If you turn down the partisanship, you turn up the public understanding.

Now, another hurricane season is already underway in the Caribbean.

Our research on rainwater harvesting — a low-cost, low-tech way to collect and store rainwater — suggests this technique could be deployed across the Caribbean to improve these communities’ access to water both after storms and in everyday life.

Even before hurricanes Maria and Irma hit last September, some Caribbean islands were unable to provide reliable clean water for drinking and washing to all residents.

In recent decades, scientists have noted a surge in Arctic plant growth as a symptom of climate change. But without observations showing exactly when and where vegetation has bloomed as the world’s coldest areas warm, it’s difficult to predict how vegetation will respond to future warming. Now, researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and UC Berkeley have developed a new approach that may paint a more accurate picture of Arctic vegetation and our climate’s recent past – and future.

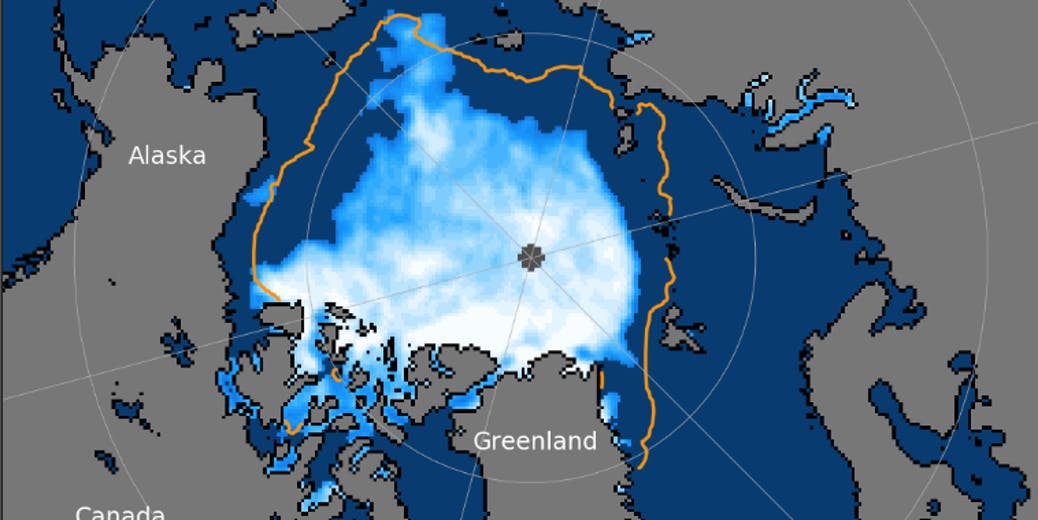

In a study published online Aug. 20 in Nature Climate Change, the researchers used satellite images taken over the past 30 years to track – down to a pixel representing approximately 25 square miles – the ebb and flow of plant growth in cold areas of the northern hemisphere, such as Alaska, the Arctic region of Canada, and the Tibetan Plateau.

The 30-year historic satellite data used in the study were collected by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer. The data was processed by Boston University, and is hosted on NEX – the NASA Earth Exchange data archive.

