Thousands of

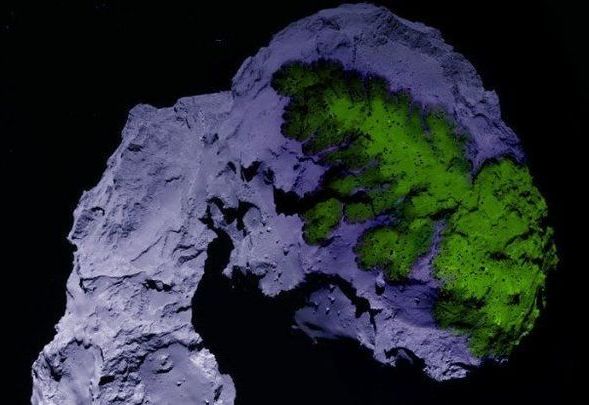

tardigrades – also known as “water bears” or “moss piglets” — were on board the

Beresheet spacecraft when it crash landed on the moon in April.

The tiny creatures are incredibly hardy and can survive extremely low temperatures and harsh conditions– and The Arch Mission Foundation, which sent them into

space, believes some may have survived.

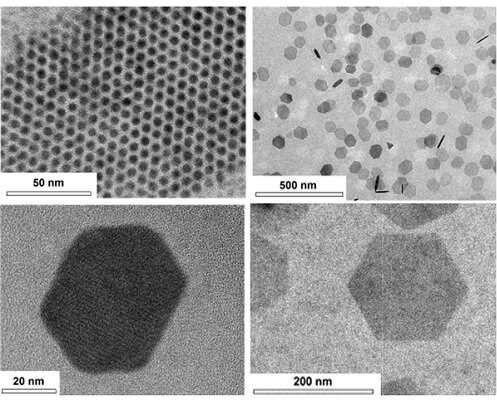

Tardigrades are pudgy little animals no longer than one millimeter. They live in water or in the film of water on plants like lichen or moss, and can be found all over the world in some of the most extreme environments, from icy mountains and polar regions to the balmy equator and the depths of the sea.

In an attempt to create a “Noah’s ark” or a “back-up” for the Earth, non-profit organization The Arch Mission sent a lunar library — a stack of DVD-sized disks that acts as an archive of 30 million pages of information about the planet — to the moon. Along with the library, Arch Mission sent human DNA samples and a payload of tardigrades, which had been dehydrated, into space.

“We chose them because they are special. They are the toughest form of life we know of. They can survive practically any planetary cataclysm. They can survive in the vacuum of space, they can survive radiation,” Nova Spivack, co-founder of the Arch Mission Foundation, told CNN.

Tardigrades have eight legs with claws at the end, a brain and central nervous system, and a sucker-like pharynx behind their mouth, which can pierce food.

The Arch Mission put the creatures into a state of “suspended animation,” where the body dries out and the metabolism slows to as little as 0.01% of its normal rate.

“In that state you can later rehydrate them in a laboratory and they will wake up and be alive again,” Spivack explained.

Although the animals won’t be able to reproduce or move around in their dehydrated state — if they have survived the crash — if rehydrated they could come back to life years later.

“We don’t often get a chance to land life on the moon that we decided to seize the day and send some along for the ride,” Spivack added.

Researchers hope that along with the tardigrades, the majority of the information from the lunar library survived the impact of the crash — and could be used to regenerate human life in millions of years.

“Best-case scenario is that the little library is fully intact, sitting on a nice sandy hillside on the moon for a billion years. In the distant future it might be recovered by our descendants or by a future form of intelligent life that might evolve long after we’re gone,” Spivack said.

“From the DNA and the cells that we included, you could clone us and regenerate the human race and other plants and animals,” he added.