Nader Al-Naji started mining bitcoin in his Princeton dorm in 2013. Now, he’s working on a stable cryptocurrency that be believes could actually replace money.

Category: economics

Reports began surfacing in the media earlier this week that Finland was scrapping its much-discussed basic income experiment. The country began paying 2,000 unemployed Finns a basic income of €560 ($678) a month in January of 2017.

Articles this week ran headlines implying that Finland had decided to halt the experiment, implying that it had become unpopular.” The eagerness of the government is evaporating. They rejected extra funding [for it],” said Olli Kangas, the leader of the research team at Kela (Social Insurance Institution of Finland), told the BBC.

In actual fact, Finland is continuing its basic income plan until the end of 2018, as it had initially planned. Yes, it’s true that it won’t be extended past that date — but there hasn’t been any official word from the Finnish government that the experiment has been a failure. If anything, the government appears to be intent on studying the effects of the two-year program but believe they can only do so after it’s finished.

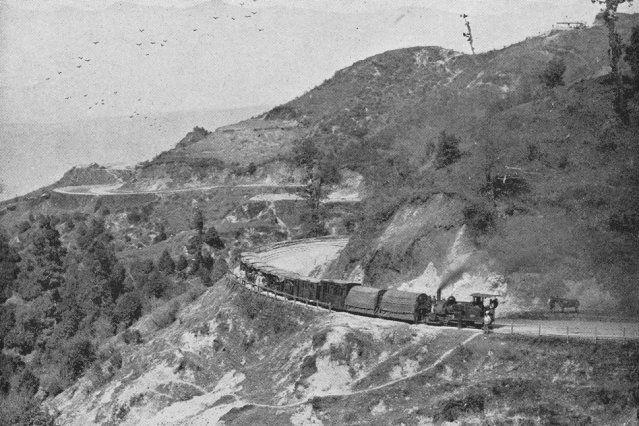

Before 1870, India barely had railroads. It didn’t have many canals either, and only a small percentage of the population lived along the three main rivers. So when goods needed to be transported, people used steer, which could pull freight about 20 miles per day.

But the British, India’s colonial rulers, started building rail lines, and then built some more. By 1930, there were more than 40,000 miles of railroads in India, and goods could be shipped about 400 miles a day.

The result? As MIT economist David Donaldson shows in a newly published study on the economic impact of building infrastructure, railroads fostered commerce that raised real agricultural income by 16 percent.

Nuclear power plants typically run either at full capacity or not at all. Yet the plants have the technical ability to adjust to the changing demand for power and thus better accommodate sources of renewable energy such as wind or solar power.

Researchers from the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology recently explored the benefits of doing just that. If nuclear plants generated power in a more flexible manner, the researchers say, the plants could lower electricity costs for consumers, enable the use of more renewable energy, improve the economics of nuclear energy and help reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The team explored technical constraints on flexible operations at nuclear power plants and introduced a new way to model how those challenges affect how power systems operate. “Flexible nuclear power operations are a ‘win-win-win,’ lowering power system operating costs, increasing revenues for nuclear plant owners and significantly reducing curtailment of renewable energy,” wrote the team in an Applied Energy article published online on April 24.

The World Economic Forum is an independent international organization committed to improving the state of the world by engaging business, political, academic and other leaders of society to shape global, regional and industry agendas. Incorporated as a not-for-profit foundation in 1971, and headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland, the Forum is tied to no political, partisan or national interests.

Researchers in artificial intelligence can stand to make a ton of money. But this week, we actually know just how much some A.I. experts are being paid — and it’s a lot, even at a nonprofit.

OpenAI, a nonprofit research lab, paid its lead A.I. expert, Ilya Sutskever, more than $1.9 million in 2016, according to a recent public tax filing. Another researcher, Ian Goodfellow, made more than $800,000 that year, even though he was only hired in March, the New York Times reported.

As the publication points out, the figures are eye-opening and offer a bit of insight on how much A.I. researchers are being paid across the globe. Normally, this kind of data isn’t readily accessible. But since OpenAI is a nonprofit organization, it’s required by law to make these figures public.

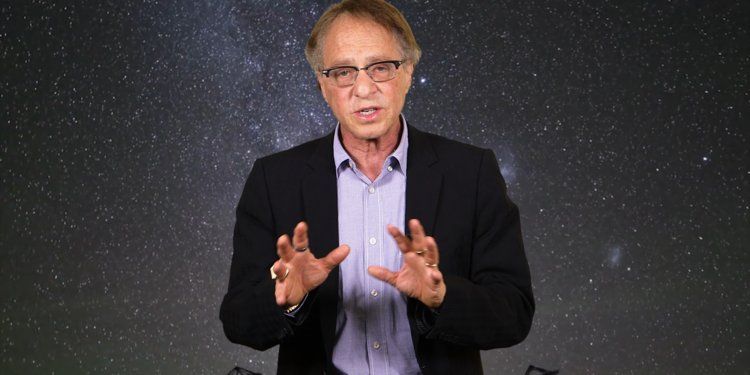

- Basic income will be widespread by the 2030s, according to Google futurist and director of engineering Ray Kurzweil.

- Kurzweil is known for making seemingly wild predictions. In 2016, he predicted that by 2029, medical technology will add an extra year to human life expectancies on an annual basis.

- ” We’re going to have more and more powerful technology to keep our physical bodies going. We’ll think, ‘Wow, back in 2018, people only had one body, and they couldn’t back up their mind file,’” he said onstage at TED.

As it becomes apparent that artificial intelligence will replace ever-more jobs in the coming years, a growing number of politicians, nonprofits, and Silicon Valley entrepreneurs have started thinking about how we’ll cope with a world in which not everyone can — or needs to — work.

Basic income experiments, in which people are given a regular salary just to live, no strings attached, are popping up all over Europe, Africa, and North America.

That, he said, will lead to new forms of expression, such as music, that will be as different from today’s communication as current human expression is from that of primates.

Asked how the U.S. and other countries would pay for a basic income, given existing large deficits, Kurzweil predicted that massive deflation would make goods much cheaper.

Separately: Kurzweil debuted a new Google project called “Talk to Books,” a new free tool that allows people to use their voice to ask a question and that will go find the best answers from hundreds of thousands of books. Unlike traditional search, it is based on semantics, not keywords.

Before I started working on real-world robots, I wrote about their fictional and historical ancestors. This isn’t so far removed from what I do now. In factories, labs, and of course science fiction, imaginary robots keep fueling our imagination about artificial humans and autonomous machines.

Real-world robots remain surprisingly dysfunctional, although they are steadily infiltrating urban areas across the globe. This fourth industrial revolution driven by robots is shaping urban spaces and urban life in response to opportunities and challenges in economic, social, political, and healthcare domains. Our cities are becoming too big for humans to manage.

Good city governance enables and maintains smooth flow of things, data, and people. These include public services, traffic, and delivery services. Long queues in hospitals and banks imply poor management. Traffic congestion demonstrates that roads and traffic systems are inadequate. Goods that we increasingly order online don’t arrive fast enough. And the WiFi often fails our 24/7 digital needs. In sum, urban life, characterized by environmental pollution, speedy life, traffic congestion, connectivity and increased consumption, needs robotic solutions—or so we are led to believe.