Sorry, T-Rex — blame Nemesis.

Most if not all stars in the universe might also have a twin.

While cholera rages across many regions of the world, a team of microbiologists and plant scientists has pinpointed a genetic weakness in the pandemic’s armor, which could lead to future treatments.

The current cholera pandemic began in Indonesia in 1961. Rather than fade away like its six previous worldwide outbreak predecessors, the responsible strain is thriving and actually picking up steam. A discovery, led by scientists from Michigan State University and Tufts University and featured in the current issue of PNAS, shows the key genetic change the seventh pandemic acquired to thrive for more than 50 years.

The interdisciplinary team of scientists reveal the first ever signaling network for a new bacterial signal, cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP), in the human cholera pathogen. The team also identified the first protein receptor of cGAMP as a phospholipase enzyme that remodels the V. cholerae membrane when cGAMP is produced.

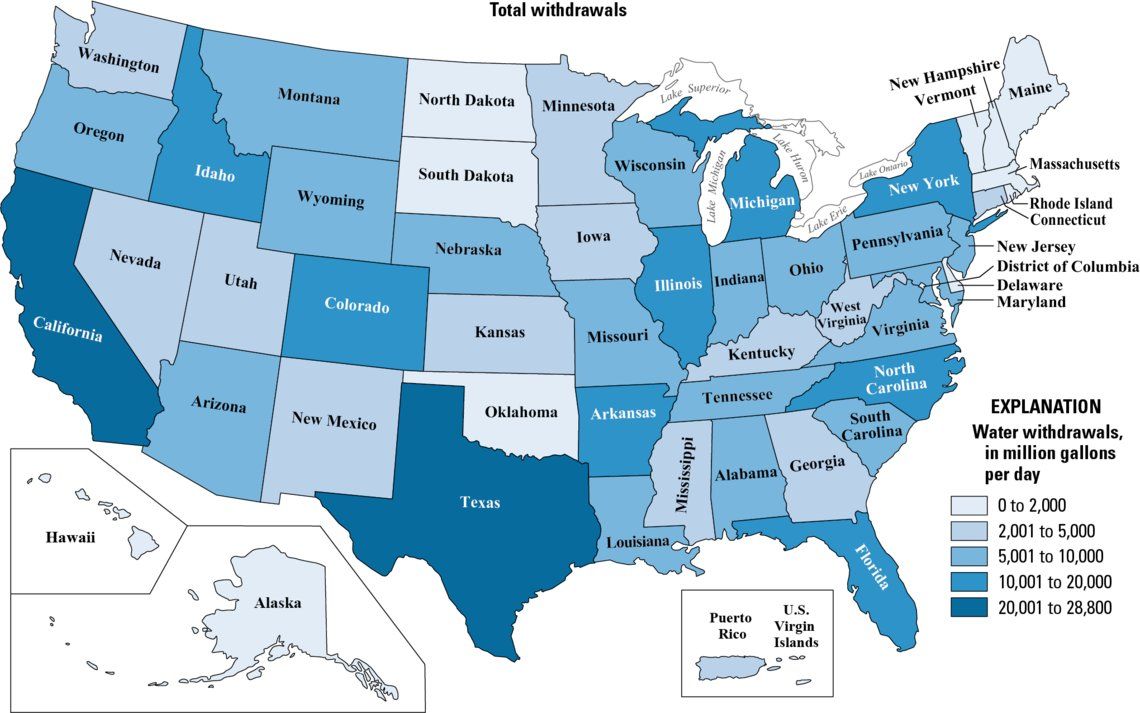

Reductions in water use first observed in 2010 continue, show ongoing effort towards “efficient use of critical water resources.”

Water use across the country reached its lowest recorded level in 45 years. According to a new USGS report, 322 billion gallons of water per day (Bgal/d) were withdrawn for use in the United States during 2015.

This represents a 9 percent reduction of water use from 2010 when about 354 Bgal/d were withdrawn and the lowest level since before 1970 (370 Bgal/d).