A new theory explains the seemingly irreversible arrow of time while yielding insights into entropy, quantum computers, black holes, and the past-future divide.

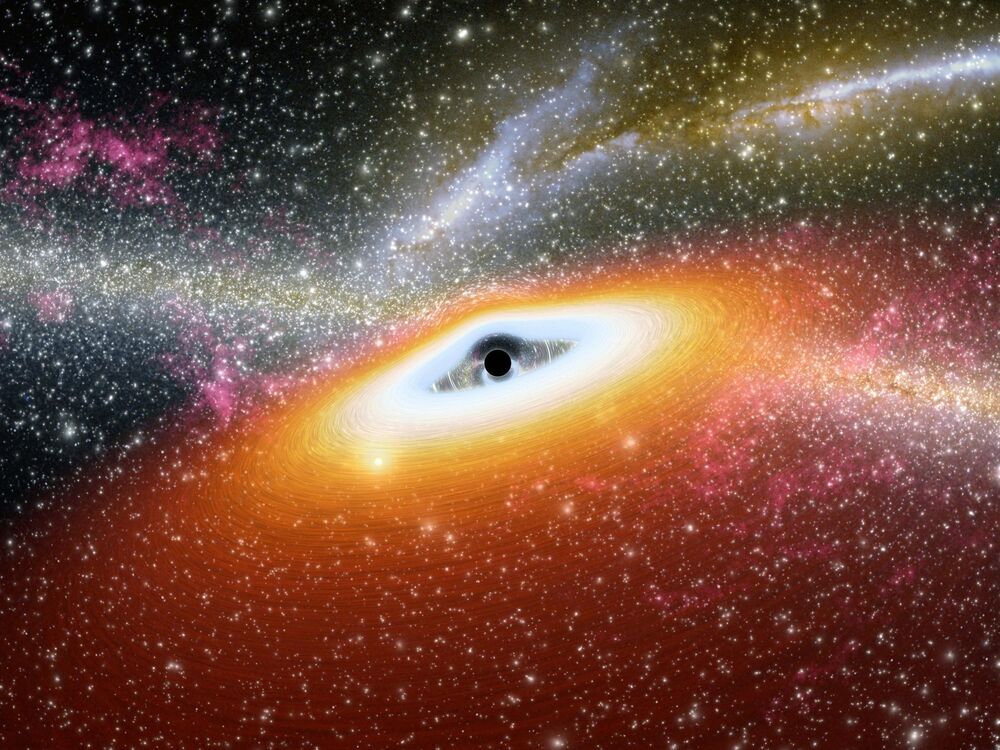

There are certain rules that even the most extreme objects in the universe must obey. A central law for black holes predicts that the area of their event horizons — the boundary beyond which nothing can ever escape — should never shrink. This law is Hawking’s area theorem, named after physicist Stephen Hawking, who derived the theorem in 1971.

Fifty years later, physicists at MIT and elsewhere have now confirmed Hawking’s area theorem for the first time, using observations of gravitational waves. Their results appear today in Physical Review Letters.

New research shows how the fundamental law of conservation of charge could break down near a black hole.

Singularities, such as those at the centre of black holes, where density becomes infinite, are often said to be places where physics ‘breaks down’. However, this doesn’t mean that ‘anything’ could happen, and physicists are interested in which laws could break down, and how.

Now, a research team from Imperial College London, the Cockcroft Institute and Lancaster University have proposed a way that singularities could violate the law of conservation of charge. Their theory is published in Annalen der Physik.

“In physics, we often say that exceptional discoveries require exceptionally strong evidence.”

