Mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with many mitochondrial diseases, most of which are the result of dysfunctional mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). Mitochondrial OXPHOS accounts for the generation of most of the cellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) in a cell. The OXPHOS function largely depends on the coordinated expression of the proteins encoded by both nuclear and mitochondrial genomes. The human mitochondrial genome encodes for 13 polypeptides of the OXPHOS, and the nuclear genome encodes the remaining more than 85 polypeptides required for the assembly of OXPHOS system. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) depletion impairs OXPHOS that leads to mtDNA depletion syndromes (MDSs)1, 2. The MDSs are a heterogeneous group of disorders, characterized by low mtDNA levels in specific tissues. In different target organs, mtDNA depletion leads to specific pathological changes. MDS results from the genetic defects in the nuclear-encoded genes that participate in mtDNA replication, and mitochondrial nucleotide metabolism and nucleotide salvage pathway1, 4,5,6,7,8,9,10. mtDNA depletion is also implicated in other human diseases such as mitochondrial diseases, cardiovascular11, 12, diabetes13,14,15, age-associated neurological disorders16,17,18, and cancer19,20,21,22,23,24,25.

A general decline in mitochondrial function has been extensively reported during aging26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33. Furthermore, mitochondrial dysfunction is known to be a driving force underlying age-related human diseases16,17,18, 34,35,36. A mouse that carries elevated mtDNA mutation is also shown to present signs of premature aging37, 38. In addition to mutations in mtDNA, studies also suggest a decrease in mtDNA content and mitochondrial number with age27, 29, 32, 33, 39. Notably, there is an age-related mtDNA depletion in a number of tissues40,41,42. mtDNA depletion is also frequently observed among women with premature ovarian aging43. Low mtDNA copy number is linked to frailty and, for a multiethnic population, is a predictor of all-cause mortality44. A recent study revealed that humans on an average lose about four copies of mtDNA every ten years. This study also identified an association of decrease in mtDNA copy number with age-related physiological parameters39.

