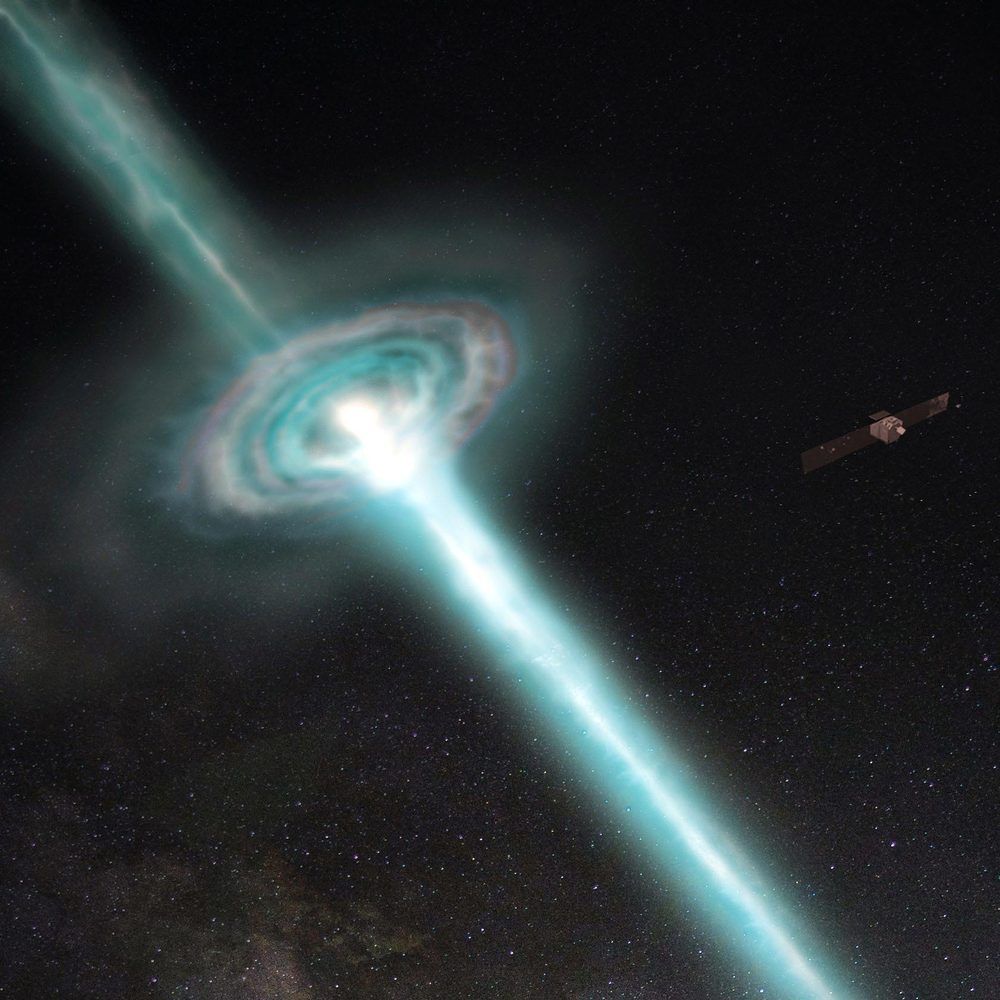

In 2019, the MAGIC telescopes detected the first Gamma Ray Burst at very high energies. This was the most intense gamma-radiation ever obtained from such a cosmic object. But the GRB data have more to offer: with further analyses, the MAGIC scientists could now confirm that the speed of light is constant in vacuum — and not dependent on energy. So, like many other tests, GRB data also corroborate Einstein’s theory of General Relativity. The study has now been published in Physical Review Letters.

Einstein’s general relativity (GR) is a beautiful theory that explains how mass and energy interact with space-time, creating a phenomenon commonly known as gravity. GR has been tested and retested in various physical situations and over many different scales, and, postulating that the speed of light is constant, it always turned out to outstandingly predict the experimental results. Nevertheless, physicists suspect that GR is not the most fundamental theory, and that there might exist an underlying quantum mechanical description of gravity, referred to as quantum gravity (QG).

Some QG theories consider that the speed of light might be energy dependent. This hypothetical phenomenon is called Lorentz invariance violation (LIV). Its effects are thought to be too tiny to be measured, unless they are accumulated over a very long time. So how to achieve that? One solution is using signals from astronomical sources of gamma rays. Gamma-ray bursts (GRBs) are powerful and far away cosmic explosions, which emit highly variable, extremely energetic signals. They are thus excellent laboratories for experimental tests of QG. The higher energy photons are expected to be more influenced by the QG effects, and there should be plenty of those; these travel billions of years before reaching Earth, which enhances the effect.