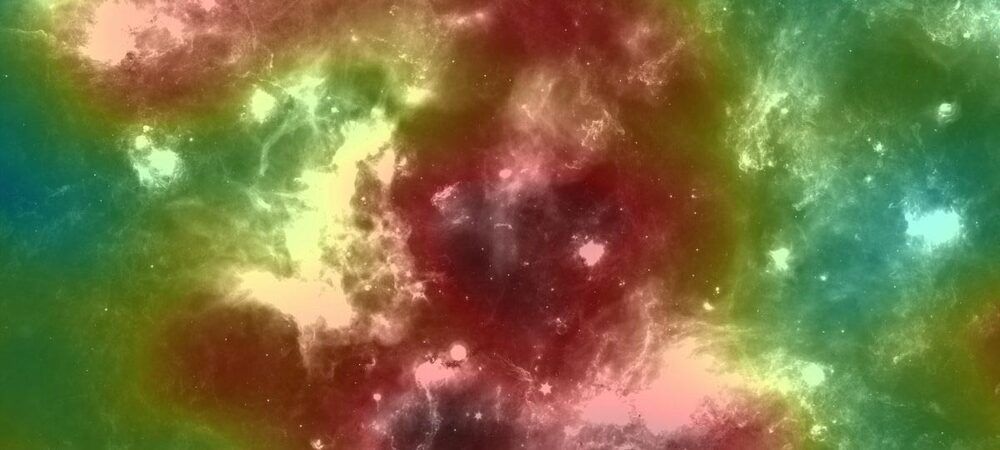

Researchers using NASA’s upcoming James Webb Space Telescope will map and model the core of nearby galaxy Centaurus A.