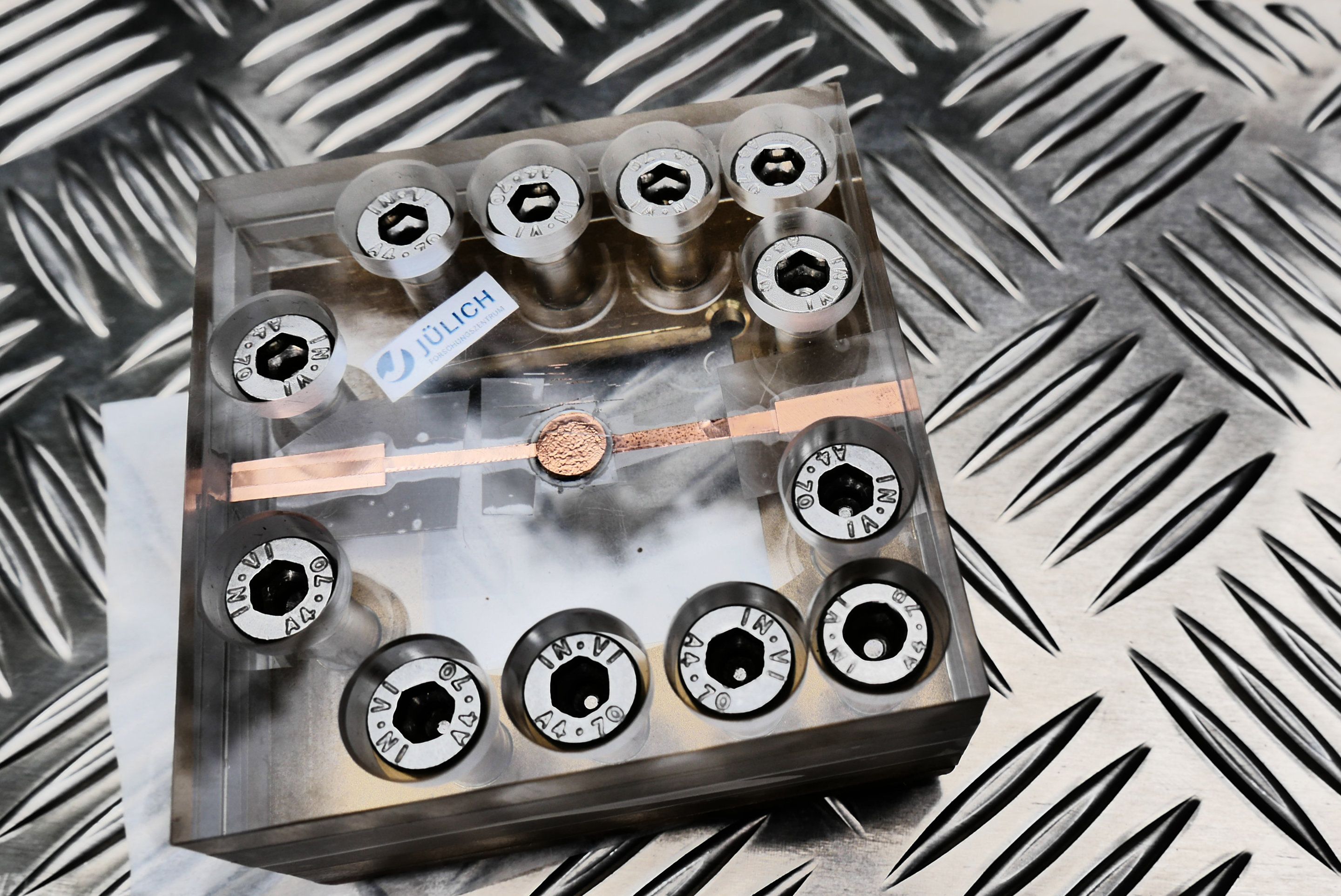

Solid-state batteries contain no liquid parts that could leak or catch fire. For this reason, they do not require cooling, and are considered to be much safer, more reliable, and longer lasting than traditional lithium-ion batteries. Juelich scientists have now introduced a new concept that allows currents up to 10 times greater during charging and discharging than previously described in the literature.

Low current is considered one of the biggest hurdles in the development of solid-state batteries because the batteries take a relatively long time to charge, usually about 10 to 12 hours in the case of a fully discharged battery. The new cell type that Jülich scientists have designed, however, takes less than an hour to recharge.

“With the concepts described to date, only very small charge and discharge currents were possible due to problems at the internal solid-state interfaces. This is where our concept based on a favourable combination of materials comes into play, and we have already patented it,” explains Dr. Hermann Tempel, group leader at the Juelich Institute for Energy and Climate Research (IEK-9).

The courts have played a central role in climate change policy, starting with a landmark Supreme Court case that led to the mandatory regulation of greenhouse gases in the United States. How do the courts address climate cases today? Who wins, who loses and what kinds of strategies make a difference in the courtroom?

Researchers at the George Washington University (GW) have published a study in Nature Climate Change that for the first time analyzes all U.S climate change lawsuits over a 26-year period.

“This first-of-a-kind study outlines the types of climate change lawsuits that are more likely to win or lose, and why,” said lead author Sabrina McCormick, Ph.D., MA, an Associate Professor of Environmental and Occupational Health at GW’s Milken Institute School of Public Health (Milken Institute SPH). “Efforts to affect U.S. climate change policy should consider current trends in the courtroom.”

Energy use in industrial buildings continues to skyrocket, contributing to the negative impact on global warming and Earth’s natural resources. An EU initiative introduced a disruptive system that’s able to reduce electricity consumption in the industrial sector.

Using energy efficiently helps industry save money, conserve resources and tackle climate change. ISO 50001 supports companies in all sectors to use energy more efficiently through the development of an energy management system. It calls on the industrial sector to integrate energy management into their overall efforts for improving quality and environmental management. Companies can perform several actions to successfully implement this new international standard, including creating policies for more efficient energy use, identifying significant areas of energy consumption and targeting reductions.

Imagine something similar to the Great Depression of 1929 hitting the world, but this time it never ends.

Economic modelling suggests this is the reality facing us if we continue emitting greenhouse gases and allowing temperatures to rise unabated.

Economists have largely underestimated the global economic damages from climate change, partly as a result of averaging these effects across countries and regions, but also because the likely behaviour of producers and consumers in a climate change future isn’t usually taken into consideration in climate modelling.

Historically, water managers throughout the thirsty state of California have relied on hydrology and water engineering—both technical necessities—as well as existing drought and flood patterns to plan for future water needs.

Now, climate change is projected to shift water supplies as winters become warmer, spring snowmelt arrives earlier, and extreme weather-related events increase. Some water utilities have started to consider these risks in their management, but many do not. Lack of climate change adaptation among water utilities can put water supplies and the people dependent on them at risk, especially in marginalized communities, a new University of California, Davis, paper suggests.

The paper, which analyzes various approaches to climate science by drinking water utility managers in California, was presented along with new research at the American Sociology Association Conference in Philadelphia on Aug. 11. The paper, “Climate Information? Embedding Climate Futures within Social Temporalities of California Water Management,” was published this spring in the journal Environmental Sociology.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=giIsJ1LhtLU

The Earth discovered it was living in a new slice of time called the Meghalayan Age in July 2018. But the announcement by the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) confused and angered scientists all around the world.

In the 21st century, it claimed, we are still officially living in the Holocene Epoch, the warm period that began 11,700 years ago after the last ice age. But not only that: within the Holocene, we are also living in this new age – the Meghalayan – and it began 4,250 years ago.

Over the past decade, more and more scientists have agreed that human impact on Earth is so significant that we have entered a completely new geological phase, called the Anthropocene, including a group convened to agree a formal definition. The world of science was expecting an official announcement acknowledging this Anthropocene Epoch, not the unheard-of Meghalayan Age. It was so unexpected it turned up zero hits on Google when first reported. So what’s going on?