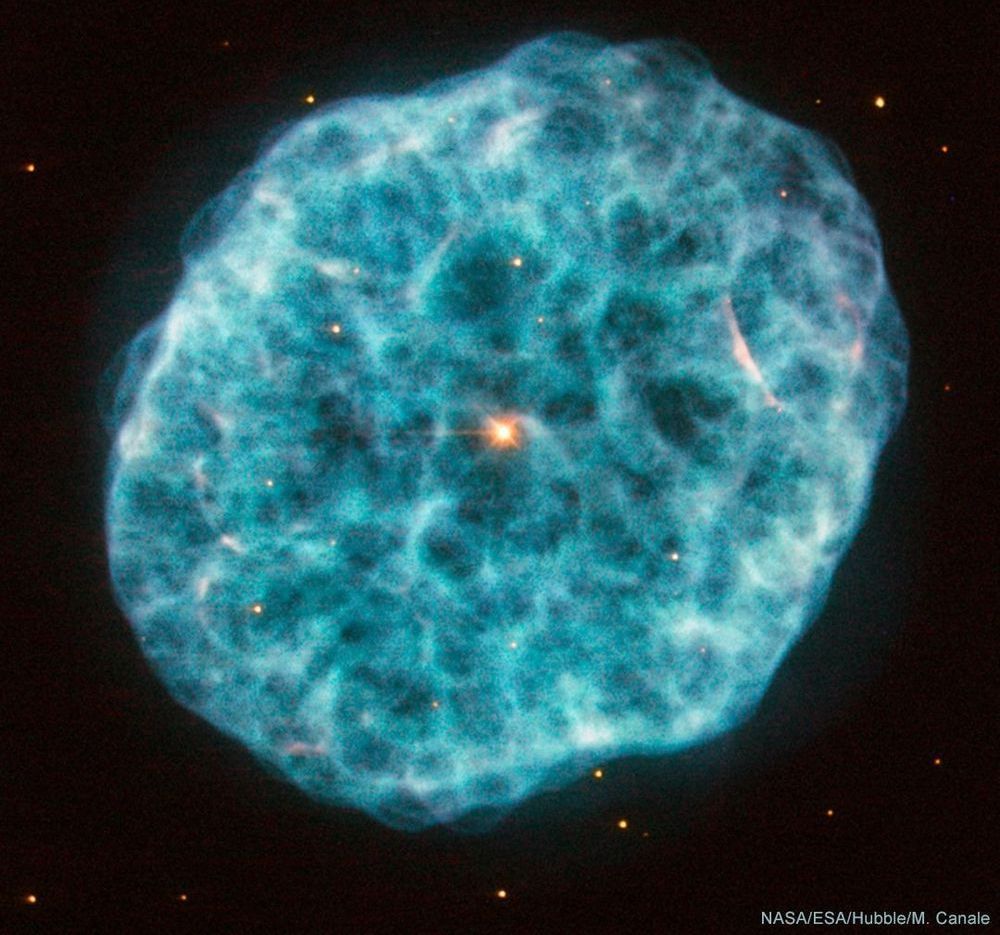

The image mosaic was created using 16 years’ worth of data from the Hubble Space Telescope, and it shows roughly 265,000 galaxies stretching back 13.3 billion years, to just 500 million years after the Big Bang.

Background: This isn’t the first Hubble deep-field image. The first one was released back in 1995, with further deep-field images following in 2003, 2004, and 2012. However, this is by far the most comprehensive. It was created by weaving together several of the previous Hubble photos. The image, dubbed the Hubble Legacy Field, represents 7,500 separate exposures. It contains about 30 times as many galaxies as the previous shots. The image above is just a section of the whole: you can see the full thing here.

A time machine: Because many of the galaxies Hubble captures are so far away, it has taken billions of years for their light to reach us. That makes the telescope a sort of time machine, letting us see galaxies as they were billions of years ago.