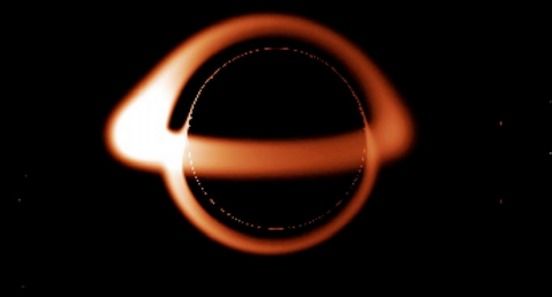

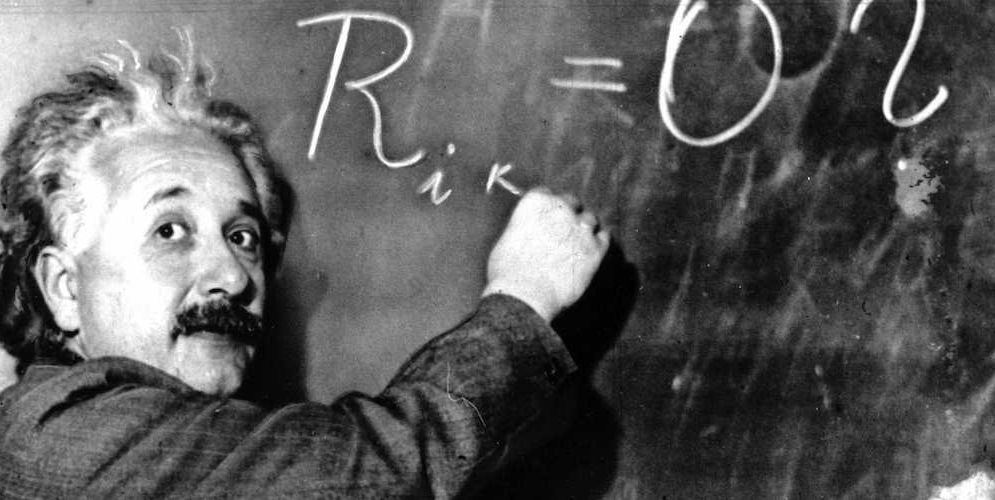

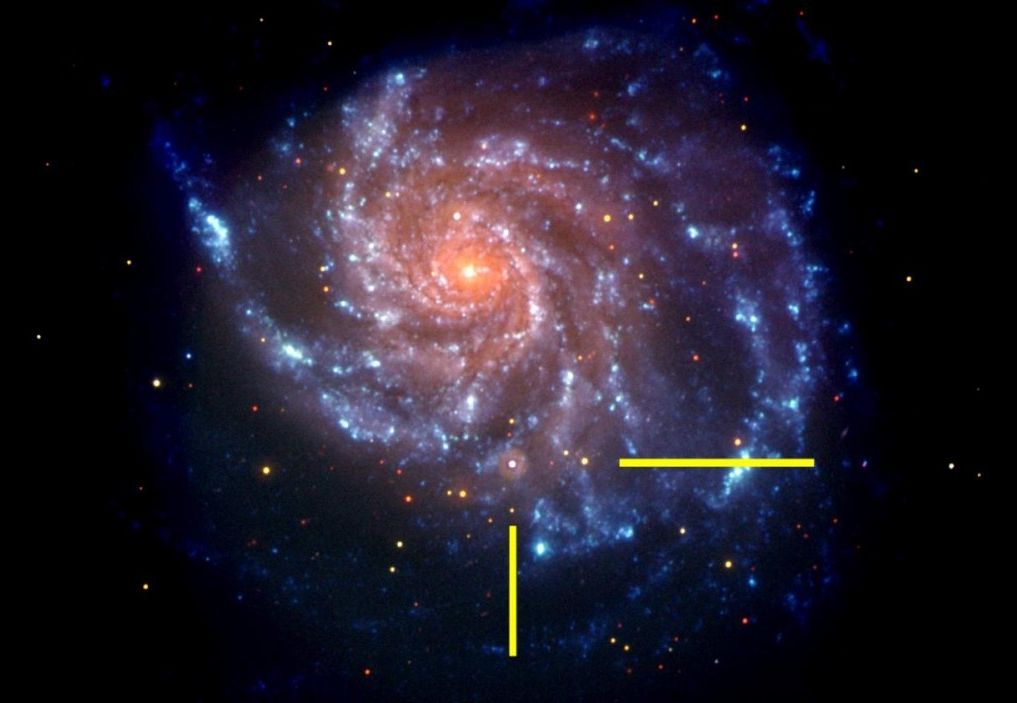

In principle, nothing that enters a black hole can leave the black hole. This has considerably complicated the study of these mysterious bodies, which generations of physicists have debated since 1916, when their existence was hypothesized as a direct consequence of Einstein’s Theory of Relativity. There is, however, some consensus in the scientific community regarding black hole entropy—a measure of the inner disorder of a physical system—because its absence would violate the second law of thermodynamics. In particular, Jacob Bekenstein and Stephen Hawking have suggested that the entropy of a black hole is proportional to its area, rather than its volume, as would be more intuitive. This assumption also gives rise to the “holography” hypothesis of black holes, which (very roughly) suggests that what appears to be three-dimensional might, in fact, be an image projected onto a distant two-dimensional cosmic horizon, just like a hologram, which, despite being a two-dimensional image, appears to be three-dimensional.

