A paper submitted for publication just two weeks ago could prove the “multiverse” theory which Hawking loved.

Silke Weinfurtner is trying to build the universe from scratch. In a physics lab at the University of Nottingham—close to the Sherwood forest of legendary English outlaw Robin Hood—she and her colleagues will work with a huge superconducting coil magnet, 1 meter across. Inside, there’s a small pool of liquid, whose gentle ripples stand to mimic the matter fluctuations that gave rise to the structures we observe in the cosmos.

Weinfurtner isn’t an evil genius hell-bent on creating a world of her own to rule. She just wants to understand the origins of the one we already have.

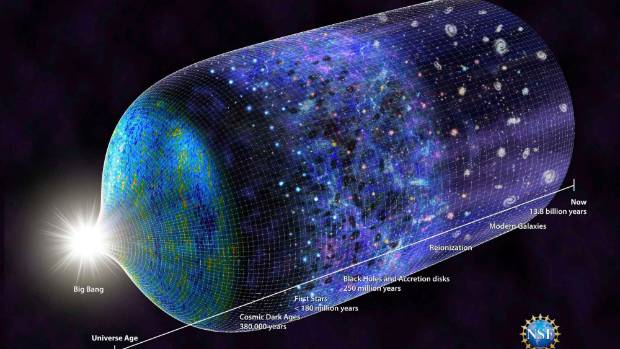

The Big Bang is by far the most popular model of our universe’s beginnings, but even its fans disagree about how it happened. The theory depends on the existence of a hypothetical quantum field that stretched the universe ultra-rapidly and uniformly in all directions, expanding it by a huge factor in a fraction of a second: a process dubbed inflation. But that inflation or the field responsible for it—the inflaton—is impossible to prove directly. Which is why Weinfurtner wants to mimic it in a lab.

An analysis of distortions in the cosmic microwave background reveals information about the gas inside large voids in space.

Galaxies tend to be the standouts in astronomy. But researchers are finding there is plenty to learn from studying cosmic voids—swaths of mostly empty space, hundreds of millions of light years across. The temperature and pressure of the gas in voids could, for example, provide clues to how energy cycles through the cosmos. David Alonso, of the University of Oxford in the UK, and colleagues have now taken one of the first steps toward determining these gas properties by analyzing how the gas distorts light from the early Universe.

The cosmic microwave background (CMB) is the first light released into the cosmos, roughly 380,000 years after the big bang. Intergalactic gas boosts the energy of photons from the CMB, and this distortion is a powerful probe of the gas in galaxy clusters. But no one has yet used it to study voids. Alonso’s team combined maps of the CMB with images of 774 cosmic voids. The researchers then deduced the properties of the gas within each void by comparing the measured energy of the CMB photons to models of the electron pressure in voids.

Such an amazing mind!

Stephen Hawking, one of the greatest minds of our lifetime, has passed away — leaving behind a lot of heartbroken science fans.

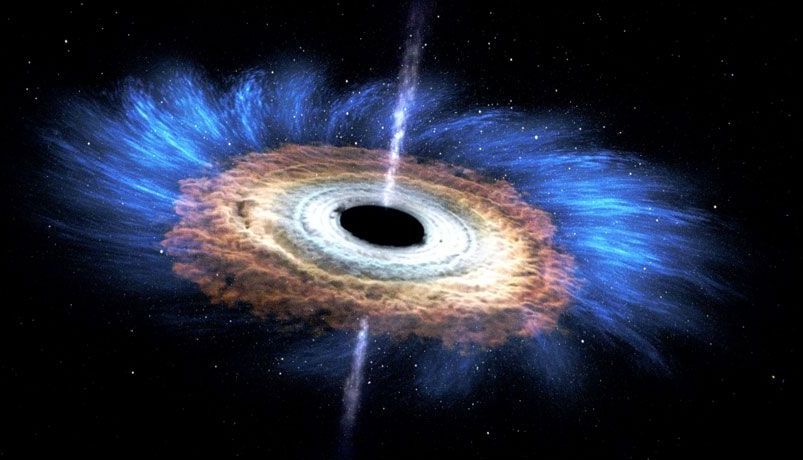

While he was publishing papers right up until the months before his death, it was in 2016 that he released one of his most talked about journal articles — a long-awaited solution to his black hole information paradox.

In other words, he’d come up with a potential explanation for how black holes can simultaneously erase information and retain it.

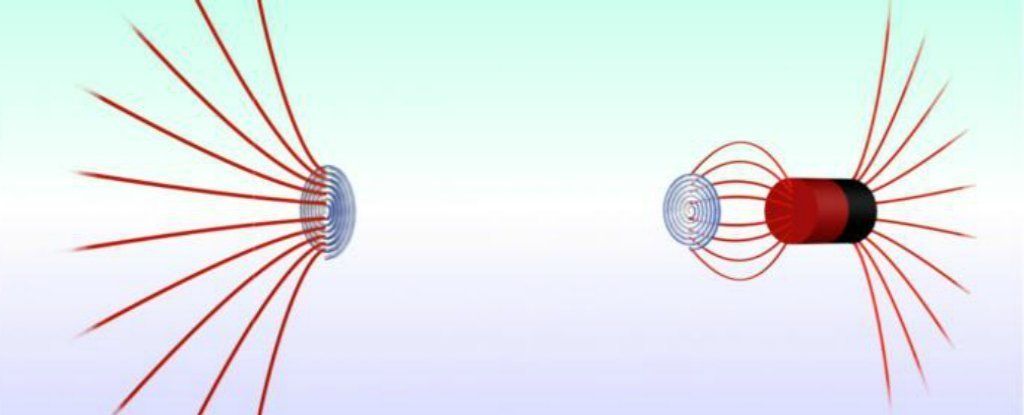

Back in 2015, researchers in Spain created a tiny magnetic wormhole for the first time ever. They used it to connect two regions of space so that a magnetic field could travel ‘invisibly’ between them.

Before you get too excited, it wasn’t the kind of gravitational wormhole that would theoretically allow humans to travel rapidly across space in science fiction TV shows and films such as Stargate, Star Trek, and Interstellar, and it wouldn’t have been able to transport matter.

But the physicists managed to create a tunnel that allowed a magnetic field to disappear at one point, and then reappear at another, which is still a pretty huge deal.

In 1935, when both quantum mechanics and Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity were young, a little-known Soviet physicist named Matvei Bronstein, just 28 himself, made the first detailed study of the problem of reconciling the two in a quantum theory of gravity. This “possible theory of the world as a whole,” as Bronstein called it, would supplant Einstein’s classical description of gravity, which casts it as curves in the space-time continuum, and rewrite it in the same quantum language as the rest of physics.

Bronstein figured out how to describe gravity in terms of quantized particles, now called gravitons, but only when the force of gravity is weak — that is (in general relativity), when the space-time fabric is so weakly curved that it can be approximated as flat. When gravity is strong, “the situation is quite different,” he wrote. “Without a deep revision of classical notions, it seems hardly possible to extend the quantum theory of gravity also to this domain.”

His words were prophetic. Eighty-three years later, physicists are still trying to understand how space-time curvature emerges on macroscopic scales from a more fundamental, presumably quantum picture of gravity; it’s arguably the deepest question in physics. Perhaps, given the chance, the whip-smart Bronstein might have helped to speed things along. Aside from quantum gravity, he contributed to astrophysics and cosmology, semiconductor theory, and quantum electrodynamics, and he also wrote several science books for children, before being caught up in Stalin’s Great Purge and executed in 1938, at the age of 31.