Transhumanism appearing in the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s (AAAS) magazine: Science…

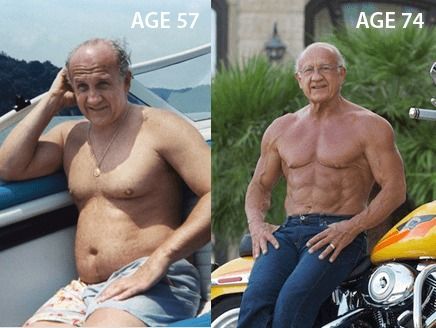

Modern technology and modern medical practice have evolved over the past decades, enabling us to enhance and extend human life to an unprecedented degree. The two books under review examine this phenomenon from remarkably different perspectives.

Mark O’Connell’s To Be a Machine is an examination of transhumanism, a movement characterized by technologies that seek to transform the human condition and extend life spans indefinitely. O’Connell, a journalist, makes his own prejudices clear: “I am not now, nor have I ever been, a transhumanist,” he writes. However, this does not stop him from thoughtfully surveying the movement.

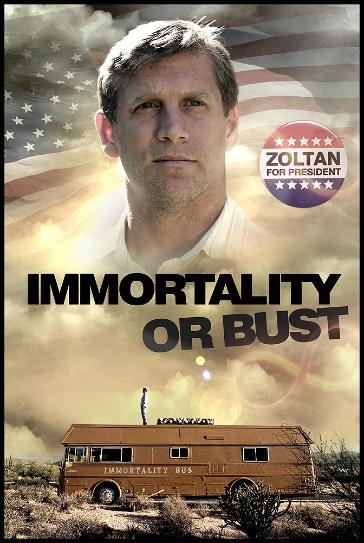

The book mostly comprises O’Connell’s encounters with transhumanist thought leaders in an assortment of locales ranging from lecture halls to Silicon Valley start-ups to transhumanist conferences and even the campaign trail, where O’Connell interviews Zoltan Istvan, a transhumanist and 2016 U.S. presidential candidate whose goal is “to promote investment in longevity science.”

O’Connell’s interaction with Max More, the president and CEO of the Alcor Life Extension Foundation, the world’s largest commercial cryopreservation facility, is particularly timely, because the legal, social, and ethical issues related to cryopreservation are far from settled. Likewise, as O’Connell notes, the promise of cryonics relies on the improbable notion that science will someday enable reanimation.

Read more