Kin Insurance has raised $47 million in fresh funding to help launch its Kin Interinsurance Network, which will provide home insurance to residents in Florida. August Capital reportedly led the…

The year 2017 saw the second highest global tree cover loss recorded in the history of this planet, according to the World Economic Forum. Researchers at the University of Maryland (USA) found an area of tree loss equal to the size of Bangladesh. That equates to losing 40 soccer fields covered in trees every minute for a year. But guess what, Costa Rica took the fight in the other direction, declaring they had officially doubled their tropical rainforests since 2001. Doubled!

How can the world learn from Costa Rica’s experience and use it as a model for other nations? It helps to take a closer look at exactly what Costa Rica has done right in managing this issue, while other countries have failed miserably. In the mid-20th century, three quarters of Costa Rica was covered in lush, verdant tree canopy. Then came loggers, who savagely cleared acres and acres of pristine rainforest, lining their pockets by selling off Costa Rica’s natural resources. At the same time, of course, they were destroying the natural habitats of Costa Rica’s indigenous creatures, for instance Golden toads and Poison dart frogs.

But then, something changed radically in the thought processes of Costa Rican policy makers, and the rate of deforestation slowed, until it eventually dropped to zero. What happened? Costa Rica awakened to the potential of its rich ecosystems and began vigorously safeguarding them. Healthy ecosystems meant tourist dollars and employment opportunities for Ticos throughout the country.

His work is one of a series of projects that have been set up by Doing It Together Science (Ditos), an EU citizen science programme that has been co-ordinated by researchers at University College London. Two major strands were selected for special attention: bio-design – the use of living things (such as bacteria and plants) in product design, and environmental monitoring. As one of the latter projects, a group at Durham University, led by Dr Phil Stephens and including researcher Pen-Yuan Hsing, set up MammalWeb which uses camera traps – digital cameras triggered by an animal’s heat and movement – to monitor wildlife in the north-east. Ascroft was one of their first volunteers.

Roland Ascroft’s first attempt to become a citizen scientist was nearly his last. The 63-year-old conservationist volunteered to take part in a wildlife monitoring project in 2015 and began by placing a camera trap in the woods opposite his house at New Brancepeth, near Durham. For three weeks he checked every day to see if the device had been triggered by animals moving in front of it, but found nothing had set it off.

“I was about to give up when I moved my camera trap for one last attempt – and found next morning that I had photographed a roe deer in the early morning,” says Ascroft. “I was hooked.”

Since then Ascroft has set up 20 camera traps that have taken more than 75,000 remotely triggered photographs of wildlife in Deerness Woods.

O.o.