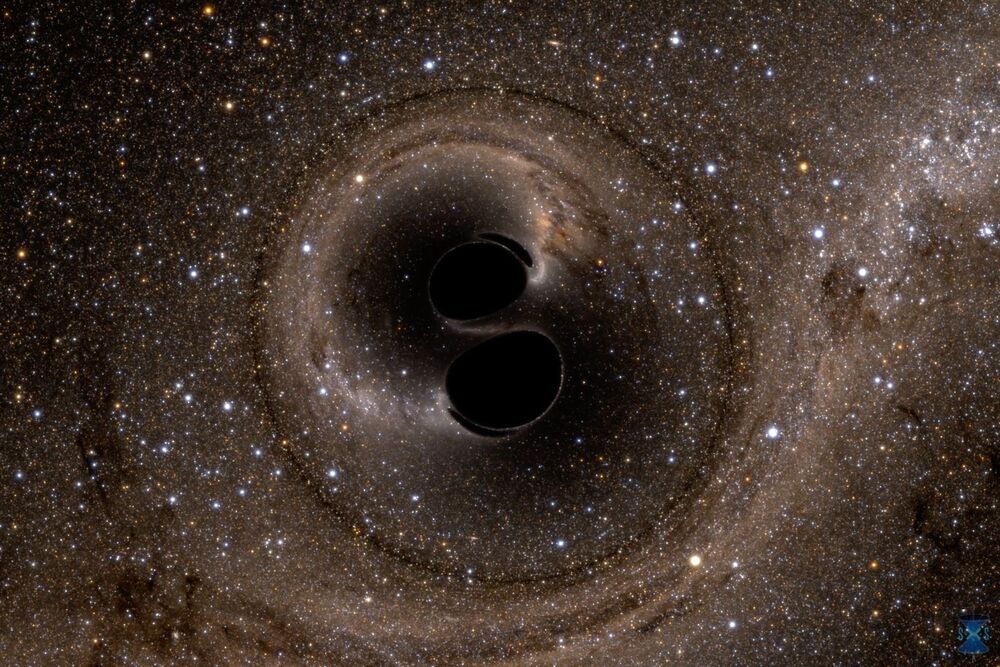

Within the space of ten days, LIGO detected gravitational waves that prove black holes can form binaries with neutron stars.

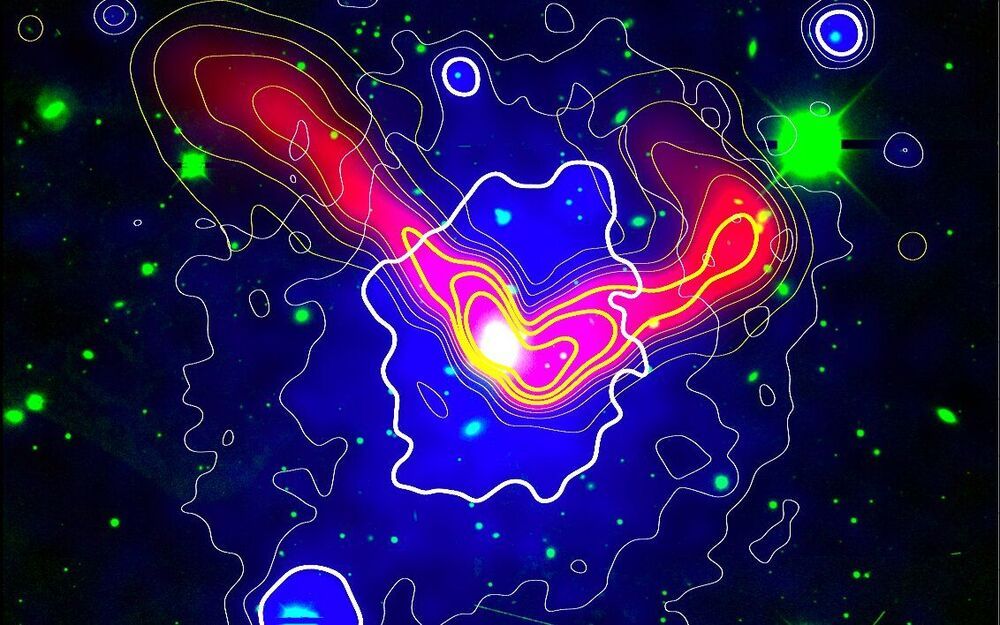

An international group of astronomers has created images with never-before-seen detail of a galaxy cluster with a black hole at its center, traveling at high speed along an intergalactic “road of matter.” The findings also support existing theories of the origins and evolution of the universe.

The concept that roads of thin gas connect clusters of galaxies across the universe has been difficult to prove until recently, because the matter in these ‘roads’ is so sparse it eluded the gaze of even the most sensitive instruments. Following the 2020 discovery of an intergalactic thread of gas at least 50 million light-years long, scientists have now developed images with an unprecedented level of detail of the Northern Clump—a cluster of galaxies found on this thread.