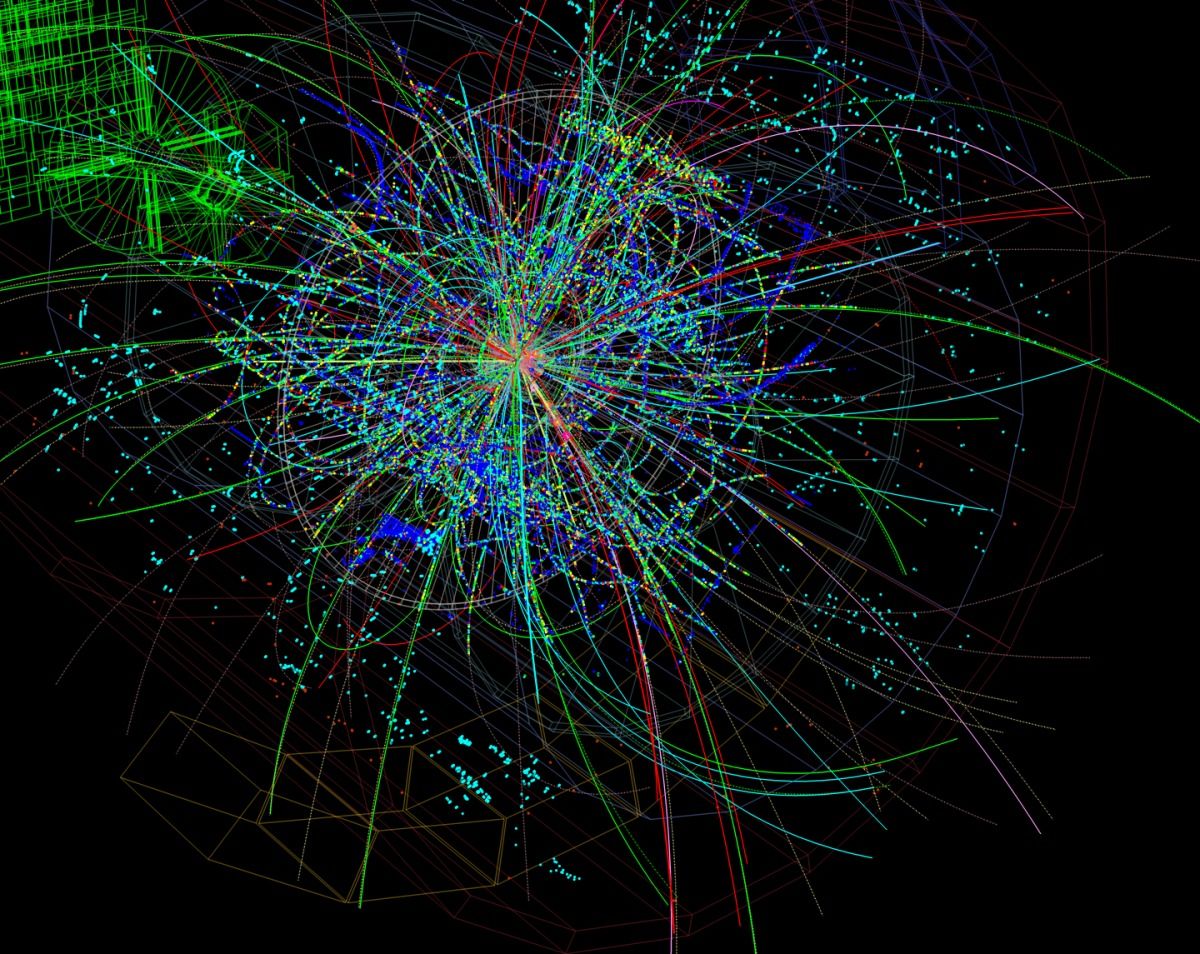

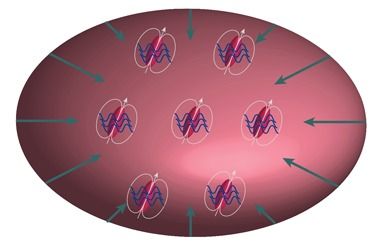

As we cannot see beyond the event horizon (the outer boundary of the back hole), the internal microstates that define its entropy are inaccessible. So how is it possible to calculate this measure? The theoretical approach adopted by Hawking and Bekenstein is semiclassical (a sort of hybrid between classical physics and quantum mechanics) and introduces the possibility (or necessity) of adopting a quantum gravity approach in these studies in order to obtain a more fundamental comprehension of the physics of black holes.