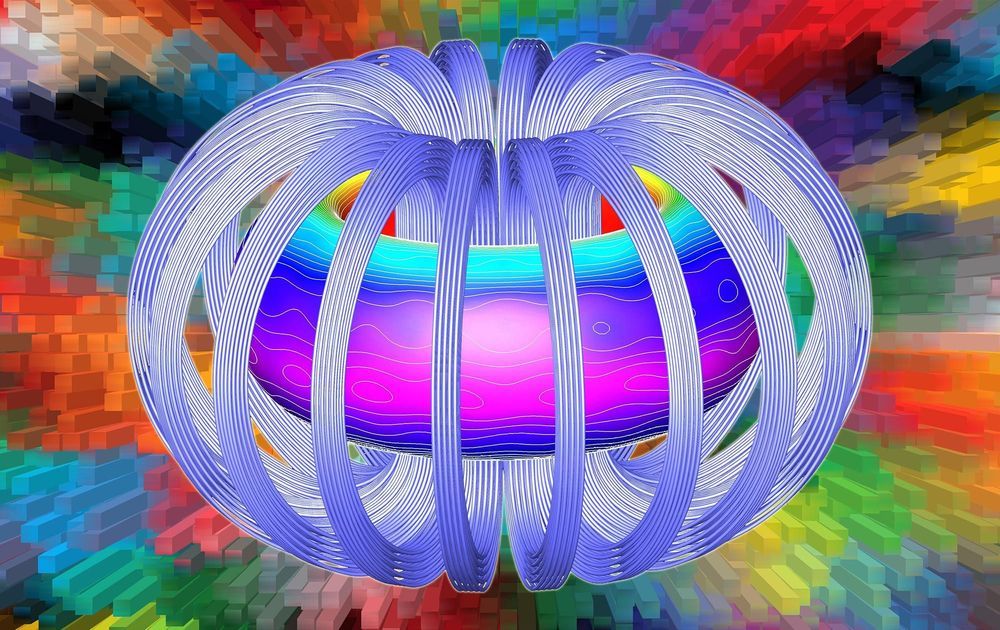

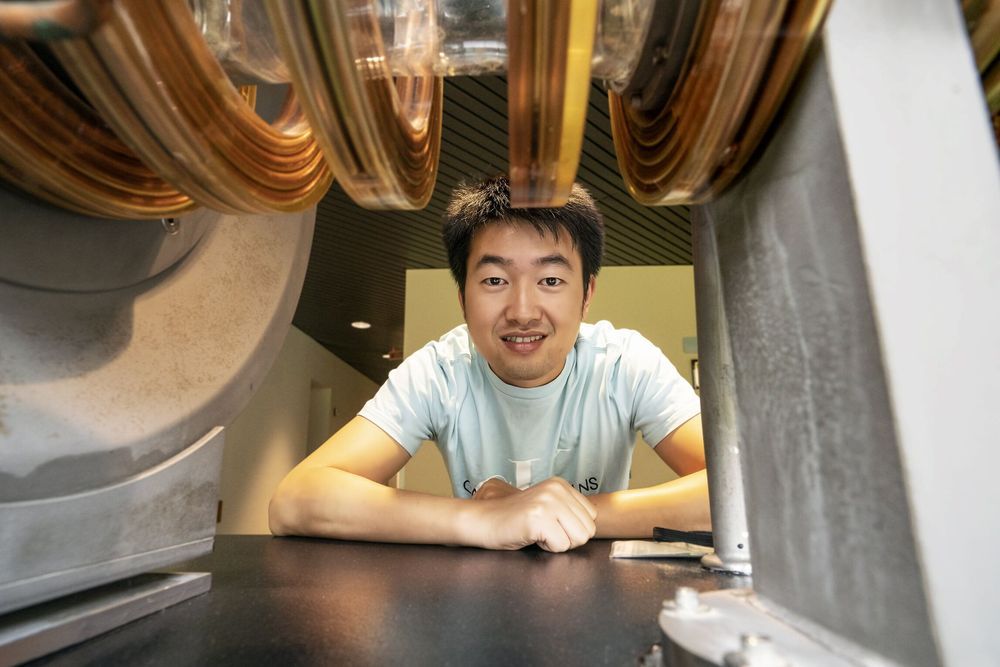

Stellarators, twisty machines that house fusion reactions, rely on complex magnetic coils that are challenging to design and build. Now, a physicist at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory ( PPPL ) has developed a mathematical technique to help simplify the design of the coils, making stellarators a potentially more cost-effective facility for producing fusion energy.

“Our main result is that we came up with a new method of identifying the irregular magnetic fields produced by stellarator coils,” said physicist Caoxiang Zhu, lead author of a paper reporting the results in Nuclear Fusion. “This technique can let you know in advance which coil shapes and placements could harm the plasma ’s magnetic confinement, promising a shorter construction time and reduced costs.”

Fusion, the power that drives the sun and stars, is the fusing of light elements in the form of plasma — the hot, charged state of matter composed of free electrons and atomic nuclei — that generates massive amounts of energy. Twisty, cruller-shaped stellarators are an alternative to doughnut-shaped tokamaks that are more commonly used by scientists seeking to replicate fusion on Earth for a virtually inexhaustible supply of power to generate electricity.

If you’re looking to build a new home on coastal waters where hurricanes are known to roam, you might want to skip the two-by-fours and cement and instead start drinking bottled soda. A Canadian company has recently completed construction of a home with exterior walls made from recycled plastic, and it’s claimed to be able to withstand winds gusting at over 300 miles per hour.

Built by JD Composites, the three bedroom home is situated near the Meteghan River in Nova Scotia. Aside from a distinct lack of trees, gardens, and neighbors, the house looks like any other dwelling with a clean modern design and a minimalist facade. Inside it’s fully furnished and finished with drywall covered lumber walls, but the exterior is what makes the house appealing as a new, and seemingly much improved, approach to construction.

“We don’t have the official results of that testing, but we are told it went very, very well, so we are really excited about that,” Lindsey said.

Key to SNC’s habitat design is its ability to grow in volume once it is launched into space. The Large Inflatable Fabric Environment, or LIFE, habitat can start out compact enough to fit inside an 18-foot (5.4 meters) rocket fairing but then expand to 27 feet in diameter and 27 feet long (8 by 8 m).

Stellarators, twisty machines that house fusion reactions, rely on complex magnetic coils that are challenging to design and build. Now, a physicist at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) has developed a mathematical technique to help simplify the design of the coils, making stellarators a potentially more cost-effective facility for producing fusion energy.

“Our main result is that we came up with a new method of identifying the irregular magnetic fields produced by stellarator coils,” said physicist Caoxiang Zhu, lead author of a paper reporting the results in Nuclear Fusion. “This technique can let you know in advance which coil shapes and placements could harm the plasma’s magnetic confinement, promising a shorter construction time and reduced costs.”

