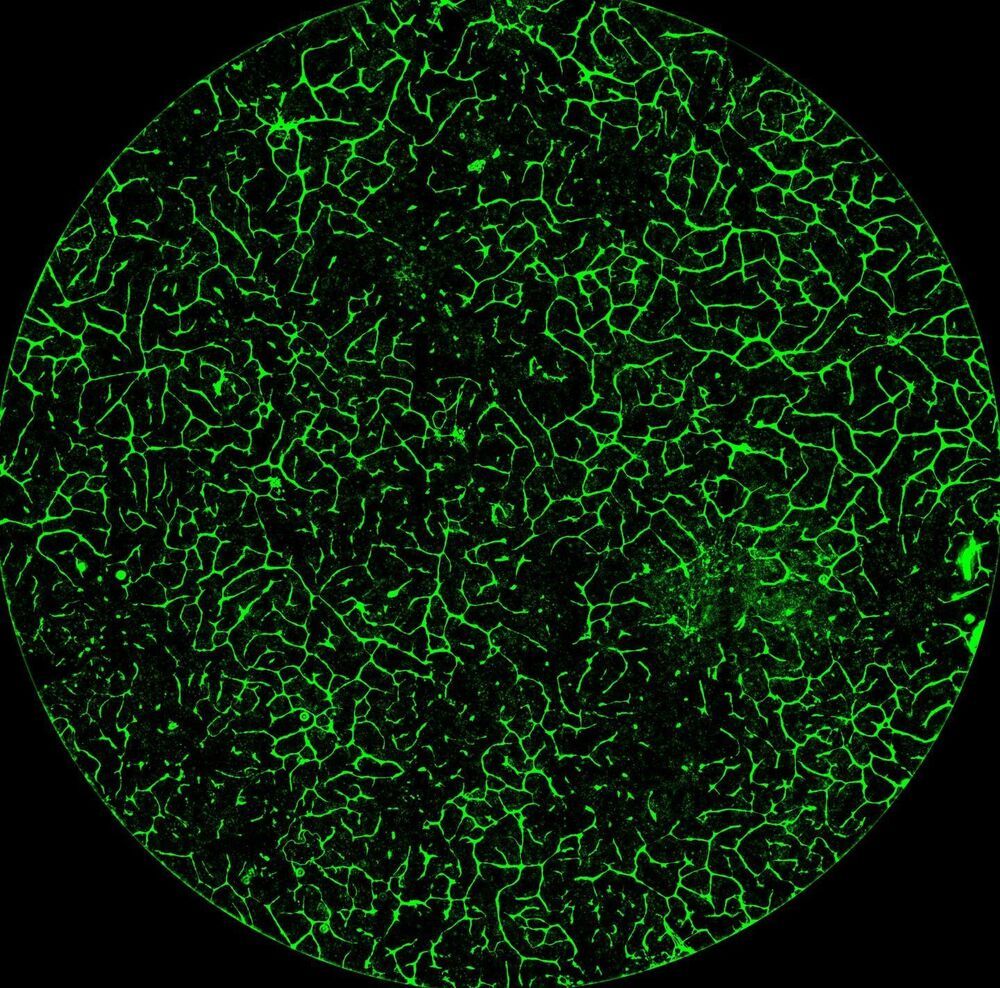

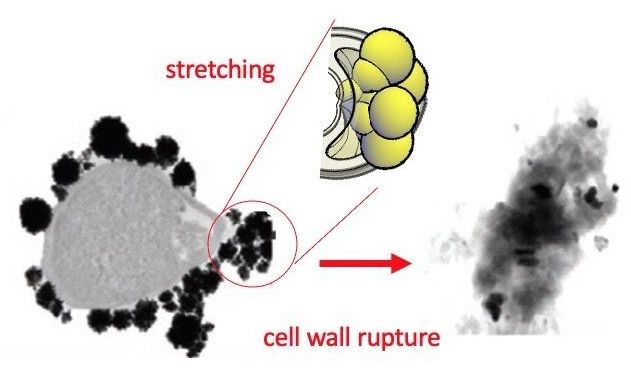

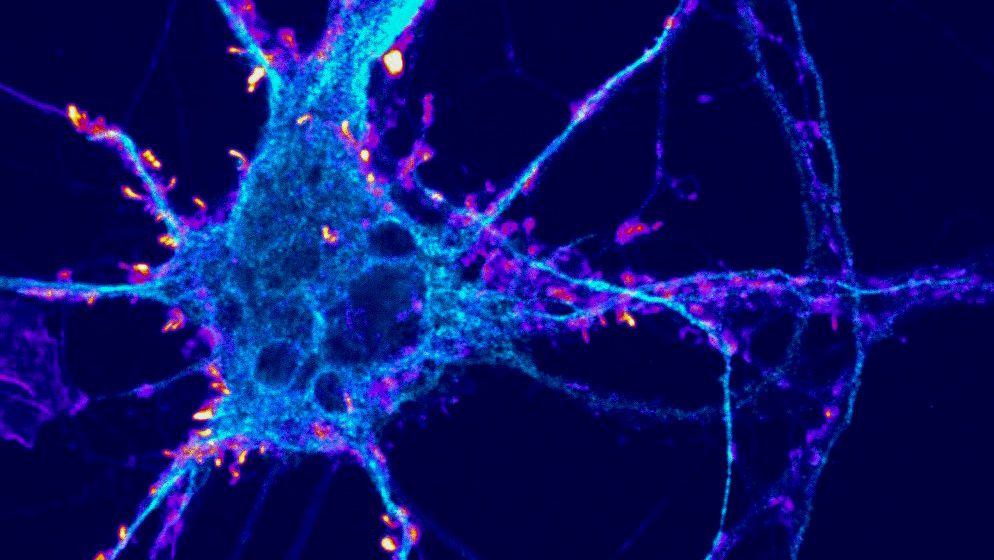

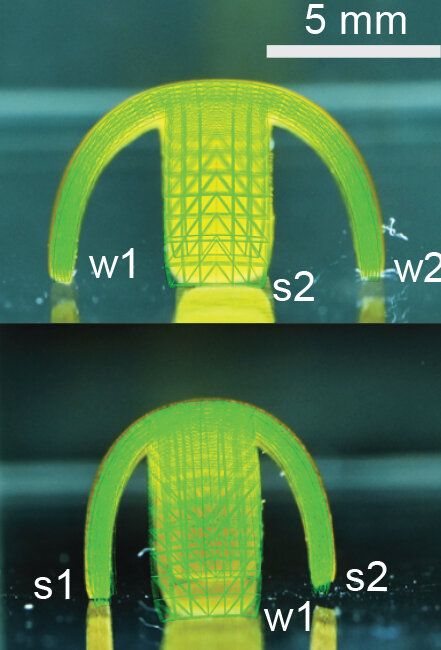

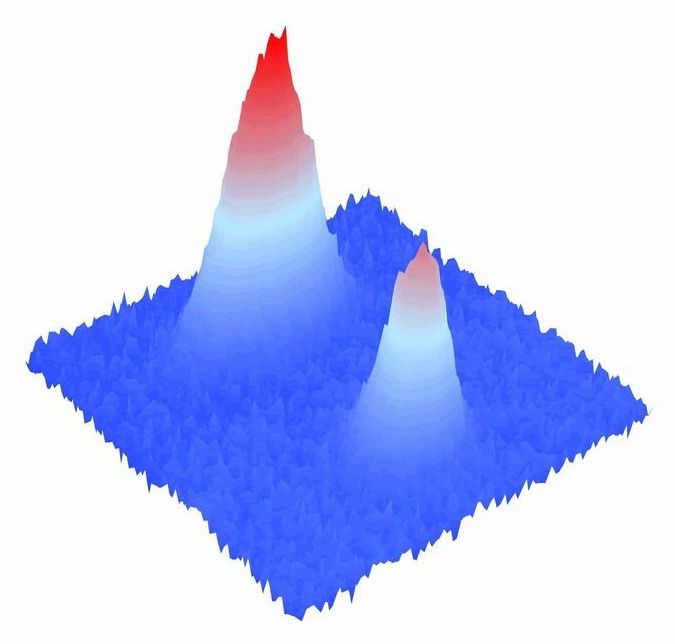

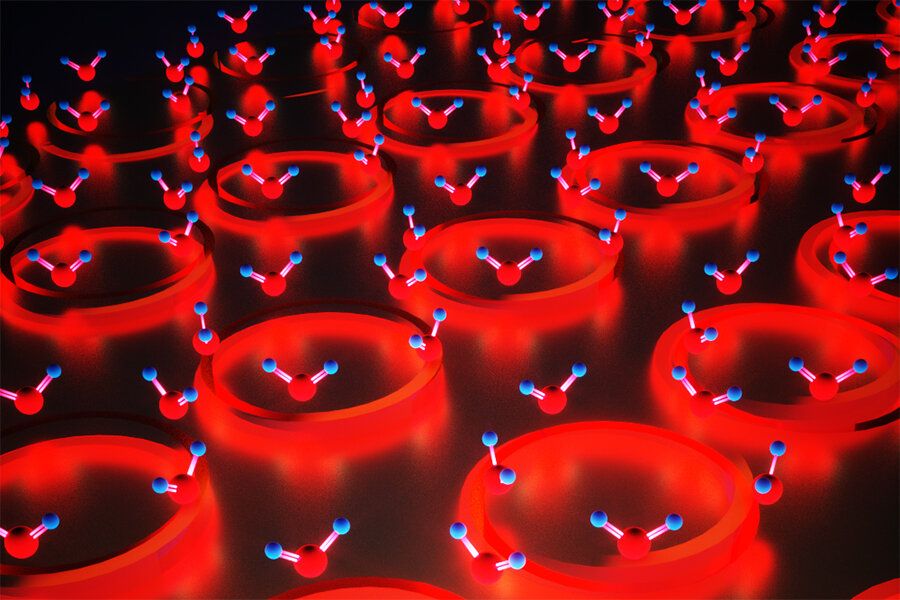

Takeaways * Scientists have made progress growing human liver in the lab. * The challenge has been to direct stems cells to grow into a mature, functioning adult organ. * This study shows that stem cells can be programmed, using genetic engineering, to grow from immature cells into mature tissue. * When a tiny lab-grown liver was transplanted into mice with liver disease, it extended the lives of the sick animals.* * *Imagine if researchers could program stem cells, which have the potential to grow into all cell types in the body, so that they could generate an entire human organ. This would allow scientists to manufacture tissues for testing drugs and reduce the demand for transplant organs by having new ones grown directly from a patient’s cells. I’m a researcher working in this new field – called synthetic biology – focused on creating new biological parts and redesigning existing biological systems. In a new paper, my colleagues and I showed progress in one of the key challenges with lab-grown organs – figuring out the genes necessary to produce the variety of mature cells needed to construct a functioning liver. Induced pluripotent stem cells, a subgroup of stem cells, are capable of producing cells that can build entire organs in the human body. But they can do this job only if they receive the right quantity of growth signals at the right time from their environment. If this happens, they eventually give rise to different cell types that can assemble and mature in the form of human organs and tissues. The tissues researchers generate from pluripotent stem cells can provide a unique source for personalized medicine from transplantation to novel drug discovery. But unfortunately, synthetic tissues from stem cells are not always suitable for transplant or drug testing because they contain unwanted cells from other tissues, or lack the tissue maturity and a complete network of blood vessels necessary for bringing oxygen and nutrients needed to nurture an organ. That is why having a framework to assess whether these lab-grown cells and tissues are doing their job, and