By combining imagery from various sources including CSIRO’s ASKAP radio telescope, SRG/eROSITA, XMM-Newton and Chandra satellites, and DECam optical data, the scientists could make out a large galaxy at the center of the clump, with a black hole at its center.

Mix pair is “elusive missing piece of the family picture of compact object mergers.”

A long time ago, in two galaxies about 900 million light-years away, two black holes each gobbled up their neutron star companions, triggering gravitational waves that finally hit Earth in January 2020.

Discovered by an international team of astrophysicists including Northwestern University researchers, two events — detected just 10 days apart — mark the first-ever detection of a black hole merging with a neutron star. The findings will enable researchers to draw the first conclusions about the origins of these rare binary systems and how often they merge.

A team led by astronomers at UC Santa Barbara have confirmed the existence of an elusive new type of supernova.

A worldwide team led by UC Santa Barbara scientists at Las Cumbres Observatory has discovered the first convincing evidence for a new type of stellar explosion — an electron-capture supernova. While they have been theorized for 40 years, real-world examples have been elusive. They are thought to arise from the explosions of massive super-asymptotic giant branch (SAGB) stars, for which there has also been scant evidence. The discovery, published in Nature Astronomy, also sheds new light on the thousand-year mystery of the supernova from A.D. 1054 that was visible all over the world in the daytime, before eventually becoming the Crab Nebula.

Historically, supernovae have fallen into two main types: thermonuclear and iron-core collapse. A thermonuclear supernova is the explosion of a white dwarf star after it gains matter in a binary star system. These white dwarfs are the dense cores of ash that remain after a low-mass star (one up to about 8 times the mass of the sun) reaches the end of its life. An iron core-collapse supernova occurs when a massive star — one more than about 10 times the mass of the sun — runs out of nuclear fuel and its iron core collapses, creating a black hole or neutron star. Between these two main types of supernovae are electron-capture supernovae. These stars stop fusion when their cores are made of oxygen, neon and magnesium; they aren’t massive enough to create iron.

The Large Hadron Collider has a lot of tasks ahead of it. Next stop: investigating the Big Bang.

The truth is, we don’t really know because it takes huge amounts of energy and precision to recreate and understand the cosmos on such short timescales in the lab.

But scientists at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN, Switzerland aren’t giving up.

Now our LHCb experiment has measured one of the smallest differences in mass between two particles ever, which will allow us to discover much more about our enigmatic cosmic origins.

Submillimeter galaxies (SMGs) are a class of the most luminous, distant, and rapidly star-forming galaxies known and can shine brighter than a trillion Suns (about one hundred times more luminous in total than the Milky Way). They are generally hard to detect in the visible, however, because most of their ultraviloet and optical light is absorbed by dust which in turn is heated and radiates at submillimeter wavelengths—the reason they are called submillimeter galaxies. The power source for these galaxies is thought to be high rates of star formation, as much as one thousand stars per year (in the Milky Way, the rate is more like one star per year). SMGs typically date from the early universe; they are so distant that their light has been traveling for over ten billion years, more than 70% of the lifetime of the universe, from the epoch about three billion years after the big bang. Because it takes time for them to have evolved, astronomers think that even a billion years earlier they probably were actively making stars and influencing their environments, but very little is known about this phase of their evolution.

SMGs have recently been identified in galaxy protoclusters, groups of dozens of galaxies in the universe when it was less than a few billion years old. Observing massive SMGs in these distant protoclusters provides crucial details for understanding both their early evolution and that of the larger structures to which they belong. CfA astronomers Emily Pass and Matt Ashby were members of a team that used infrared and optical data from the Spitzer IRAC and Gemini-South instruments, respectively, to study a previosly identified protocluster, SPT2349-56, in the era only 1.4 billion years after the big bang. The protocluster was spotted by the South Pole Telescope millimeter wavelengths and then observed in more detail with Spitzer, Gemini, and the ALMA submillimeter array.

The protocluster contains a remarkable concentration of fourteen SMGs, nine of which were detected by these optical and infrared observations. The astronomers were then able to estimate the stellar masses, ages, and gas content in these SMGs, as well as their star formation histories, a remarkable acheievment for such distant objects. Among other properties of the protocluster, the scientists deduce that its total mass is about one trillion solar-masses, and its galaxies are making stars in a manner similar to star formation processes in the current universe. They also conclude that the whole ensemble is probably in the midst of a colossal merger.