Ut ohh.

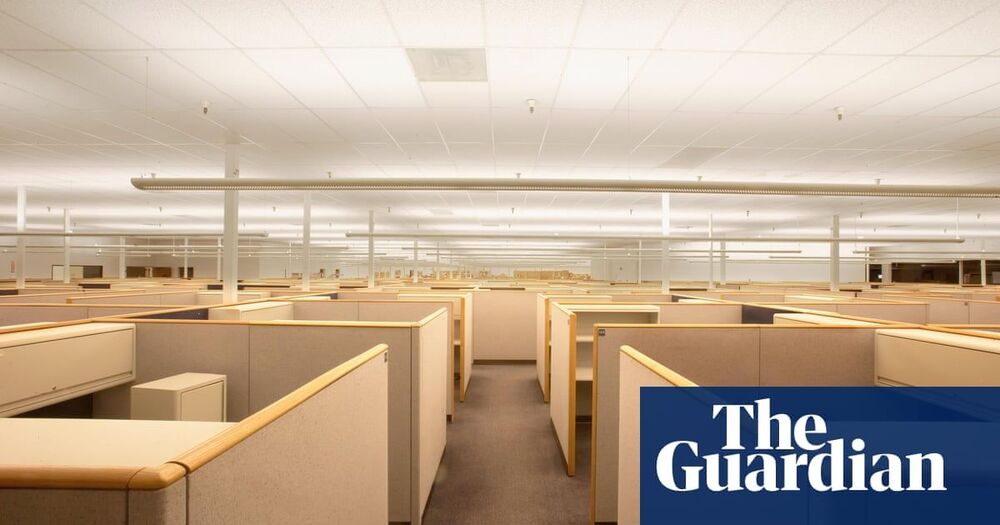

The middle and working classes have seen a steady decline in their fortunes. Sending jobs to foreign countries, the hollowing out of the manufacturing sector, pivoting toward a service economy and the weakening of unions have been blamed for the challenges faced by a majority of Americans.

There’s an interesting, compelling and alternative explanation. According to a new academic research study, automation technology has been the primary driver in U.S. income inequality over the past 40 years. The report, published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, claims that 50% to 70% of changes in U.S. wages, since 1980, can be attributed to wage declines among blue-collar workers who were replaced or degraded by automation.

Artificial intelligence, robotics and new sophisticated technologies have caused a wide chasm in wealth and income inequality. It looks like this issue will accelerate. For now, college-educated, white-collar professionals have largely been spared the fate of degreeless workers. People with a postgraduate degree saw their salaries rise, while “low-education workers declined significantly.” According to the study, “The real earnings of men without a high-school degree are now 15% lower than they were in 1980.”