LEAF attended the first Longevity and Cryopreservation Summit in Madrid recently. Here is another report from Elena Milova from the conference.

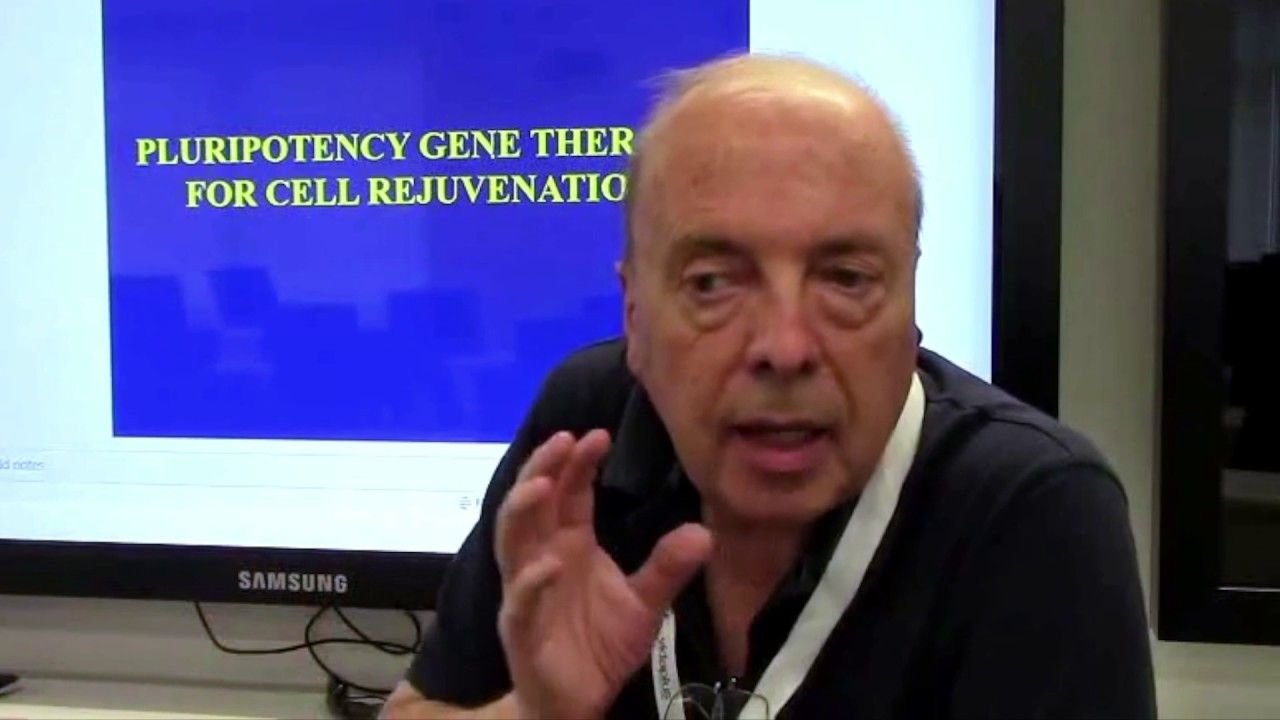

Elena Milova brings us another interesting interview from the recent International Longevity and Cryopreservation Summit where she caught up with Senior Scientist at the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET) of Argentina Dr. Rodolfo Gustavo Goya.

Dr. Goya admits he used to be a rebel from a young age. At 17 he decided he was not happy about aging and that he wanted to make a difference. He became a biochemist in the hope he could do something about age-related health deterioration and he continues to rebel against mother nature to this day. Dr. Goya has lead a number of studies on cellular reprogramming and restoration of function in important organs like the thymus and brain. He is also daring to challenge death itself by studying different aspects of cryopreservation and openly supports cryonics as a logical extension of medicine.

Dr. Goya explains his interest and motivation in aging research, as well as his views on the potential of Yamanaka factors and their limitations in relation to human rejuvenation, in this short interview.