how to make them more like human organs, is critical. Inspired by this challenge, I was determined to establish a synthetic biology method to read and write, or program, tissue development. I am trying to do this using the genetic language of stem cells, similar to what is used by nature to form human organs. Tissues and organs made by genetic designsI am a researcher specializing in synthetic biology and biological engineering at the Pittsburgh Liver Research Center and McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine, where the goals are to use engineering approaches to analyze and build novel biological systems and solve human health problems. My lab combines synthetic biology and regenerative medicine in a new field that strives to replace, regrow or repair diseased organs or tissues. I chose to focus on growing new human livers because this organ is vital for controlling most levels of chemicals – like proteins or sugar – in the blood. The liver also breaks down harmful chemicals and metabolizes many drugs in our body. But the liver tissue is also vulnerable and can be damaged and destroyed by many diseases, such as hepatitis or fatty liver disease. There is a shortage of donor organs, which limits liver transplantation. To make synthetic organs and tissues, scientists need to be able to control stem cells so that they can form into different types of cells, such as liver cells and blood vessel cells. The goal is to mature these stem cells into miniorgans, or organoids, containing blood vessels and the correct adult cell types that would be found in a natural organ. One way to orchestrate maturation of synthetic tissues is to determine the list of genes needed to induce a group of stem cells to grow, mature and evolve into a complete and functioning organ. To derive this list I worked with Patrick Cahan and Samira Kiani to first use computational analysis to identify genes involved in transforming a group of stem cells into a mature functioning liver. Then our team led by two of my students – Jeremy Velazquez and Ryan LeGraw – used genetic engineering to alter specific genes we had identified and used them to help build and mature human liver tissues from stem cells. The tissue is grown from a layer of genetically engineered stem cells in a petri dish. The function of genetic programs together with nutrients