In a study published in Environment International researchers at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden show how PFAS industrial chemicals, which are used in many consumer products, pass through the placenta throughout pregnancy to accumulate in fetal tissue. Further research is now needed to ascertain the effect that highly persistent PFAS chemicals have on the fetus.

The PFAS (perfluoroalkyl substances) group comprises thousands of human-made chemicals, which, thanks to their water- and grease-resistant properties, are used in everything from frying pans and food packaging to clothes, cleaning agents and firefighting foams.

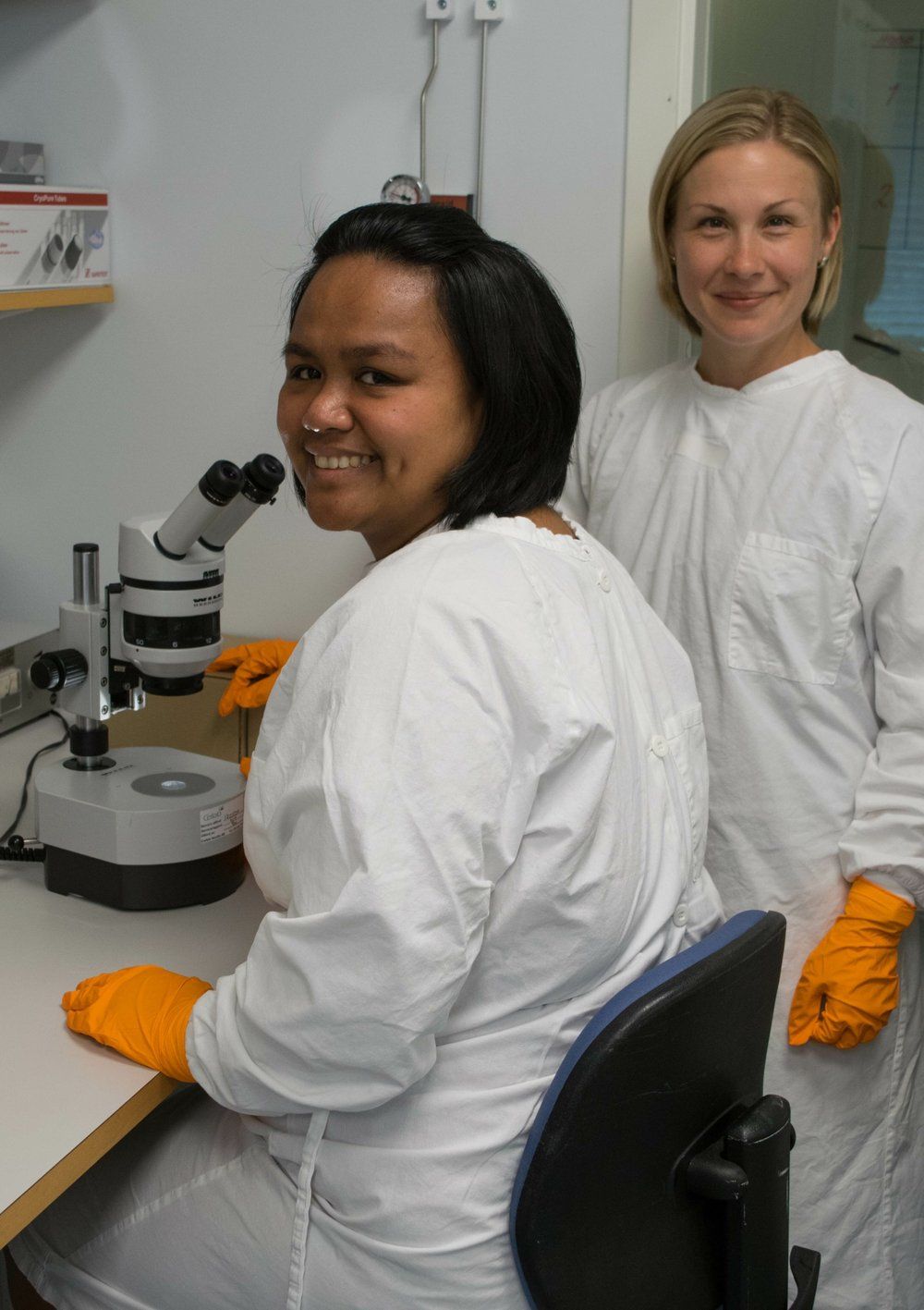

“We’ve focused on six of these PFAS substances and found that all appear to the same extent in fetal tissue as in the placenta,” says Richelle Duque Björvang, doctoral student at the Department of Clinical Science, Intervention and Technology, Karolinska Institutet. “So when the baby is born, it already has a build-up of these chemicals in the lungs, liver, brain, and elsewhere in the body.”