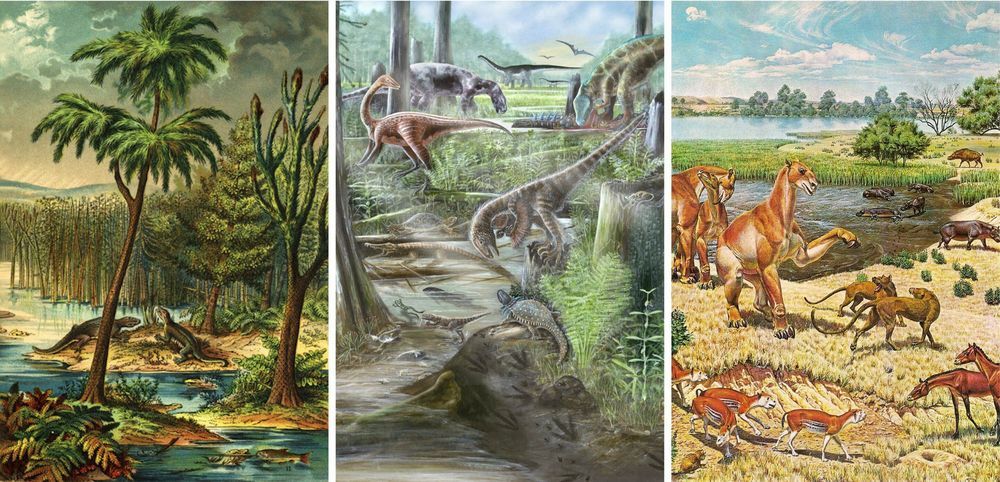

In the past few decades, a lethal disease has decimated populations of frogs and other amphibians worldwide, even driving some species to extinction. Yet other amphibians resisted the epidemic. Based on previous research, scientists at the INDICASAT AIP, Smithsonian and collaborating institutions knew that skin bacteria could be protecting the animals by producing fungi-fighting compounds. However, this time they decided to explore these as potential novel antifungal sources for the benefit of humans and amphibians.

“Amphibians inhabit humid places favoring the growth of fungi, coexisting with these and other microorganisms in their environment, some of which can be pathogenic,” said Smithsonian scientist Roberto Ibáñez, one of the authors of the study published in Scientific Reports. “As a result of evolution, amphibians are expected to possess chemical compounds that can inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria and fungi.”

The team first travelled to the Chiriquí highlands in Panama, where the chytrid fungus, responsible for the disease chytridiomycosis, has severely affected amphibian populations. They collected samples from seven frog species to find out what kind of skin bacteria they harbored.