Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, an international team of astronomers has performed observations of HSC J120505.09−000027.9—the most distant red quasar so far detected and found that it showcases an extended emission of ionized carbon. The finding is reported in a paper published January 4 on arXiv.org.

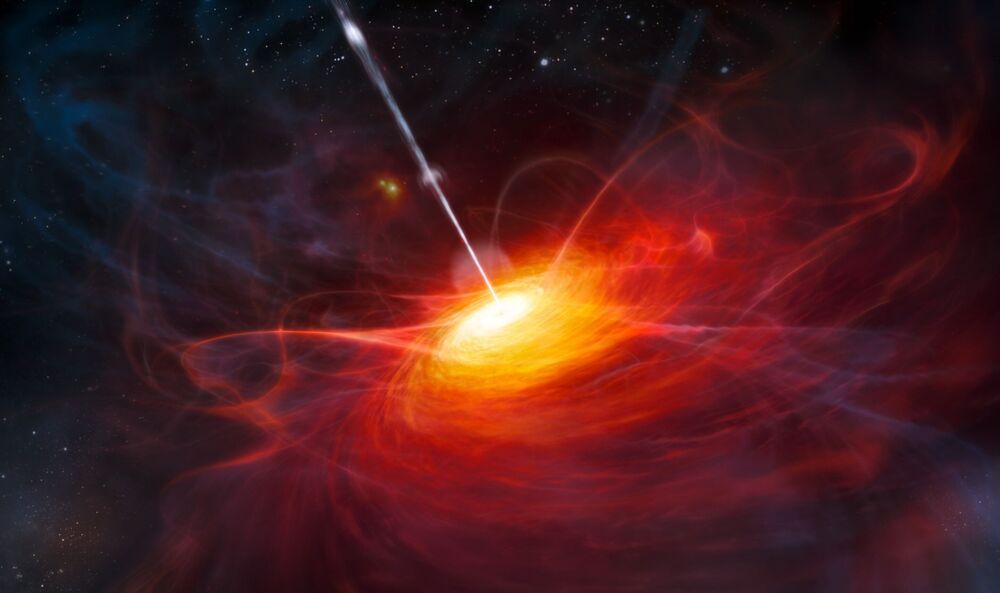

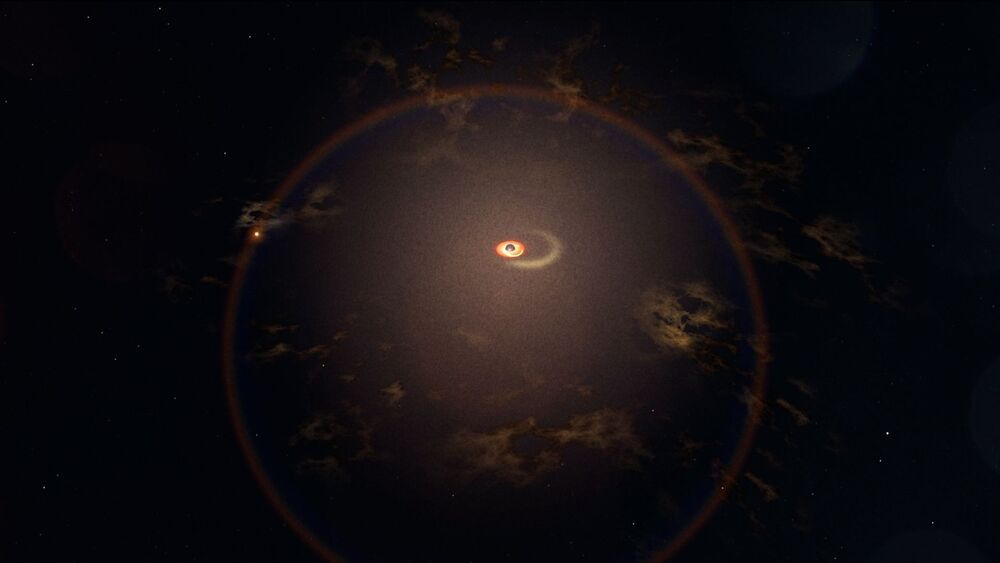

Quasars, or quasi–stellar objects (QSOs), are extremely luminous active galactic nuclei (AGN) containing supermassive central black holes with accretion disks. Their redshifts are measured from the strong spectral lines that dominate their visible and ultraviolet spectra. Some QSOs are dust-reddened, hence dubbed red quasars. These objects have a non-negligible amount of dust extinction, but are not completely obscured.

Astronomers are especially interested in studying high-redshift quasars (at redshift higher than 5.0) as they are the most luminous and most distant compact objects in the observable universe. Spectra of such QSOs can be used to estimate the mass of supermassive black holes that constrain the evolution and formation models of quasars. Therefore, high-redshift quasars could serve as a powerful tool to probe the early universe.