is to orchestrate formation of liver organoids over the course of 15 to 17 days. Liver in a dishI and my colleagues first compared the active genes in fetal liver organoids we had grown in the lab with those in adult human livers using a computational analysis to get a list of genes needed for driving fetal liver organoids to mature into adult organs. We then used genetic engineering to tweak genes – and the resulting proteins – that the stem cells needed to mature further toward an adult liver. In the course of about 17 days we generated tiny – several millimeters in width – but more mature liver tissues with a range of cells typically found in livers in the third trimester of human pregnancies. Like a mature human liver, these synthetic livers were able to store, synthesize and metabolize nutrients. Though our lab-grown livers were small, we are hopeful that we can scale them up in the future. While they share many similar features with adult livers, they aren’t perfect and our team still has work to do. For example, we still need to improve the capacity of the liver tissue to metabolize a variety of drugs. We also need to make it safer and more efficacious for eventual application in humans.[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]Our study demonstrates the ability of these lab livers to mature and develop a functional network of blood vessels in just two and a half weeks. We believe this approach can pave the path for the manufacture of other organs with vasculature via genetic programming. The liver organoids provide several key features of an adult human liver such as production of key blood proteins and regulation of bile – a chemical important for digestion of food. When we implanted the lab-grown liver tissues into mice suffering from liver disease, it increased the life span. We named our organoids “designer organoids,” as they are generated via a genetic design. This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. It was written by: Mo Ebrahimkhani, University of Pittsburgh. Read more: * Brain organoids help neuroscientists understand brain development, but aren’t perfect matches for real brains * Why are scientists trying to manufacture organs in space?Mo Ebrahimkhani receives funding from National Institute of Health, University of Pittsburgh and Arizona Biomedical Research Council.