Much like US corporations do now.

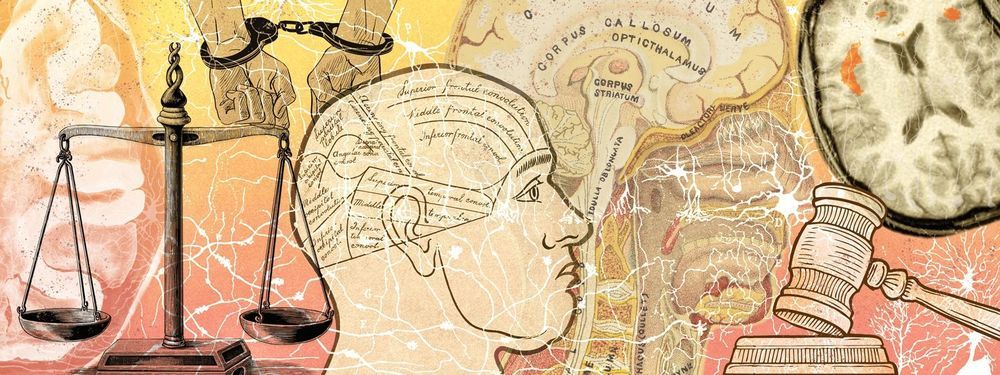

Debates about rights are frequently framed around the concept of legal personhood. Personhood is granted not just to human beings but also to some non-human entities, such as corporations or governments. Legal entities, aka legal persons, are granted certain privileges and responsibilities by the jurisdictions in which they are recognized, and many such rights are not available to non-person agents. Attempting to secure legal personhood is often seen as a potential pathway to get certain rights and protections for animals1, fetuses2, trees and rivers 3, and artificially intelligent (AI) agents4.

It is commonly believed that a new law or judicial ruling is necessary to grant personhood to a new type of entity. But recent legal literature 5–8 suggests that loopholes in the current law may permit legal personhood to be granted to AI/software without the need to change the law or persuade a court.

For example, L. M. LoPucki6 points out, citing Shawn Bayern’s work on conferring legal personhood on AI7, 8, “Professor Shawn Bayern demonstrated that anyone can confer legal personhood on an autonomous computer algorithm merely by putting it in control of a limited liability company (LLC). The algorithm can exercise the rights of the entity, making them effectively rights of the algorithm. The rights of such an algorithmic entity (AE) would include the rights to privacy, to own property, to enter into contracts, to be represented by counsel, to be free from unreasonable search and seizure, to equal protection of the laws, to speak freely, and perhaps even to spend money on political campaigns. Once an algorithm had such rights, Bayern observed, it would also have the power to confer equivalent rights on other algorithms by forming additional entities and putting those algorithms in control of them.”6. (See Note 1.)