Fusion, the power that drives the sun and stars, is the fusing of light elements in the form of plasma—the hot, charged state of matter composed of free electrons and atomic nuclei—that generates massive amounts of energy. Twisty, cruller-shaped stellarators are an alternative to doughnut-shaped tokamaks that are more commonly used by scientists seeking to replicate fusion on Earth for a virtually inexhaustible supply of power to generate electricity.

By his late 20s, Moe had attained the young adult dream. A technology job paid for his studio apartment just blocks from the beach in Santa Barbara, California. Leisure time was crowded with close friends and hobbies, such as playing the guitar. He had even earned his pilot’s license. “There was nothing I could have complained about,” he says.

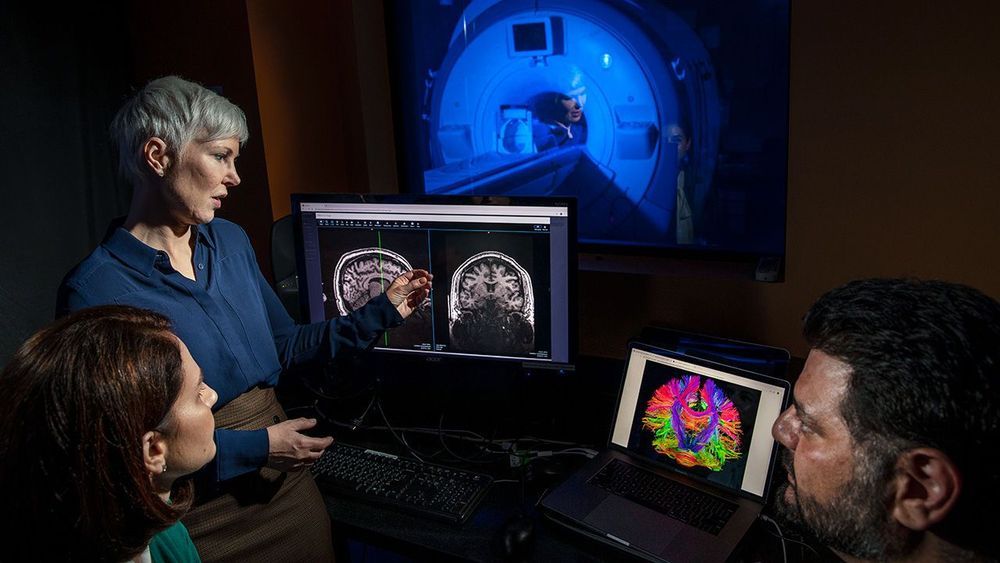

Yet Moe soon began a slide he couldn’t control. Insomnia struck, along with panic attacks. As the mild depression he’d experienced since childhood deepened, Moe’s life collapsed. He lost his job, abandoned his interests, and withdrew from his friends. “I lost the emotions that made me feel human,” Moe says. (He asked that this story not use his full name.)

Although many people with depression respond well to treatment, Moe wasn’t one of them. Now 37, he has tried antidepressant drugs and cycled through years of therapy. Moe has never attempted suicide, but he falls into a high-risk group: Though most people with depression don’t die by suicide, about 30% of those who don’t respond to multiple antidepressant drugs or therapy make at least one attempt. Moe was desperate for relief and fearful for his future. So when he heard about a clinical trial testing a new approach to treating depression at Stanford University in Palo Alto, California, near his home, he signed up.

Endemic to the mountain forests of New Guinea, the King of Saxony bird-of-paradise (Pteridophora alberti) is best-known for the flamboyant, mate-attracting efforts of its males. The bird’s courtship displays – which often double as a means of keeping competitors at a comfortable distance – make use of bright yellow breast feathers, wildly waving head plumes and peppy dance manoeuvres capped off with an exceptionally outsized, almost otherworldly bit of squawking. This video from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology provides a rare glimpse into the world of this idiosyncratic little bird, which has proven notoriously difficult to photograph in its rugged natural habitat.

Director: Tim Laman

Websites: Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Birds of Paradise Project.

The art of matchmaking has traditionally been the province of grandmas and best friends, parents, and even—sometimes—complete strangers. Recently they’ve been replaced by swipes and algorithms in an effort to automate the search for love. But Kevin Teman wants to take things one step further.

The Denver-based founder of a startup called AIMM has built an app that matches prospective partners using just what they say to a British-accented AI. Users talk to the female-sounding software to complete a profile: pick out your dream home, declare whether you consider yourself a “cat person,” and describe how you would surprise a potential partner.

At first glance, that doesn’t seem too different from the usual swiping-texting-dating formula of modern online romance. But AIMM, whose name is an acronym for “artificially intelligent matchmaker,” comes with a twist: the AI coaches users through a first phone call, gives advice for the first date, and even provides feedback afterwards. Call it Cyrano de Bergerac for the smartphone era.