White dwarfs are burnt out stars that can explode into supernovae, and this process might be kicked off by a black hole made of dark matter in the heart of the star.

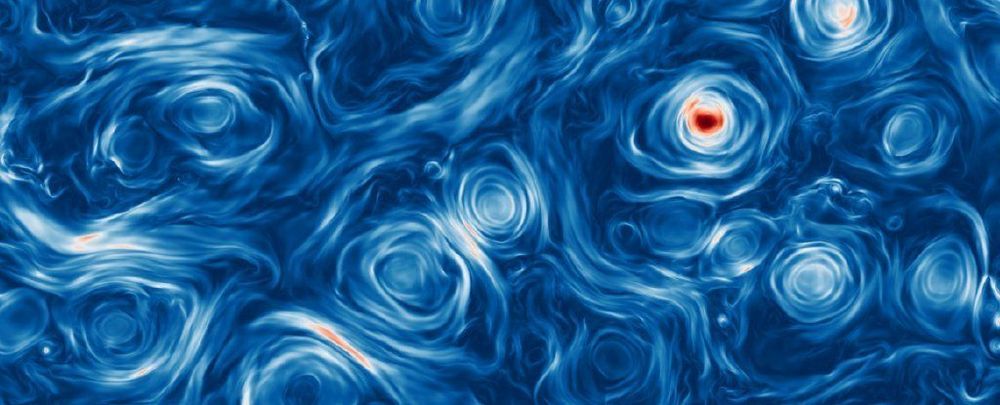

There’s some irony in the fact that the darkest objects in the sky — black holes — can be responsible for some of the Universe’s brightest light. Simulations of the magnetic fields surrounding black holes and neutron stars have now provided new insights into their astonishing brilliance.

Astrophysicists from Columbia University in New York have developed a model that shows how electrons taking a cosmic roller coaster-ride through magnetic turbulence can generate surprisingly energetic waves of radiation.

Applied to the swirling chaos surrounding dense objects such as black holes, it helps to explain why we see them glow with a ferocity that so far defies explanation.

The current Lambda CDM model may explain a great deal about the evolution and the chronology of the events that occurred in our Universe but it doesn’t paint the complete picture.

We know of the cosmic inflation that happened followed by the Big Bang itself however how these two are coherently connected has so far defied all our attempts to explain.

During the inflationary period, within less than a trillionth of a second, our universe grew from an infinitesimal point to an octillion (that’s 1 followed by 27 zeroes) times in size, which was followed by a more conventional and gradual period of expansion, nevertheless violent by our standards, which we know as the Big Bang.

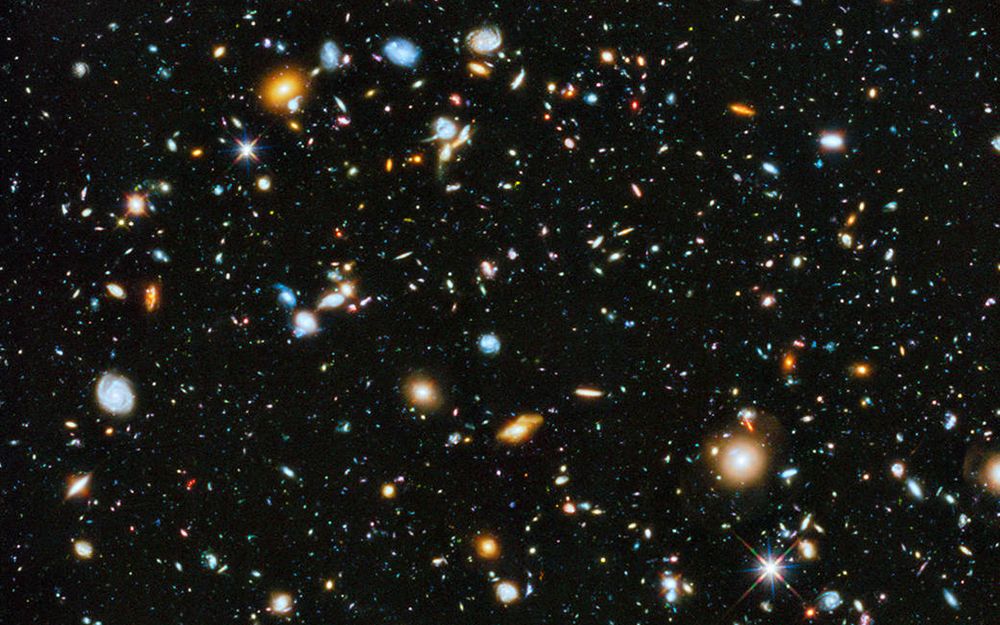

The universe is filled with billions of galaxies and trillions of stars, along with nearly uncountable numbers of planets, moons, asteroids, comets and clouds of dust and gas – all swirling in the vastness of space.

But if we zoom in, what are the building blocks of these celestial bodies, and where did they come from?

Hydrogen is the most common element found in the universe, followed by helium; together, they make up nearly all ordinary matter. But this accounts for only a tiny slice of the universe — about 5%. All the rest is made of stuff that can’t be seen and can only be detected indirectly. [From Big Bang to Present: Snapshots of Our Universe Through Time].

