👀

The GTPases constitute a very large protein family, whose members are involved in the control of cell growth, transport of molecules, synthesis of other proteins, etc. Despite the many functions of the GTPases, they follow a common cyclic pattern (Figure 1). The activity of the GTPases is regulated by factors that control their ability to bind and hydrolyse guanosine triphosphate (GTP) to guanosine diphosphate (GDP). So far, it has been the general assumption that a GTPase is active or “on” when it is bound to GTP and inactive or “off” in complex with GDP. The GTPases are therefore sometimes referred to as molecular “switches.”

The bacterial translational elongation factor EF-Tu is a GTPase, which plays a crucial role during the synthesis of proteins in bacteria, as the factor transports the amino acids that build up a cell’s proteins to the cellular protein synthesis factory, the ribosome. Previous structural studies using X-ray crystallography have shown that EF-Tu occurs in two markedly different three-dimensional shapes depending on whether the factor is “on” (i.e. bound to GTP) or “off” (i.e. bound to GDP) (Figure 2). The binding of GTP/GDP have therefore always been thought to be decisive for the factor’s structural conformation.

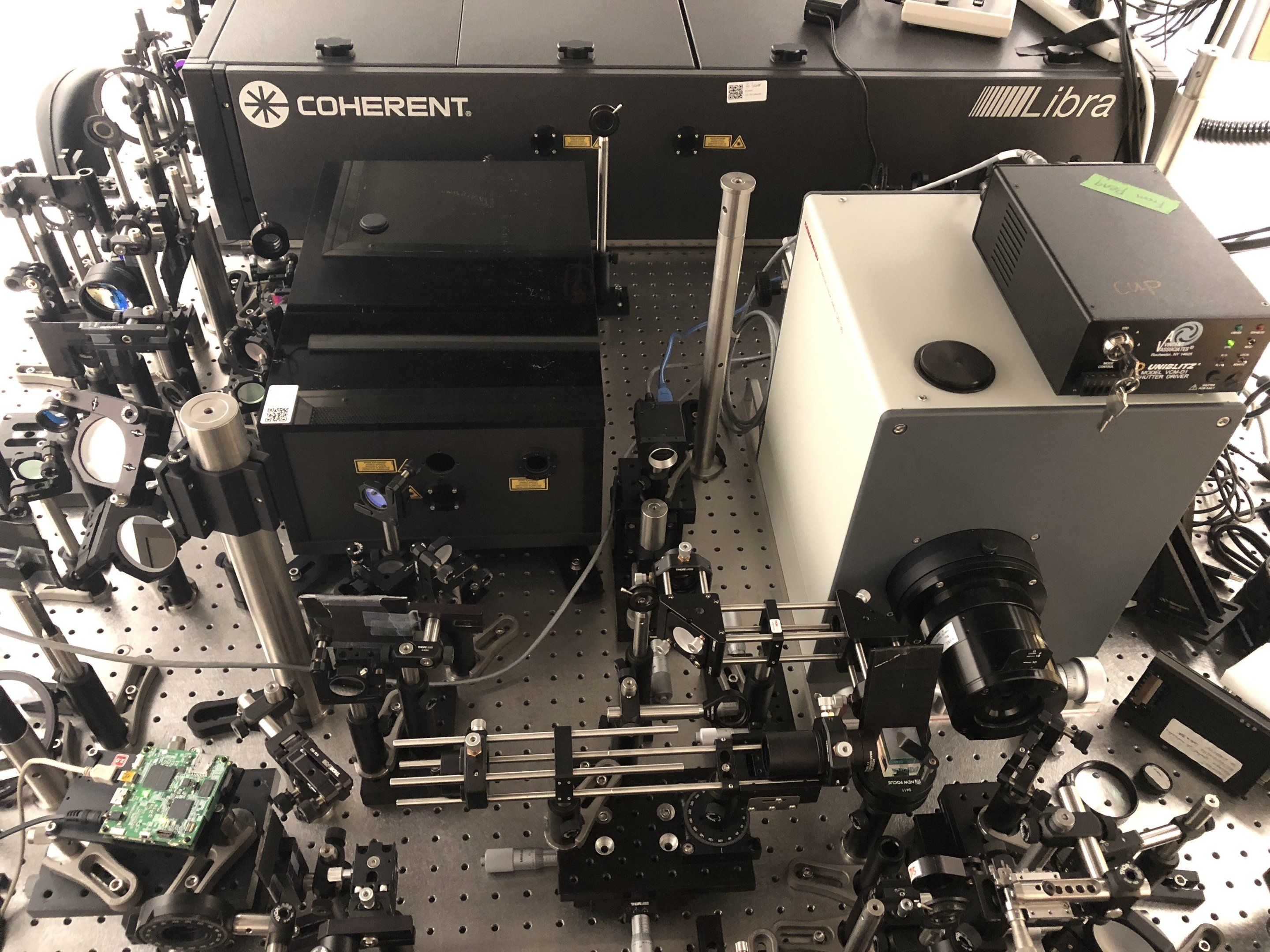

However, a research collaboration between researchers from the Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics at Aarhus University and two American universities reveals that EF-Tu’s structure and function, and probably also those of other GTPases, are far more complex than previously assumed. In Søren Thirup’s group, X-ray crystallographic analysis of E. coli EF-Tu has shown that EF-Tu bound to a variant of GTP, GDPNP, can also occur in the “off” state, which is characterised by a more open structure. In collaboration with American researchers, Charlotte Knudsen’s Ph.D. student, Darius Kavaliauskas, conducted further studies using a special form of fluorescence microscopy that makes it possible to observe the spatial structure of individual EF-Tu molecules in solution.

Read more