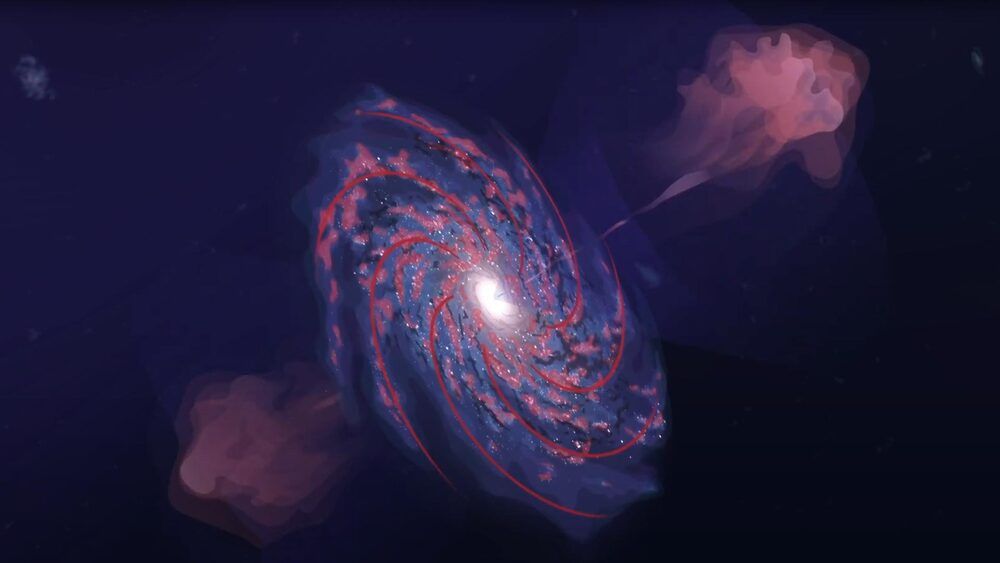

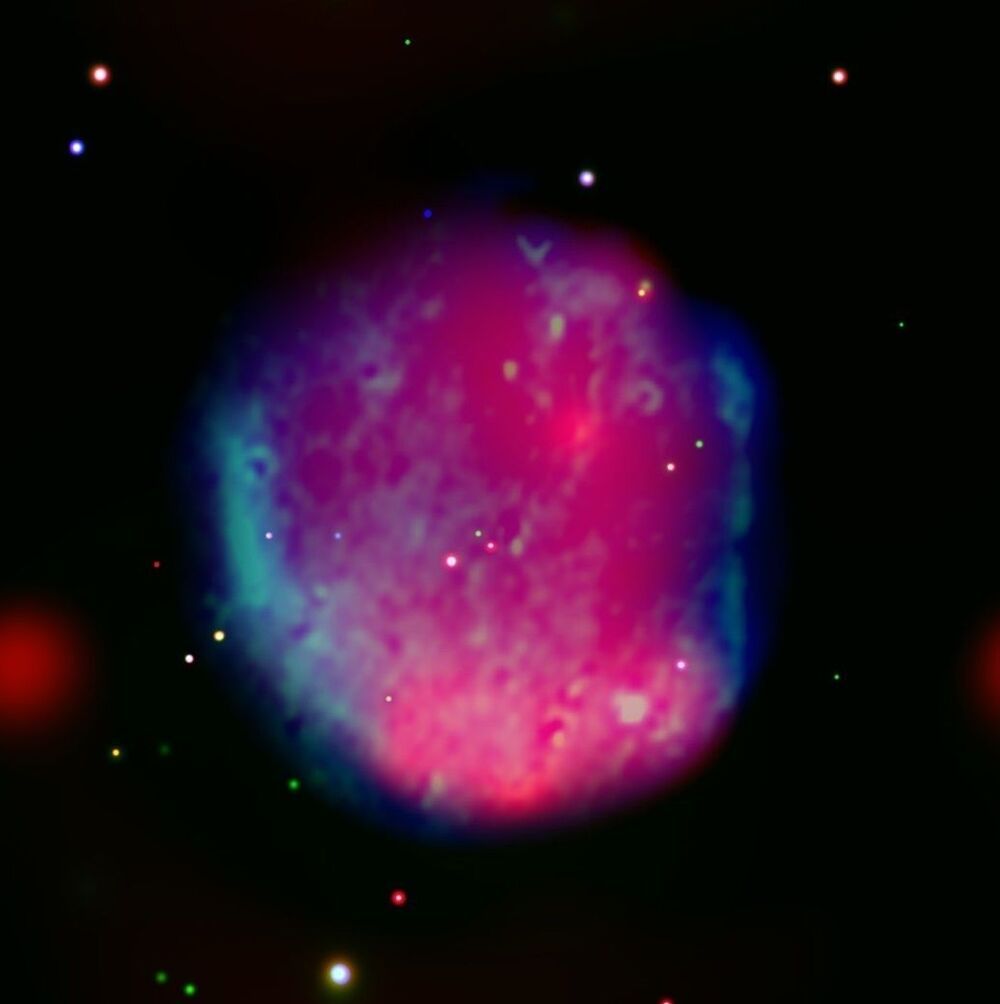

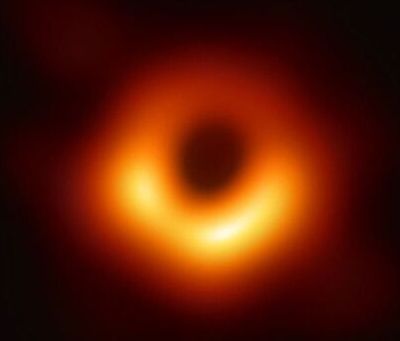

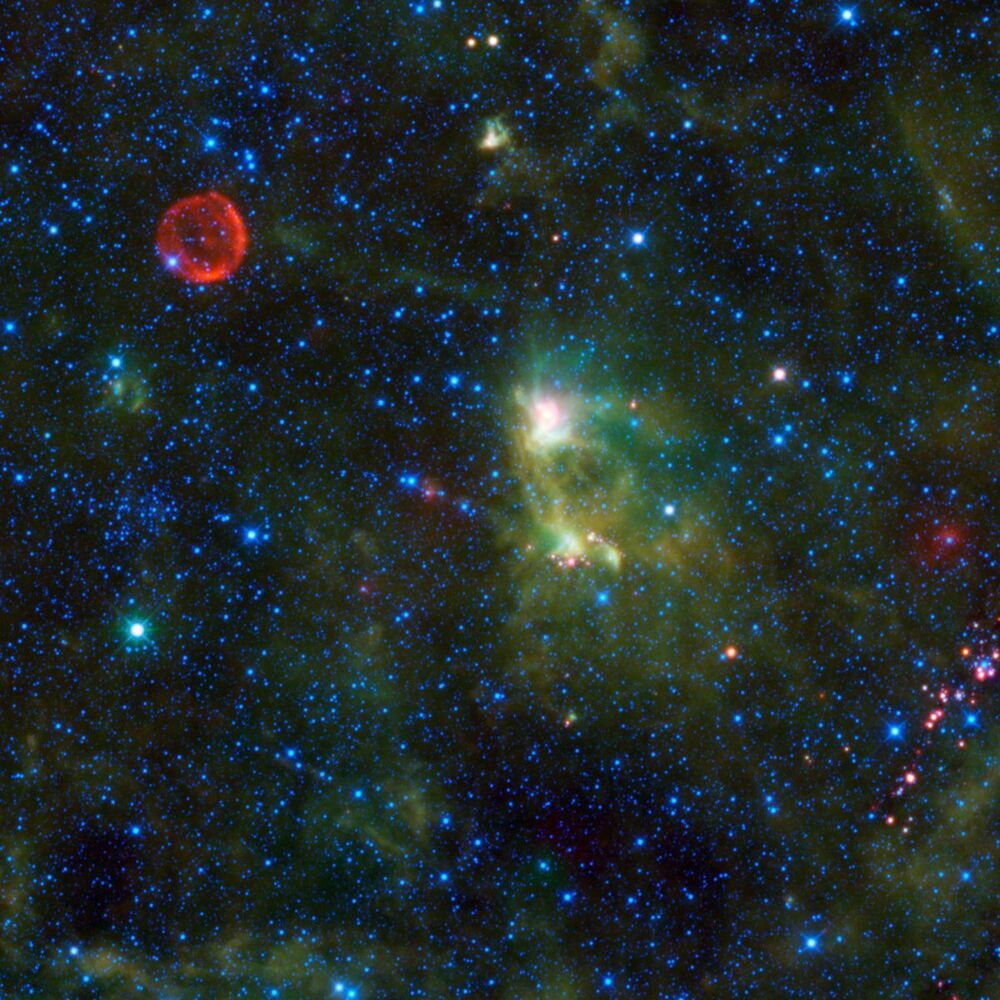

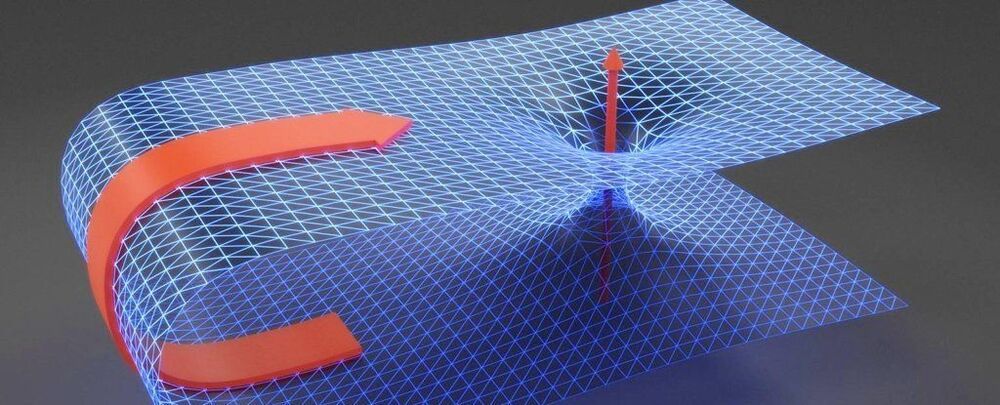

As technology has improved over the centuries, so have astronomers’ observations of nearby galaxy Centaurus A. They have peeled back its layers like an onion to discover that its wobbly shape is the result of two galaxies that merged more than 100 million years ago. It also has an active supermassive black hole, known as an active galactic nucleus, at its heart that periodically sends out twin jets. Despite these advancements, Centaurus A’s dusty core is still quite mysterious. Webb’s high-resolution infrared data will allow a research team to very precisely reveal all that lies at the center.