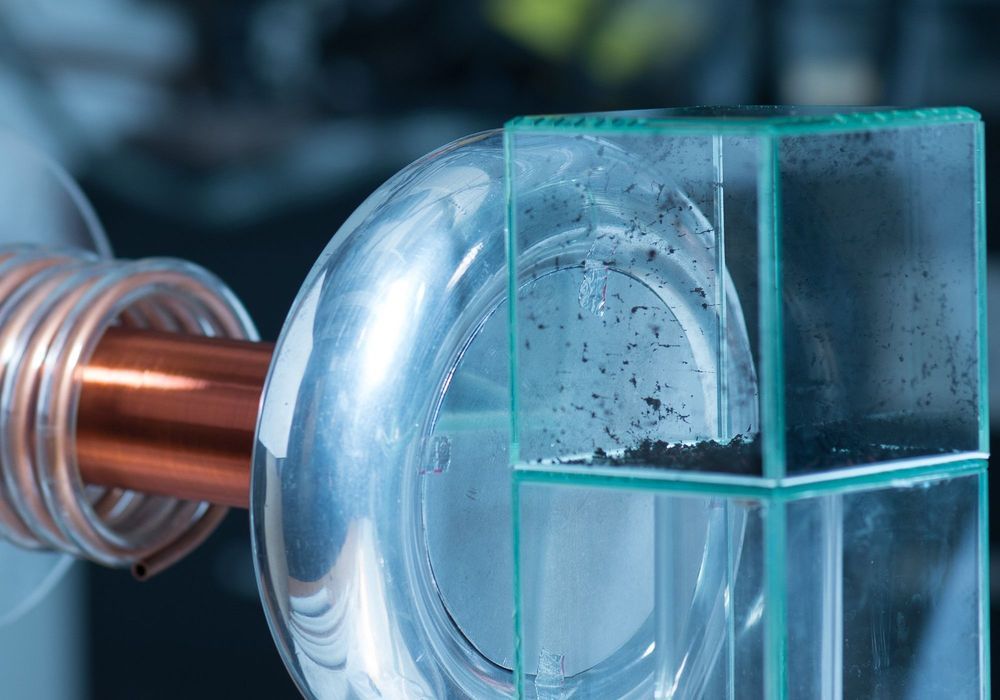

In the periodic table of elements there is one golden rule for carbon, oxygen and other light elements: Under high pressures, they have similar structures to heavier elements in the same group of elements. But nitrogen always seemed unwilling to toe the line. However, high-pressure chemistry researchers of the University of Bayreuth have disproved this special status. Out of nitrogen, they created a crystalline structure which, under normal conditions, occurs in black phosphorus and arsenic. The structure contains two-dimensional atomic layers, and is therefore of great interest for high-tech electronics. The scientists have presented this “black nitrogen” in Physical Review Letters.

Nitrogen—an exception in the periodic system?

When you arrange the chemical elements in ascending order according to their number of protons and look at their properties, it soon becomes obvious that certain properties recur at large intervals (periods). The periodic table of elements brings these repetitions into focus. Elements with similar properties are placed one below the other in the same column, and thus form a group of elements. At the top of a column is the element that has the fewest protons and the lowest weight compared to the other group members. Nitrogen heads element group 15, but was previously considered the “black sheep” of the group. The reason: In earlier high-pressure experiments, nitrogen showed no structures similar to those exhibited under normal conditions by the heavier elements of this group—specifically, phosphorus, arsenic and antimony. Instead, such similarities are observed at high pressures in the neighboring groups headed by carbon and oxygen.