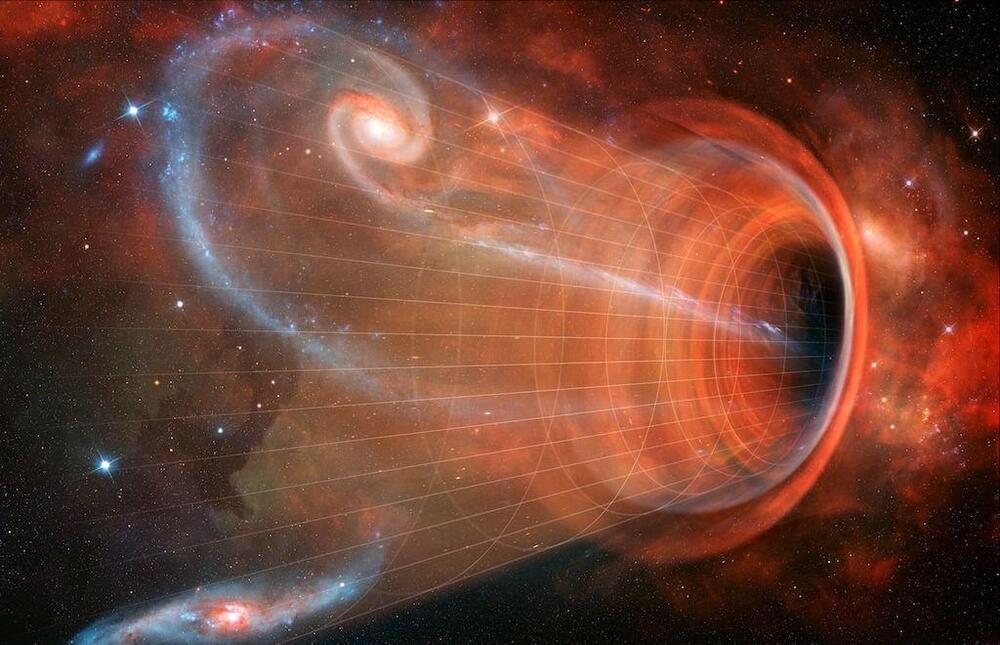

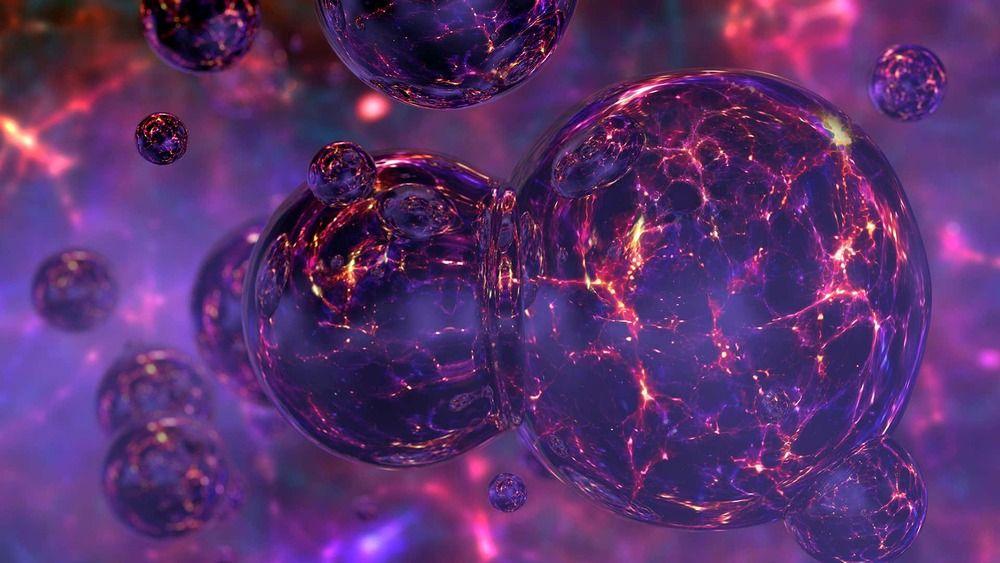

What – one vast, ancient and mysterious universe isn’t enough for you? Well, as it happens, there are others. Among physicists, it’s not controversial. Our universe is but one in an unimaginably massive ocean of universes called the multiverse.

If that concept isn’t enough to get your head around, physics describes different kinds of multiverse. The easiest one to comprehend is called the cosmological multiverse. The idea here is that the universe expanded at a mind-boggling speed in the fraction of a second after the big bang. During this period of inflation, there were quantum fluctuations which caused separate bubble universes to pop into existence and themselves start inflating and blowing bubbles. Russian physicist Andrei Linde came up with this concept, which suggests an infinity of universes no longer in any causal connection with one another – so free to develop in different ways.

Cosmic space is big – perhaps infinitely so. Travel far enough and some theories suggest you’d meet your cosmic twin – a copy of you living in a copy of our world, but in a different part of the multiverse. String theory, which is a notoriously theoretical explanation of reality, predicts a frankly meaninglessly large number of universes, maybe 10 to the 500 or more, all with slightly different physical parameters.