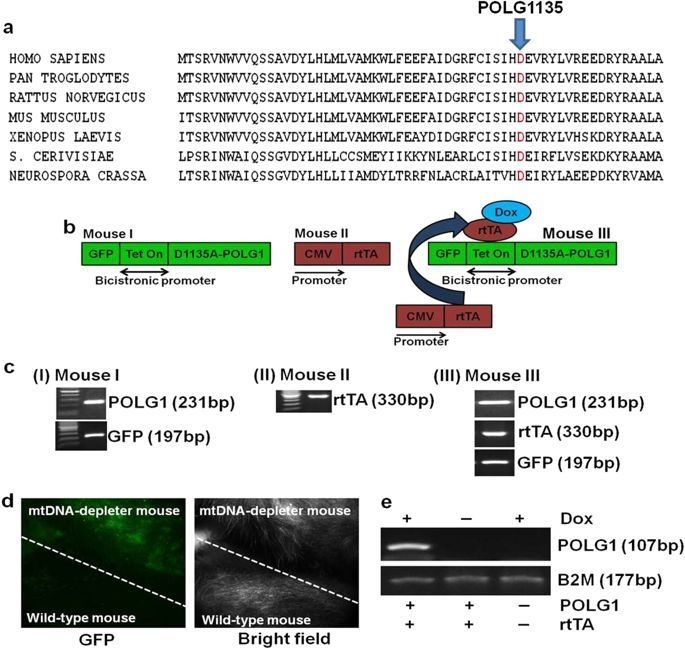

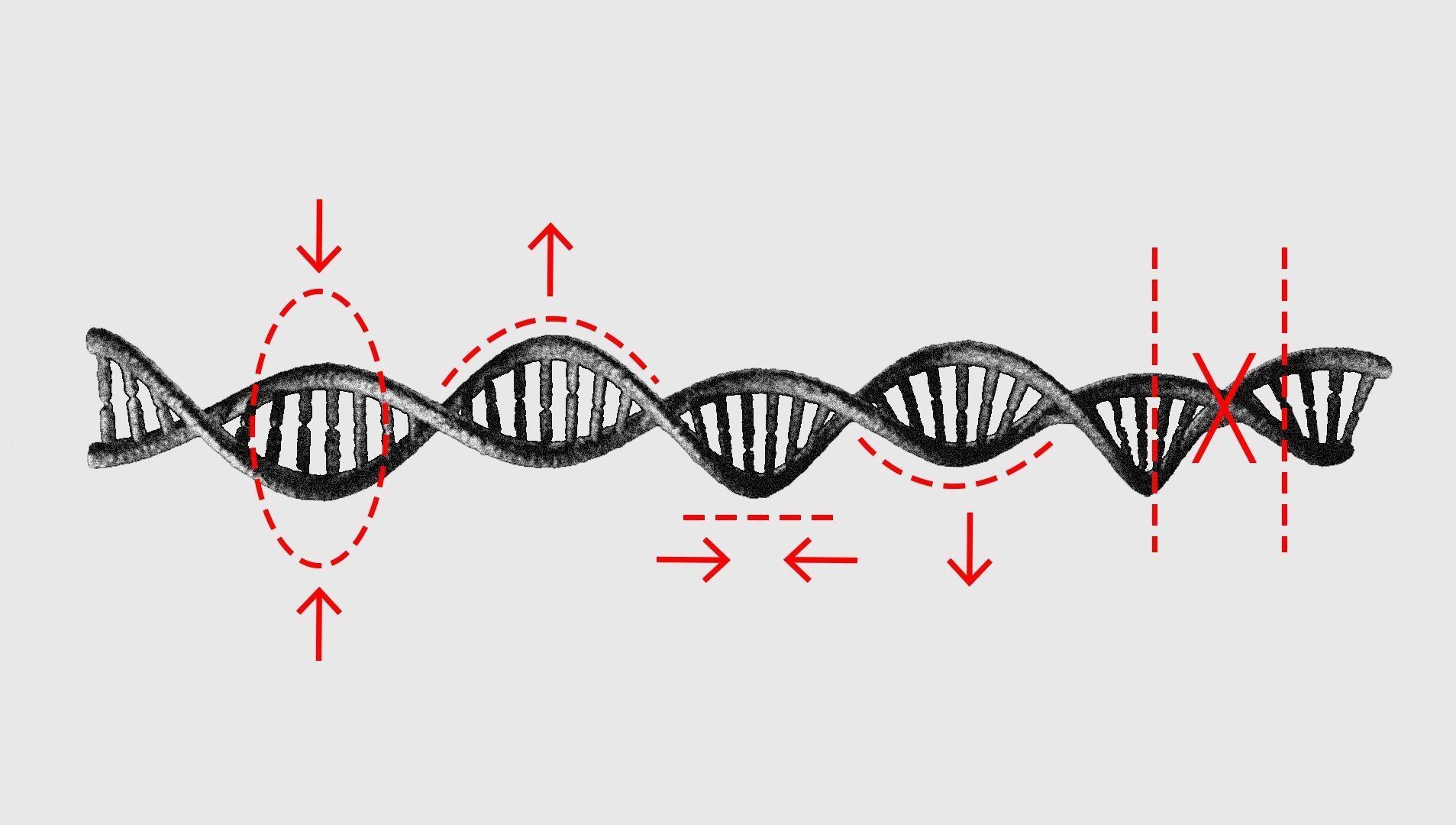

To help define the role of mtDNA depletion in aging and various diseases, we created an inducible mouse expressing, in the polymerase domain of POLG1, a dominant-negative (DN) mutation that induces depletion of mtDNA in the whole animal. Interestingly, skin wrinkles and visual hair loss were among the earliest and most predominant phenotypic changes observed in these mice. In the present study, we demonstrate that mtDNA depletion-induced phenotypic changes can be reversed by restoration of mitochondrial function upon repletion of mtDNA.

Read more