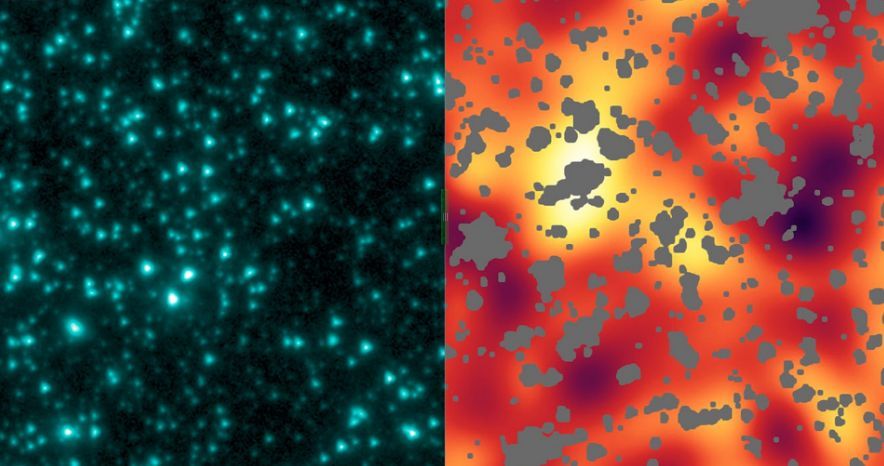

Planck’s length is the (tiny) dimension at which space-time stops being continuous as we see it, and takes on a discrete graininess made up of quanta, the “atoms” of space-time. The universe at this dimension is described by quantum mechanics. Quantum gravity is the field of enquiry that investigates gravity in the framework of quantum mechanics. Gravity has been very well described within classical physics, but it is unclear how it behaves at the Planck scale.