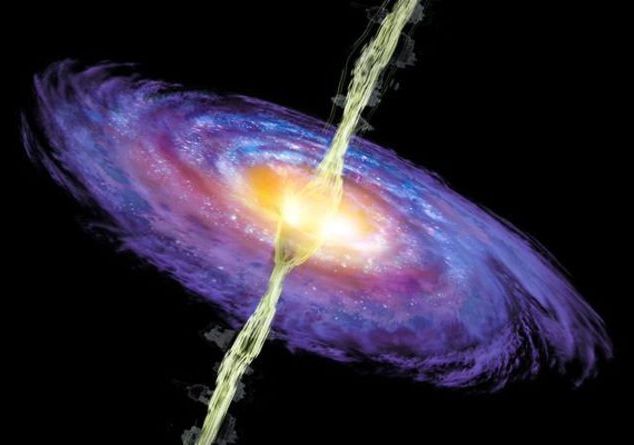

The universe bathes in a sea of light, from the blue-white flickering of young stars to the deep red glow of hydrogen clouds. Beyond the colors seen by human eyes, there are flashes of X-rays and gamma rays, powerful bursts of radio, and the faint, ever-present glow of the cosmic microwave background. The cosmos is filled with colors seen and unseen, ancient and new. But of all these, there was one color that appeared before all the others, the first color of the universe.

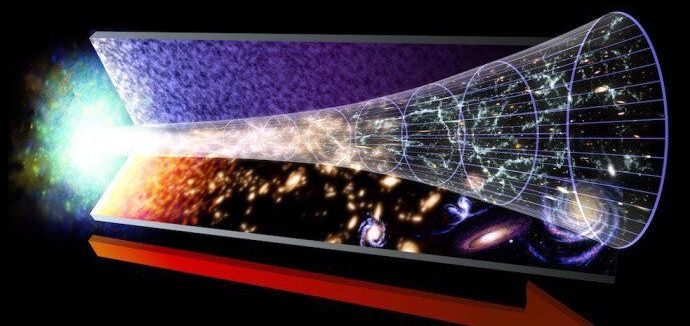

The universe began 13.8 billion years ago with the Big Bang. In its earliest moment, it was more dense and hot than it would ever be again. The Big Bang is often visualized as a brilliant flash of light appearing out of a sea of darkness, but that isn’t an accurate picture. The Big Bang didn’t explode into empty space. The Big Bang was an expanding space filled with energy.

At first, temperatures were so high that light didn’t exist. The cosmos had to cool for a fraction of a second before photons could appear. After about 10 seconds, the universe entered the photon epoch. Protons and neutrons had cooled into the nuclei of hydrogen and helium, and space was filled with a plasma of nuclei, electrons and photons. At that time, the temperature of the universe was about 1 billion degrees Kelvin.